Halloween Haunts: Heady Ritual, Deviant Day by L. Andrew Cooper

Not yet at th e time of this writing, but on October 31, 2014—barring unforeseen circumstances, such as stepping into an open hole in the sidewalk and being impaled on the metalwork below—I will spend much of the day writing a short story. This year is the 22nd in a row for which my big Halloween plans are to be completely antisocial until I have produced a draft of something horrific, which I will then share with my partner and a close circle of friends and family. Not only is the voting-age status of this ritual an undeniable trump card for party invitations—I tend to view extended social gatherings larger than four or five as survival games—but the aforementioned reading circle now expects that late on Halloween, or perhaps early the next morning (my single-day drafts sometimes run 20+ pages), they will receive, like a present from the cat on the doorstep, something disturbing in their inboxes.

e time of this writing, but on October 31, 2014—barring unforeseen circumstances, such as stepping into an open hole in the sidewalk and being impaled on the metalwork below—I will spend much of the day writing a short story. This year is the 22nd in a row for which my big Halloween plans are to be completely antisocial until I have produced a draft of something horrific, which I will then share with my partner and a close circle of friends and family. Not only is the voting-age status of this ritual an undeniable trump card for party invitations—I tend to view extended social gatherings larger than four or five as survival games—but the aforementioned reading circle now expects that late on Halloween, or perhaps early the next morning (my single-day drafts sometimes run 20+ pages), they will receive, like a present from the cat on the doorstep, something disturbing in their inboxes.

The first story, written in my mid-teens, is untitled and only a few pages long. I now think of it simply as “October 31.” A suburban neighborhood on Halloween night starts undergoing several inexplicable transformations. A young boy watches from his high bedroom window as spree killers go from house to house, as a neighbor transforms into a gargoyle, and of course these forces collide, and the boy is unaware that another strand of narration, a woman going mad, is actually his mother on the stairs to his room, carrying a knife.

The second story, which I would consider rewriting had “torture porn” not come and mostly gone in intervening years, is called “Café Monday.” It’s about a little restaurant where rich patrons pay to have waitresses be rude to them so that, after the meal, they can go with their waitresses to a back room and have some very extreme revenge.

People ask me “Why horror?”, and since I studied the topic for my PhD dissertation, I have quite a few wily answers. But the honest answer is that I have always written, read, watched, and immersed myself in horror, dressing up as a vampire at age four, hanging posters of Freddy Krueger on my wall in the third grade, starting my first (incomplete, and one hopes lost) horror novel, Pyromaniac, in the fifth grade and another, Revelations (also incomplete, lost) in the eighth. The most honest answer I have to “Why horror?” is simply ALWAYS.

Whether it’s an early Ministry single or a line from a Type O Negative song that my friend Melissa used to play better than they do on her guitar, “Every Day is Halloween” is a Goth cliché, certainly. I’ve only been publishing my fiction for a few years now, so I’ve only been mingling with HWA types for a little while (maybe a few of you remember a grad student who lurked a little over ten years ago, but I wasn’t publishing, so I didn’t mingle or stay). Publishing and getting involved with the HWA has helped me realize consciously what I’ve known on some level for twenty-one years and counting: Halloween is the time of year when other people are most curious about what it’s like in our heads every day.

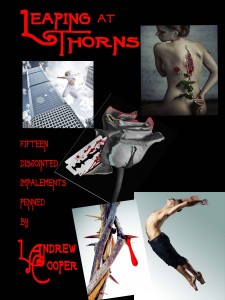

L. ANDREW COOPER’S first collection of short stories, Leaping at Thorns, was just released by BlackWyrm Publishing, Sept. 19, 2014. 13 of the 15 tales were first drafted on Halloween. Previous work includes the horror novels Burning the Middle Ground (2012) and Descending Lines (2012), the latter of which Kirkus describes as “a Grand Guignol cat-and-mouse tale” and “an undeniably horrific thriller.” Cooper also wrote the non-fiction studies Gothic Realities (2010) and Dario Argento (2012). He directs the program in Film and Digital Media at the University of Louisville, where he is Assistant Professor of Humanities. He holds degrees from Harvard and Princeton, but don’t hold that against him. You can find his work at www.amazon.com/author/landrewcooper, his homepage at www.landrewcooper.com, and his Facebook headquarters at www.facebook.com/landrewcooper.

Read an excerpt from LEAPING AT THORNS by L. Andrew Cooper

Read an excerpt from LEAPING AT THORNS by L. Andrew Cooper

from the story “Hands” (first drafted Halloween, 1996, rewritten countlessly, let go June, 2014)

The water around his calves was really annoying. It had taken a long time for him to realize why the water was rising so quickly. He had known that the rain was coming down harder, but not that hard. But then he had remembered where he was. The wasteland sloped downward toward the highway, but the highway was elevated, separated from the field by a high concrete wall with a triangular base that was a great ramp for skateboards. All the rain, then, that ran down the slope of the field was stopped by the wall and the ramp, funneled into a man-made valley. During really bad storms before they had stripped the field for construction, something like a creek had run through the valley, and now, when it rained, it sometimes reappeared, only to disappear shortly after the rain stopped. Martin had never wondered how all the water drained so quickly, but now he knew. He was standing in a very large drainage ditch.

The whole scenario had the makings of a really great adventure. He was like the heroine in an old movie, waiting to be rescued, but time was running out! The villain had designed the trap ingeniously, and, thinking there was no way she could escape drowning, he had left her, laughing all the way, confident that the hero would never find her. But the hero would come, of course, just in the nick of time. Martin was fairly sure, though, he was in no danger of drowning. It would take a miracle for the hole to fill up to his height (just under five feet—he would be tall, everyone said, as soon as puberty hit), and even if it did, he actually thought it would be a good thing because he could just float, and maybe, then, the water would keep coming, and he would be able to swim out. He imagined that the chances of drowning and swimming out were about the same. And there was still another problem with the scenario: a boy could not be the heroine. She, in fact, was already dead, as the pieces of her could testify. So she was nothing to be afraid of, and he was a boy, not in need of rescue.

Aside from the eye, the openness of which looked a little gruesome, the rest of her face (her cheeks were now visible) looked quite serene. Martin wouldn’t be squeamish this time, no way, because she looked almost nice. Martin had seen undertakers do worse jobs making their dead look alive. His mother’s face had looked like plastic, not nearly as nice as this one. The mud on her lips was almost completely gone now, too, and Martin thought that she must have been beautiful. He suddenly wondered what her voice sounded like. He imagined the head speaking to him like something out of a horror movie or in the Haunted Mansion at Disney World, and his imagination tried to give it a voice. The first voice that came to mind was that of Cindy Shuman, a girl in his art class. She was a really good painter, but she wasn’t nearly as pretty as this woman must have been, or was now. And her voice was too high—too, well, girlish. This was a woman. The next voice that came to mind was, of course, his mother’s, but he had seen enough movies to know that he shouldn’t go identifying the corpse with his mother because then it really would start talking to him. He finally settled on the voice of his third grade teacher, Mrs. Parker. She had been really nice and generally non-threatening, and he decided that assigning a non-threatening identity to this corpse would be a psychologically sound thing to do. He congratulated himself on his precociousness.

While her face looked as if it had been deliberately placed there, her hand did not. He could see almost to the elbow now, and somehow its position seemed wrong. First of all, her hand was pointing outward, at him, and the fingers were curled as if they were about to be dipped in dish soap like in that old TV commercial on YouTube. They did not curl down toward the ground, though, but more to the side, making the position of her hand seem disjointed from the position of her arm, as if someone, a man, had twisted her wrist until it had snapped. The arm had one advantage over the face: it was higher up in the mud wall. Though she looked into his eyes when he sat, she looked at his knees when he stood. The water was getting closer and closer to her chin. Martin decided that he liked looking in her eyes. He sat down and hugged his knees into his chest, trying to keep himself from shaking in the itchy water. He looked at her, smiled at her, and closed his eyes. The rain came down harder, splashing his eyelids.

#

He didn’t sleep, but he dreamt. Erosion of dirt, erosion of skin, erosion of thought—his thoughts—he listened to them, only sometimes understanding. He thought about not having any arms and remembered what it was like to have arms even though it was so long ago he could hardly remember. He thought about when his shoulders didn’t hurt and what it was like to be warm. He thought about sitting by the fireplace one winter with his mother and father and big brother, the Christmas two days before they found out about the biopsy, about how he had wanted to stick his hand into the fire just to see what it felt like. They hadn’t let him. He wished now they had, because the memory of being on fire would have been enough right now. He imagined towels after he got out of the swimming pool at the club, but he remembered the time his brother threw his towel in the pool when he asked him to hand it to him as he got out. He loved his brother. He thought about openness and tried to remember what it was like not to be in a coffin because that was where he was, trapped inside and pushing against the walls and screaming about how much he wanted to get out, how horrible it was to be buried alive, and he wanted to punch the boards all around him but he couldn’t because he had no arms or hands, but maybe he was a ship in a bottle, sailing somewhere, or a message, encapsulated by earth and sailing to some distant shore to tell them what life was like here, to tell them not to go anywhere but to stay where they were and not to trust their parents or their friends because they die and lie, and they forget you, and he supposed Mrs. Parker was a message, too, or part of one. Some part of her had gotten lost, or someone had taken what they needed and left the rest behind.

^ What Andrea just said. 😀

How awesome would that be to just have one appear in your inbox? 🙂

Where do I sign up for a yearly Halloween Story? 🙂