“Underworld Gothic” By Dan Rabarts and Lee Murray

Lee Murray: We’ll probably shock our American colleagues by saying Halloween isn’t really a thing down here in New Zealand. No neighbourhoods of kids out Trick or Treating. No pumpkins on the doorstep. For HWA members this is akin to blasphemy. Do you think they’ll revoke our memberships?

Dan Rabarts: Well, we’re here to shock a little, aren’t we? In New Zealand we’re starting to see a bit of Trick or Treating on Halloween, but for whatever reason, it’s never really caught on. Halloween in the Southern Hemisphere comes about in late spring, so it’s not dark or cold when the kids are out, in fact it can still be sunny, which sort of distracts from the vibe that our Northern friends would normally associate with the event. For those who do get into it—having succumbed to buying up large from the Halloween costume display down at The Warehouse and who have gone out wandering the streets dressed as witches or vampires or zombies or, on the other end of the equation, having arranged a bowl of lollies near the door for those who venture as far as their front step—it’s more of an excuse to enjoy the last of the evening sunshine and not go to bed just yet. But aside from a few retailers who keep trying to convince us it’s A Thing, Halloween just isn’t. If anything, our relationship to the celebration may simply be one of quiet mockery of those who take it so seriously, those who feel a need to inject some everyday horror into their existences, because down here…? That underlying current of creeping dread is a part of life. We live on a string of major fault-lines, on the spines of any number of volcanoes, surrounded by violent and unpredictable oceans and everything they bring with them, including regular floods, cyclones and tornadoes. We live with a constant sense of isolation, both in our rural and suburban communities and even within our own neighbourhoods. We often don’t know the people who live down our street. And as for wandering around, knocking on the doors of complete strangers? This country may not have a huge problem with child abduction, but every time it happens, the media is quick to make it a major event and imprint the name and face of that missing child on the national psyche like a burning brand. No-one wants their child to be the next Carla Cardno or Kirsa Jensen.

Lee: Yup, way down here at the bottom of the world gothic horror is as pervasive as sheep dung. And equally dark. Almost all of our iconic texts can be categorised as gothic: writers like Katherine Mansfield, James K Baxter, Janet Frame, authors whose work is set in bleak, lonely, threatening landscapes, in small isolated communities, and where the characters are wild, unexpected, extreme. I suppose it’s not that surprising. New Zealand, in its early days, was a hostile place. Uneasy. You needed a certain resilience to survive here.

Dan: We’re a young country, that’s for sure. Even our Māori history can be counted in mere centuries, as opposed to the thousands of years that most the rest of the world has to draw on. So there’s a lot of unknown in the mix, a lot of the unexplored, the undeveloped. The inaccessible. We have a lot of roads to nowhere, dark regions of the interior which simply cannot be reached. And we choose to build our lives around these places, at the ends of dirt roads, along coastlines of jagged cliffs, turning to stare into the shadows of forests that have stood sentinel over the untouchable places for longer than people have been here. It’s no wonder we look at our bush and back country with fear and trepidation, despite the lack of lions and tigers and bears. In the grand scheme of things, against the backdrop of the millions of years that Aotearoa has laid out here in the grip of the South Pacific, we are intruders. Invaders.

Lee: For a while, there was this idea that our Kiwi gothic tradition was in response to a Pākehā (white) experience of New Zealand.

Dan: Perhaps, but the gothic in Aotearoa goes back further than just European influence, much further even than HP using Dunedin as a setting in Call of Cthulhu. The Māori storytelling tradition was primarily oral, combined with whakairo (the art of carving histories and narratives into the structure of wharenui and other significant buildings), and those stories could be extremely dark, if you look hard enough to find the origins of these narratives and not the sterilised versions they tried to teach us in primary school. Even the fundamental creation myths of Māori legend are brutal. Maui, our trickster godling-hero, hooks up a fish from the sea and butchers it alive, to form Te Ika a Maui, A.K.A the North Island, upon whose petrified carcass Lee and I both live. When Ra, the sun, travels across the sky too fast for anyone to get any work done, Maui and his brothers fashion a net to catch it where it rises from its hole in the ground, and then beat it into submission with their mere and patu, until it agrees to travel more slowly, and to this day we sometimes see the ropes from that mighty net, falling down between the clouds, reminding us that with violence and determination we can even defeat the power of the sun.

Lee: Exactly. In his book Mapping the Godzone (1998) American William Schafer highlighted the significance of Māori mythology and culture in the development of our Aotearoa gothic:

“A common cultural link between Pākehā and Māori is a belief in the hauntedness of the landscape, the sense that Aotearoa New Zealand is a land of sinister and unseen forces, of imminent (and immanent) threat, of the undead or revenant spirits.”

Dan: True. Our gods and ghosts are primeval, a constant presence in the backs of our minds, both bloodthirsty and mischievous. Turn your back, deny them for even a moment, and they don’t miss an opportunity to remind us they’re there, and that they don’t like us. New Zealand is full of ghosts, all the time, not just on Halloween.

Lee: And there’s that sense that our ghosts, our wairua-spirits, exist close to the surface. Here in New Zealand, we exist on the edge of the underworld.

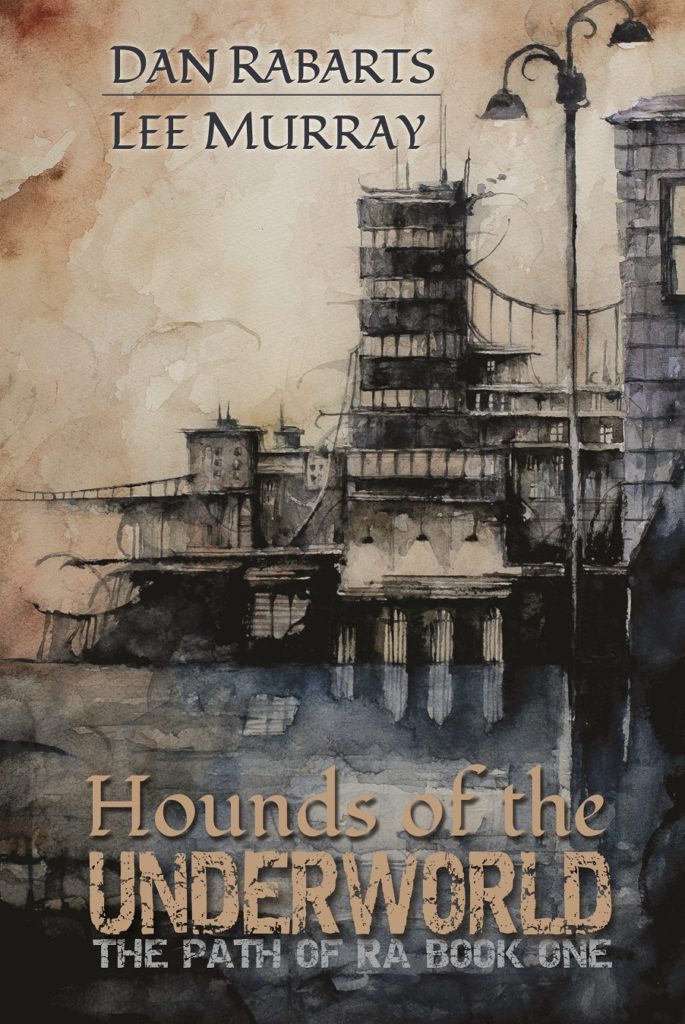

Dan: This is something we set out to capture when writing Hounds of the Underworld, the sense of something else beyond the veil, just the other side of where we live. Matiu frequently touches on this other world:

“It washes over Matiu, a cold dread whisper, a rasping of sand across barren places, a swaying of his senses, broken blades of sound stabbing through him from somewhere beyond the veil.”

And in case you were wondering, there’s nothing friendly over there.

Lee: In Hounds of the Underworld, my character, Penny, is the ultimate denier with her starched white lab coat and her insistence on scientific rigour. In a way, she represents our indomitable Kiwi stoicism when faced with everyday all-consuming menace, the ‘she’ll be right’ attitude that is part of our make-up. We don’t celebrate Halloween down here in New Zealand because there’s simply there’s no need. Here, departed souls hunker on our doorsteps, the earth rumbles and shakes while our gods squabble—even the wind seduces us with the patu-paiarehe’s trickery. In Aotearoa, all we need do is step outside.

TODAY’S GIVEAWAY: Dan Rabarts and Lee Murray are giving away a copy of their supernatural crime-noir title Hounds of the Underworld (print or ebook, depending on the winner’s preference). Comment below or email membership@horror.org with the subject title HH Contest Entry for a chance to win.

Dan Rabarts is an award-winning short fiction author and editor, recipient of New Zealand’s Sir Julius Vogel Award for Best New Talent in 2014, and the Paul Haines Award for Long Fiction as part of the Australian Shadows Awards in 2017. His science fiction, dark fantasy and horror short stories have been published in numerous venues around the world, including Beneath Ceaseless Skies, The Mammoth Book of Dieselpunk, and StarShipSofa. Together with Lee Murray, he co-edited the anthologies Baby Teeth – Bite-sized Tales of Terror, winner of the 2014 SJV for Best Collected Work and the 2014 Australian Shadows Award for Best Edited Work, and At the Edge, a collection of Antipodean dark fiction. Find out more at dan.rabarts.com.

Lee Murray is a multi-award-winning writer and editor of fantasy, science fiction, and horror, including the bestselling Into the Mist (Cohesion Press), which World Horror Master Michael B. Collings described as “adrenalin-fueled excitement in a single, coherent, highly imaginative and ultimately impressive narrative”. She is proud to have co-edited six anthologies of speculative fiction, one of which won her an Australian Shadows Award for Best Edited Work (with Dan Rabarts) in 2014. Her latest title, Hounds of the Underworld, is a supernatural crime-noir written in collaboration with Dan Rabarts and published by Raw Dog Screaming Press. Lee lives with her family in the Land of the Long White Cloud, where she conjures up stories for readers of all ages from her office on the porch. www.leemurray.info

Book links:

Available from Amazon, bookstores, or direct from the publisher.

Blurb:

On the verge of losing her laboratory, her savings, and all respect for herself, Pandora (Penny) Yee lands her first contract as scientific consult to the police department. And with seventeen murder cases on the go, the surly inspector is happy to leave her to it. Only she’s going to need to get around, and that means her slightly unhinged adopted brother, Matiu, will be doing the driving. But something about the case spooks Matiu, something other than the lack of a body in the congealing pool of blood in the locked room or that odd little bowl.

Matiu doesn’t like anything about this case, from the voices that screamed at him when he touched that bowl, to the way his hateful imaginary friend Makere has come back to torment him, to the fact that the victim seems to be tied up with a man from Matiu’s past, a man who takes pleasure in watching dogs tear each other to pieces for profit and entertainment.

Hounds of the Underworld blends mystery, near-future noir and horror. Set in New Zealand it’s the product of a collaboration by two Kiwi authors, one with Chinese heritage and the other Māori. This debut book in The Path of Ra series offers compelling new voices and an exotic perspective on the detective drama.

Praise for Hounds of the Underworld:

“Written with verve, Rabarts and Murray’s novel has as much heart as suspense.” —Publishers Weekly

“…a wild and gruesome treat, packed with mystery, action, and dark humor. Horror fans will devour it!” —Jeff Strand, author of Wolf Hunt

“Filled with an incredible unity of voice and magnificent world building, Hounds of the Underworld was impossible to put down. I was hooked on the first page.” —Jake Bible, Bram Stoker Award-nominated novelist and author of Z-Burbia, Mega and Salvage Merc One

“A dark tech-noir so near to our future, it could be tomorrow, hard-boiled and hair-raising! One of the best speculative fiction novels ever written.” —Paul Mannering, Engines of Empathy

Read an excerpt from Hounds of the Underworld, by Dan Rabarts and Lee Murray

The place smells wrong. Not even bad, nothing Matiu can put his finger on. Just plain wrong, yet also, inexplicably, quite perfect. Spread out before him in shades of blood and bone he can see the shape of human history to come. Gradual decay and violent collapse all rolled into one brutal augury which he, for all his cursed vision, is too blind to comprehend. Like rot and sand and despair, and this stink of death just a distraction. An afterthought.

Moving away from the babble of voices—his sister, the detective, the uniform, the real estate agent who found the remains—Matiu walks a long slow arc around the mess in the middle of the room, hemmed in by its sagging border of yellow crime scene tape. In some places, the tape droops into the muck, the edges turning up in the draught. Like something out of a B-grade horror flick.

It’s not his business, nothing the fuck to do with him. He’s just a driver, the moody Māori with the ink on his cheek, his nose, his chin, drawing those mildly suspicious glances from the cops. Wouldn’t even be allowed in here if Penny wasn’t the consult, if he wasn’t her de-facto bodyguard.

But he can’t look away. They’re convinced someone died here, because there’s a puddle like someone dumped a barrel of offal and rotten vegetables soaked in red wine across the floor. But try as he might, Matiu just can’t see a body in the muck. The only thing in there he can recognise is the bowl. It’s one of those carved wooden pieces of junk they sell at the Pasifika markets over in Manukau, soft light wood with figures carved on the sides and detailed in black ink, trying to make itself look all authentic as if it actually came from the islands, and wasn’t just churned out in some South Auckland garage by kids whose parents should be sending them to school but are sweatshopping them instead. The bowl sits there in the muck, soaked in red, rivulets of dried blood clinging to its sides like spider webs. Like some fool thought they could catch all that mess in a goddamned fruit bowl.

“Bet they got a shock,” Matiu mutters. He kneels near the crime tape, drags a finger through the congealed blood, sniffs it. Wrinkles his nose. He doesn’t know what a dead body should smell like; meat and shit and stale blood, probably. This is all that, and something else. Something sweet, fruity. Almond? Something he really doesn’t want to put his nose into any further, in any sense of the word. He rubs his fingers together, feels grit on his skin. Dirt, maybe, or sand, in the old blood.

He stands, wiping his hand on his coat, looks about. The rest of the building was pretty clean, swept and vacuumed and ready for potential buyers. Until the real estate agent had forced the locked door, thinking it was stuck. She’d entered the room and found the pool of gore; stepped into the scene of a murder, maybe, or something worse.

Interesting shit.

But it’s not any of his fucking business.

His eyes fall on the bowl. It’s inside the tape, not far, but further than he can reach. He’ll have to step over if he wants to touch it.

None of your fucking business.

That would really piss off his sister. Penny gets funny about shit like disturbing the scene of a crime. But the bowl knows. It’s the thing that doesn’t belong. Hell, none of it belongs, not the cold spill of mortal remains, not the blood-spattered crime tape, not the creeping sense that something happened here, something more than just someone dying, someone being blended to a sludge, something rank and corrupt. It’s the bowl.

“Go get it.”

“Piss off,” he replies to the shadows, to the voice at his shoulder.

But he knows he will.

Excellent article with some very interesting points raised about our (New Zealand) propensity to engage with the dark stuff.

An utterly fascinating post. Makes me want to dig in more to Maori mythology.

Thanks for sharing!