Halloween Haunts: Weird Women Take on Halloween: Five Early Halloween Works by Women by Lisa Morton

When we remember holiday ghost tales, we probably go to Charles Dickens and the most famous ghost story of them all, “A Christmas Carol”. Think about Halloween stories, and you might imagine that you’d have to wait until at least the mid-twentieth century, when Robert Bloch and Ray Bradbury rolled around.

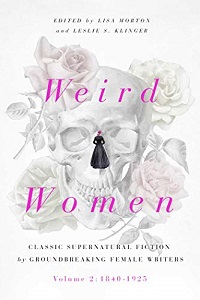

But here’s one of those historical bits that even the most knowledgeable horror fan might have missed: many of the earliest stories about Halloween were by women. That’s right, not long after Dickens tormented Scrooge with Christmas ghosts, his feminine counterparts were setting their spirits loose on Halloween. After co-editing (with Leslie S. Klinger) four volumes of classic horror fiction – Ghost Stories: Classic Tales of Horror and Suspense, Weird Women: Classic Supernatural Fiction by Groundbreaking Female Writers 1852-1923, Weird Women 2: Classic Supernatural Fiction by Groundbreaking Female Writers 1840-1925, and (coming in 2022), Haunted Tales: Classic Stories of Horror and Suspense – I’m pleased to have discovered that my early sisters were sharing my love for our favorite holiday.

Here are five great works about Halloween by women, presented in chronological order:

“Hallowe’en” (1870) by Helen Elliott – This story first appeared in Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine, which was obviously intended for a female audience. Elliott was not a major literary figure – I couldn’t find out anything else about her – but this is a charming story that combines Scottish-Irish Halloween traditions (fortune-telling, games, ghost stories) with light supernatural content (fortunes told and dreams come true), and a post-Civil War love story. The first few pages of the story are a detailed description of a Halloween party employing such rituals as burning nuts in a hearth, the Luggie bowls (three bowls containing different materials; whichever was chosen by a blindfolded participant would indicate their future), and making dumb cakes, small cakes made in silence that would supposedly be eaten only by one’s future spouse. When young Nell’s fiancé Ned goes missing in the Civil War, she fears the worst…but the story ends up using a final Halloween fortune-telling game (involving throwing out a ball of yarn) to provide a happy ending. This piece undoubtedly inspired women all over America to host their own Halloween parties. Here’s an excerpt that describes a Halloween game of the past that would never fly in the 21st century:

Now for “Snap-dragon.” Nell brings in a platter heaped up with raisins. She pours some alcohol on them, and sets it on fire. As soon as it burns well, the girls snatch at the raisins, whirling the little fire-balls through the air; and, when they fall, scrambling for them, not caring in the least for their having been on the floor. Nell watches this game anxiously, and is rather glad when it is concluded.

“Man-Size in Marble” (1887) by Edith Nesbit – Edith Nesbit is now most well-known for her children’s books – especially The Railway Children – but she was also a gifted horror author whose 1893 collection Grim Tales includes this one as well as other gems like “John Charrington’s Wedding”. Based on local legends, this classic is both one of the most chilling ghost stories ever written and an early Halloween classic that deserves re-reading every October. It tells the story of a young married couple who have moved into a house in a small village that trembles with dread every Halloween, when it’s believed that two marble effigies in the local church rise to walk the streets. Here’s an excerpt in which the young couple’s hired maid gives them the back-story:

“They do say, as on All Saints’ Eve them two bodies sits up on their slabs, and gets off of them, and then walks down the aisle, in their marble”—(another good phrase, Mrs. Dorman)—”and as the church clock strikes eleven they walks out of the church door, and over the graves, and along the bier-balk, and if it’s a wet night there’s the marks of their feet in the morning.”

“And where do they go?” I asked, rather fascinated.

“They comes back here to their home, sir, and if any one meets them—”

“Well, what then?” I asked.

But no—not another word could I get from her, save that her niece was ill and she must go. After what I had heard I scorned to discuss the niece, and tried to get from Mrs. Dorman more details of the legend. I could get nothing but warnings.

“Whatever you do, sir, lock the door early on All Saints’ Eve, and make the cross-sign over the doorstep and on the windows.”

Hallowe’en: How to Celebrate It (1898) by Martha Russel Orne – Okay, I’m cheating a bit here because this is non-fiction, but it’s worth mentioning because of its historical significance (it was the first book dedicated solely to Halloween), its precedence (most of the major Halloween histories that would follow were also by women), and its charm. The book is 48 pages long and focuses mainly on staging Halloween parties, but it does open with a nicely-written (if only partly accurate) look at Halloween’s history, including this evocative paragraph:

As the Druidic faith faded in the light of Christianity, the heathen festivals lost much of their grandeur and former significance, and assumed a lower character. Gradually the simple country folk came to believe that on October 31st the fairies forsook their hiding-places to dance in the forest glades, while witches, goblins, and other evil spirits held revels in deserted abbeys, or plotted against mankind in the shadows of ruinous castles and keeps.

“Marsyas in Flanders” (1900) by Vernon Lee – Vernon Lee is the pseudonym of Violet Paget, a writer now equally admired for both her work and her adventurous lifestyle. Lee was an ardent feminist, a pacifist (during World War One), a friend of the great painter John Singer Sargent, whose portrait of her is well known, and she had close longstanding relationships with several women, although scholars debate her sexuality. Her supernatural fiction is now among the most highly regarded produced by turn-of-the-century authors, often centering the horrors around works of art. In “Marsyas in Flanders”, a researcher has come to a small coastal town to study a famous statue in the local church, supposedly showing Christ on the cross…but the researcher uncovers a far more sinister identity to the statue’s subject. Here’s the Halloween part of the history the researcher uncovers (keep in mind that “the Vigil of All Saints” is another name for Halloween):

For, on the Vigil of All Saints, 1299, the church was struck by lightning. The new warder was found dead in the middle of the nave, the cross broken in two; and oh, horror! the Effigy was missing. The indescribable fear which overcame everyone was merely increased by the discovery of the Effigy lying behind the high altar, in an attitude of frightful convulsion, and, it was whispered, blackened by lightning.

“The Banshee’s Halloween” (1903) by Herminie Templeton Kavanagh – Now best known for creating the character of Darby O’Gill, who would become the title subject of the 1959 Disney film Darby O’Gill and the Little People, Kavanagh was a gifted storyteller who borrowed heavily from Irish folklore, often wrote her dialogue in an Irish dialect, and injected delightful whimsy into her horror. “The Banshee’s Halloween” tells of a young Darby who has been tasked with taking tea to a dying woman on Halloween night. Not only is the night stormy, with thunder and lightning, but Darby also fears encountering the terrifying banshee, whose wails foretell death. Here’s how he begins his journey:

Howsumever, ‘twas not the pelting rain, nor the lashing wind, nor yet the pitchy darkness that bothered the heart out of him as he wint splashin’ an’ stumbling along the road. A thought of something more raylentless than the storm, more mystarious than the night’s blackness put pounds of lead into the lad’s unwilling brogues; for somewhere in the shrouding darkness that covered McCarthy’s house the banshee was waiting this minute, purhaps, ready to jump out at him as soon as he came near her.

And, oh, if the banshee nabbed him there, what in the worruld would the poor lad do to save himself?

After several false scares – a screeching owl, lightning flashes – poor Darby does indeed encounter the banshee; but “The Banshee’s Halloween” cleverly follows a traditional trickster folktale, and Darby figures out a way to save himself.

I hope by now you’re intrigued enough to seek out the work of some of these remarkable authors; all of the above can either be found online, in my book A Hallowe’en Anthology: Literary and Historical Writings Over the Centuries, or in Volume 1 or 2 of Weird Women.

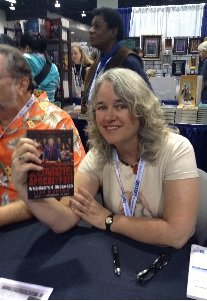

Lisa Morton is a screenwriter, author of non-fiction books, and prose writer whose work was described by the American Library Association’s Readers’ Advisory Guide to Horror as “consistently dark, unsettling, and frightening.” She is a six-time winner of the Bram Stoker Award®, the author of four novels and over 150 short stories, and a world-class Halloween and paranormal expert. Her recent releases include Night Terrors & Other Tales and Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances; her short stories have appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2020, Final Cuts: New Tales of Hollywood Horror and Other Spectacles, and In League with Sherlock Holmes, among others. Her weekly original fiction podcast Spine Tinglers is now live at My Paranormal Network, and September saw the release of Weird Women 2, co-edited with Leslie S. Klinger . Lisa lives in Los Angeles and online at www.lisamorton.com.

American Library Association’s Readers’ Advisory Guide to Horror as “consistently dark, unsettling, and frightening.” She is a six-time winner of the Bram Stoker Award®, the author of four novels and over 150 short stories, and a world-class Halloween and paranormal expert. Her recent releases include Night Terrors & Other Tales and Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances; her short stories have appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2020, Final Cuts: New Tales of Hollywood Horror and Other Spectacles, and In League with Sherlock Holmes, among others. Her weekly original fiction podcast Spine Tinglers is now live at My Paranormal Network, and September saw the release of Weird Women 2, co-edited with Leslie S. Klinger . Lisa lives in Los Angeles and online at www.lisamorton.com.

Get your copy of Weird Women 2 on Amazon.