Surviving Records: Found Footage in Print

Shaky camcorders, baby monitors picking up paranormal activity, mysteriously unearthed videos—it’s no wonder found footage flourishes so well in cinematic horror. It’s visually compelling metafiction that doesn’t undermine audience immersion.

Shaky camcorders, baby monitors picking up paranormal activity, mysteriously unearthed videos—it’s no wonder found footage flourishes so well in cinematic horror. It’s visually compelling metafiction that doesn’t undermine audience immersion.

It can be a little harder to pull off in print (especially because the author name on the physical book is rarely also the name of a character inside of it, a limitation The Blair Witch Project marketing team didn’t face when they released fake missing posters of their leads and even convinced some that the actors were dead). But, it can still be a lot of fun and provides many options.

When applying found footage to text, you can either write it into a story (à la a protagonist discovering some form of footage), or write the footage as the story.

Writing found footage into a story

Writing it into a story is pretty easy, but has one major pitfall. Usually, a character with some kind of found footage is also experiencing creepy things that parallel the documented horrors. Sometimes, the authors give too many mystery answers to their character too soon, and so needs reasons for the character not to examine the found footage.

The character will have the whole record, but will be too “busy” or “distracted” to read or watch the mysterious materials (or even worse will have “forgotten” about it, because readers won’t have), or will constantly be interrupted every time they try to look at it.

This frustrates readers, who inevitably are more invested in the answers in the footage over whatever subplot pulls the character away. It draws attention to the fact that the author is deliberately concealing information, forcing the character to behave in unnatural ways, so as to later deploy revelations at a time better for the purposes of the plot. Drawing attention to the plot mechanisms is the wrong kind of metafiction to go for in found footage!

To get around this, authors can either give the footage to the protagonist piecemeal, or give the character a compelling reason why they aren’t diving into it for answers.

Parts of the footage could be damaged, or not make enough sense (yet) for the character (and reader) to work through it.

Or, there could be some kind of emotional pain preventing the character from reading it—e.g., the protagonist struggles to read her long-lost favorite aunt’s diary because the aunt’s words reopen old grief wounds. In that case, you’d better write your character’s pain viscerally enough that readers will side with your character.

Or, you could give the character a reason to fear learning the found footage contents. Ideally, through the character’s visceral reactions, you could cultivate enough sympathetic fear that the reader will dread learning what the footage contains (in the way someone afraid of horror movies will say they can’t watch, but then peek through fingers anyway so as not to miss a bit).

The reason the character hasn’t memorized this highly-applicable-to-their-own-conflict material isn’t a set-it-and-forget-it excuse. It needs to be strategically mined for tension, and something the character actively struggles with in order for it to have maximum impact, and for that final reveal to land where it needs to.

The text as found footage

The other way to do found footage in print is if the book itself is the found footage. The direct way of doing this is a character’s purposeful writing, be it in epistolary or diary form (like in Megan Crewe’s The Way We Fall, about an isolated island and a virus).

To make the direct-from-protagonist method work, again, it all comes down to character. Keep it rooted in the writing character’s emotions and viewpoint, as any time plot forces words or actions unnatural to the character, you’ve lost all metafictive edge and undermined your tension.

The other way of doing the book as found footage uses distance. In the distance way, the narrator is merely the character—in the story’s universe and possibly implied to be a real person (à la Lemony Snicket)—who has collected the pieces of the story and is sharing them.

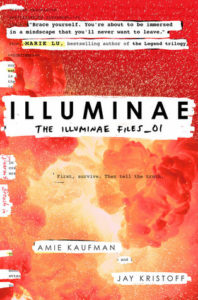

A really great recent example of this at work is in the Illuminae series by Amie  Kaufman and Jay Kristoff. The conceit of the series is that the books are files salvaged from a disaster to explain exactly what happened and how it went so wrong.

Kaufman and Jay Kristoff. The conceit of the series is that the books are files salvaged from a disaster to explain exactly what happened and how it went so wrong.

The reason Iluminae works so well is because it is fully committed to its premise. The authors took pains to preemptively address immersion-challenging questions that readers would ask (such as: where did these files come from? why do the people making the files care about the relationship status of teenage exes?). What worked well in this case was that the answers to such questions and more were framed as the document assemblers justifying their inclusions and citing sources for the mysterious client that commissioned the files—plausible, considering the amount of fictional money on the line for the assemblers’ accuracy and completion.

The lesson to take away is to figure out all of the questions readers will have, and also to figure out who in the story would also have those questions, and how those characters would go about getting their answers. For distanced found footage in text, the margin of error for ruining immersion by drawing attention to the book as a fictional construct is razor thin. This is not the time for in-jokes or shortcuts; it’s time for as much scrutiny as humanly possible.

On immersion

After all, in a found footage movie the audience has more than the story writer to rely on—the actors, sound cues, lighting, art direction, and more all work together to convince the movie-goers that it is real (even as they know it isn’t). For a writer of a found footage book, the only help for immersion comes from your own reader’s brain.

Your reader must want to believe in the story you are presenting (even as they know it’s fiction). If you give readers too much to hand-wave away, put too much of the immersive onus on them, you’ll lose them no matter how compelling the other elements of your story are.

Found footage is a powerful technique, and one that can be just as exciting in print as in any movie. So, use it wisely, and make sure it’s always thought-out. And if at first you don’t succeed? You may temporarily lose your footage, but once you find it again you’ll be well rewarded.

Mac Childs is a book reviewer, academic critic, sometimes-bookseller, and sometimes-librarian who has published (and buried) horror short stories under a different name. Mac first came to horror through the ancient art of “Making up stories for the sole purpose of tormenting younger siblings and giving them nightmares.” Mac’s favorite children’s horror tale is Goosebumps #43: Beast from the East by R. L. Stine.

Mac Childs is a book reviewer, academic critic, sometimes-bookseller, and sometimes-librarian who has published (and buried) horror short stories under a different name. Mac first came to horror through the ancient art of “Making up stories for the sole purpose of tormenting younger siblings and giving them nightmares.” Mac’s favorite children’s horror tale is Goosebumps #43: Beast from the East by R. L. Stine.