And the Clock Strikes Three AM: Time and Timing in Terror, the Sequel

Last month’s terror-time about time-and-terror was firmly grounded in reality—creating timetables that work inside the book (natural character reactions to stimuli and logical story flow) and inside the reader’s mind (pacing appropriate for the specific audience’s needs, and avoiding shattering suspension of disbelief through overuse of techniques that, when used sparingly, should enhance tension). Immersion was the name of the game, with an end goal of a truer feeling story and the horror that relating to it as true-ish brings.

Last month’s terror-time about time-and-terror was firmly grounded in reality—creating timetables that work inside the book (natural character reactions to stimuli and logical story flow) and inside the reader’s mind (pacing appropriate for the specific audience’s needs, and avoiding shattering suspension of disbelief through overuse of techniques that, when used sparingly, should enhance tension). Immersion was the name of the game, with an end goal of a truer feeling story and the horror that relating to it as true-ish brings.

But before you go off and wed your story to reality at the altar of believability, there’s another variable. Unless you’re writing true crime or some other form of potentially scary nonfiction, what you’re writing isn’t real. To make it feel real enough to evoke the unconscious physical signs of horror—goosebumps and chills—and to take root in your reader’s mind to (pleasurably) torment her for years to come, you don’t need to toss aside all conventions of fictional narratives.

Rather, by taking some of the most criticized work of the founder of analytical psychology, Carl Jung, and bastardizing it to fit our needs, we can bridge the gap between reality and narrative symbols in a way that allows the fiction to leak into reality better, shaking the reader’s faith in his safety.

Carl Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious is complicated and German; boiled down to what’s germane to horror writers, it describes an unconsciousness shared by all of humanity that includes archetypes and symbols and without any actual source for individuals, but rather a universal heritage of humanity. If we save time by tossing out the nuance, we can distill this into a narrative tool.

The mystical spin that prevents scientific examination of this idea gives symbols supernatural weight in the real world. As for more realistic horror stories, the psychological aspects of this theory provide frameworks for the minds of our strictly-human monsters, their violent drives, and their inhuman, illogical crimes.

With time’s long-held relationship with reality and madness, already there’s a wonderful garden of time superstitions and symbols ripe for the plucking. You have the witching hour (once referred to 3:00 am, now colloquially means midnight), the devil’s hour (3:00 am retained at least one jinxed name), unlucky 13—and those are just some of the most famous. When you name the moment, you give it symbolic weight—either as something meaningful in the agenda of your human villain, or through its direct relationship with the supernatural powers harassing your protagonist.

Supernaturally, the symbolic time functions as part of the rules of the unnatural threat—new rules, superseding the understood rules of reality (and the rules of reality are what give the safe distance between reader and story). By forcing the reader to confront this, it also opens the reader to the possibility that the laws governing the nature of reality might not be as stable as he would like. It’s too far out there for readers to believe it hook-line-and-sinker, but it’s a tool that can be used as one of the supports for suspension of disbelief and story immersion, and it thematically seeds the kind of thoughts that keep the “what if” of horror in the reader’s mind long after the last page is turned.

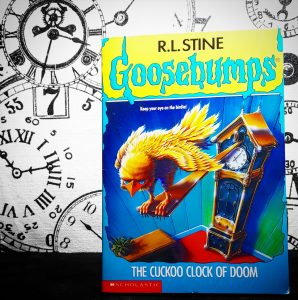

While virtually any symbol can be trumped up like this using the collective unconsciousness, time is an especially useful class when crafting horror explicitly for younger audiences. The lack of agency in your young reader’s daily life—the inability to set one’s own schedule—gives the clock a heavier weight in the nonfictional narrative of the reader’s own life. The parent choosing the time the child must wake, the legal threat of truancy laws, bathroom breaks only at predetermined blocks of time, tests with time limits, legal curfews—for kids, time functions as an externally imposed, immovable force that controls them and their lives.

Take the solidity of time as a hard construct controlled by others (adults), and then add to that the young reader’s developing perception of time (waiting for a turn on an amusement park ride takes eons; once on the ride it is over in a blink and a sneeze). This perception is further complicated by how little time they’ve experienced: a twelve-year-old has existed for 144 months—if those last three months were summer, then that single summer made up 2% of her life. Childhood amnesia starts kicking in at age 7—conservatively cut the 144 months in half and the 12th summer doubles to a significant 4% of remembered life.

As a related side note, if the above math makes you uncomfortable, interpret this as another bonus of time in horror, for its numerals. If you like math, then consider breaking time to break what should be dependable and logical, to destabilize your character and reader alike. Here’s where your missing time, and impossible or inconsistent timelines, come into play—destroying trust in what should be a factual constant.

To get back to the point, young readers experience time with more weight due to the aforementioned external force-ishness of it (being handed down by the adult world), and due to a smaller amount of context born from experience of it. This makes them, as a group, extra susceptible to time-based symbolism. Where we break from the collective unconscious theory, however, is we’re going to interrogate where the source of the symbol’s meaning, both supernaturally sourced (as discussed previously) or when given an external-physical treatment: à la something that is time sensitive, the deadline with extra stress on the dead.

The symbolic weight comes from the solid consequences, and it manifests in things like the amount of time protagonists must survive before rescue can arrive, a deadly curse or disease that must be broken or cured in time, or a supernatural or human ghoul’s schedule of operations. You name the time to invoke the dread, give shape to the concept. Don’t overuse this as a gimmick (or dodge following through with consequences for characters who fail to meet their deadlines), and you’ll be just fine.

There’s obviously no set of rules governing the best or only ways to use time and timing in the service of terror. After all, if there were then soon everyone would be using time only in those ways, and they would become a predictable formula—and predictable is the enemy of scary. But writers should take the time to think through the different manifestations of time—from punctuating their jump scares to avoid training readers to expect them, all the way to supernatural encroachment and the new rules of reality it brings, and everything in between.

Savvy writers will find that this mundane, inescapable aspect of reality can both give their story (and character’s actions) credibility while easily becoming a manifestation of something else inescapable, something much more sinister.

Mac Childs is a book reviewer, academic critic, and bookseller who has published (and buried) horror short stories under a different name. Mac first came to horror through the ancient art of “Making up stories for the sole purpose of tormenting younger siblings and giving them nightmares.” Mac’s favorite children’s horror tale is Goosebumps #43: Beast from the East by R. L. Stine.

Mac Childs is a book reviewer, academic critic, and bookseller who has published (and buried) horror short stories under a different name. Mac first came to horror through the ancient art of “Making up stories for the sole purpose of tormenting younger siblings and giving them nightmares.” Mac’s favorite children’s horror tale is Goosebumps #43: Beast from the East by R. L. Stine.