By Tom Joyce —

By Tom Joyce —

Martial arts, like horror, was one of the genres that grabbed the film industry by the grindhouses in the 1970s and changed pop culture history forever. In their lavishly illustrated new book These Fists Break Bricks, Grady Hendrix and Chris Poggiali tell the story of the martial arts film boom, and the international coalition of performers, filmmakers, distributors, theater owners, and promoters who made it happen. In his foreword, rapper, producer, and filmmaker RZA describes how the movies inspired young people like him in those troubled years, and brought them a multicultural and gender-inclusive perspective.

According to Grady and Chris, the rise of 1970s grindhouse horror and martial arts films had many parallels. They were fueled by some of the same cultural and market forces, including the widespread social and racial tensions of the decade. In this month’s edition of Nuts & Bolts, Grady and Chris talk about the first filmmakers to recognize the entertainment value in combining martial arts action with horror, and what today’s horror writers can learn about storytelling and promotion from the artists and entrepreneurs featured in These Fists Break Bricks. Grady and Chris collaborated on the following responses.

Q: Can you talk a little about the pioneering work of the filmmakers who first combined martial arts and horror?

Q: Can you talk a little about the pioneering work of the filmmakers who first combined martial arts and horror?

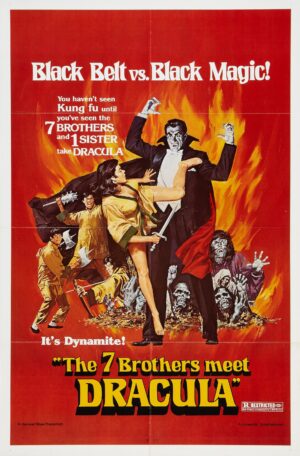

A: One of the earliest fusions of horror and kung fu was 1974’s The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires, a co-production between England’s Hammer Film Productions and Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers. It was a box-office failure and didn’t get released in the US until five years later, trimmed by 20 minutes and retitled The 7 Brothers meet Dracula. The only other early ones that come to mind are two from the Philippines featuring Rosemarie Gil as a woman named Manda who has snakes for hair, Devil Woman and Bruka, Queen of Evil. Although produced in the early ’70s, both of these played in US grindhouses and drive-ins during the latter half of the decade.

By then, The Exorcist had changed everything. It was the second-highest grossing movie of the year in the US and won two Oscars. Shaw Brothers, the powerhouse Asian movie studio, distributed it across the region where it made a ton of money so they immediately began making knock-offs like Ho Meng-hua’s crunky, chunky Black Magic (1975) and the even more pustulent Black Magic 2 (1976).

That was followed by Kuei Chih-hung’s reprehensibly disgusting and totally entertaining horror films like Hex (1980), Bewitched (1981), and the incomparable, incomprehensible Boxer’s Omen (1983). Sammo Hung’s Encounters of the Spooky Kind in 1980 kicked off a whole wave of horror kung fu comedies in Hong Kong for the next five years; some of them were good, like Kung Fu Zombie and the Sammo-produced Mr. Vampire, while others were terrible (Dragon Against Vampire, anyone?).

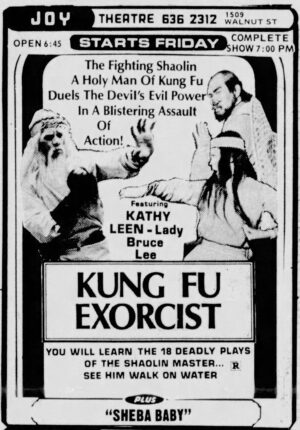

However, most of the “creepy fu” movies visually represented in our book These Fists Break Bricks have no horror or supernatural elements whatsoever – they were just sold that way through deceptive ad campaigns and/or new titles such as Kung Fu Exorcist, Kung Fu Halloween, The Ghostly Face, The Invincible Devil, Dragon vs. Dracula, and Dragon Zombies Return.

Q: In the 1970s, both martial arts and horror movies enjoyed a boom despite being ignored, dismissed, or banned by the mainstream. Why the hostility? And the enthusiasm?

A: In a way, martial arts movies had the benefit of hitting it big four or five years after the establishment of the MPAA ratings system that gave most of them an R rating for violence. Up until 1968, when Rosemary’s Baby was released and movies started getting hit with R and X ratings, kids were largely considered to be the target audience for horror movies. During that “monster kid” craze from roughly 1957 to ’67, Hammer movies and even Roger Vadim’s Blood and Roses were getting booked as kiddie matinees.

It wasn’t until Roger Ebert wrote a whole article in the Chicago Sun Times about witnessing a theater filled with small children scared out of their wits by Night of the Living Dead at a kiddie matinee in suburban Chicago in 1969 that exhibitors started thinking, hey, maybe these horror movies aren’t really appropriate for pre-teens. By the time 5 Fingers of Death and Fists of Fury came along, audiences knew they were R rated for a reason.

In addition, both genres have always run afoul of cultural gatekeepers. For martial arts movies it’s partly because they’re violent but mostly because they’re made by and usually consumed by a non-white audience. One reason kung fu movies took off in the States in March, 1973 was because audiences were hungry to see themselves onscreen and here were movies that didn’t have a single white person in them. You had Asian people as the heroes, the love interests, the villains, the background actors. Black and Latino audiences embraced these movies with a passion and for a lot of US distributors and audiences that meant that these movies were associated with crime, poverty, and having fun.

One of the reasons kung fu movies made it onto TV screens in the ‘80s in packages like “Black Belt Theater” is because white suburban kids wanted to see what was cool and their parents would rather have died than let them go see these movies in what they regarded as the dirty dangerous theaters in poor neighborhoods.

Q: What do you find engaging and entertaining about classic martial arts movies? Any takeaways for creators of horror fiction on getting a story across?

Q: What do you find engaging and entertaining about classic martial arts movies? Any takeaways for creators of horror fiction on getting a story across?

A: The people making these movies knew what their audience wanted and they gave it to them. Even a studio like Warner Bros couldn’t screw it up too badly. You want ass-kicking? We will give you ass-kicking. You want sex? Here are some buff dudes with their shirts off and some women with their breasts out. You want music? Here’s a band we hired to play in the background of this nightclub. Less message, more movie.

And we can’t stress enough the importance of eye-catching ad campaigns, the more outrageous and exploitative the better. After Warners struck box-office gold with 5 Fingers of Death and its iconic poster art featuring actor Lo Lieh’s fist smashing through a brick wall, it wasn’t a surprise to see an indie company like American International release a movie a few weeks later with similar artwork depicting star Angela Mao kicking through a brick wall.

However, they took it to a whole new level of brazen ballyhoo by calling this film Deep Thrust (to also cash in on the concurrent Deep Throat controversy) while describing their leading lady as “The mistress of the death blow!”

Q: According to the book, the story of the martial arts boom is largely the story of scrappy artists and entrepreneurs working around a system that excluded them. What lessons do you think modern writers and publishing professionals can learn from their story?

A: Find your audience and keep giving them what they want. And keep changing it. People wanted kung fu, and then Bruce Lee entered the picture. He died, but an entire Bruceploitation genre sprang up in his wake. And once audiences got tired of that, distributors were ready with Black martial artists who were the new thing.

Then Chuck Norris came along. They tried Jackie Chan, he didn’t work, they ditched Jackie Chan. Then it was ninjas. Always be looking for the next big thing and never be scared to change.

Q: Do you have any advice about marketing a book like “These Fists Break Bricks?”

A: The one thing we learned from these distributors is that the poster and the title of your movie are vital to selling it. So spend more time on your title and your cover. It’s worth it. Sometimes they’re the only thing that people remember.

Q: Where can people follow you online?

A: We have a website! thesefistsbreakbricks.com

|

Chris PoggialiChris Poggiali is a librarian, film historian, and Rondo-nominated writer who edited the fanzine Temple of Schlock from 1987-1991 and brought it back as a blog in 2008. He has written about film for numerous magazines, websites, and DVD/Blu-ray companies. His forthcoming book, co-written with Michael Gingold, is Armies of the Night: ‘The Warriors’ and its Legacy (1984 Publishing, 2025). |

|

Grady HendrixGrady Hendrix is the New York Times-bestselling author of Witchcraft for Wayward Girls, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, and many more. His history of the horror paperback boom of the ’70s and ’80s, Paperbacks from Hell, won the Stoker Award for Outstanding Achievement in Nonfiction. You can learn more useless facts about him at www.gradyhendrix.com |

Tom Joyce writes a monthly series called Nuts & Bolts for the Horror Writers Association’s blog, featuring interviews about the craft and business of writing. Please contact Tom at TomJHWA@gmail.com if you have suggestions for future interviews.