Latinx Heritage in Horror: Interview with Carlos E. Rivera

Carlos E. Rivera is a Costa Rican queer writer and former English teacher. His debut novel The Local Truth: White Harbor Book 1, peaked at #4 in Amazon’s new releases in horror by LGBTQ+ authors.

As an anxious, introverted kid growing up in Costa Rica during the 80s and 90s, he always felt like something of an outsider. His refuge was escaping into and devouring sci-fi, fantasy, drama, crime thrillers, and above all things, HORROR. For years, these books, movies, comics, and even video games became his life.

He plunged into the horror-next-door of Stephen King, the ineffable cosmic abominations of H.P. Lovecraft, the disturbing atmosphere of Silent Hill, the dreamlike imagery of David Lynch, the sheer unnerving strangeness of Junji Ito, and many more; they got mixed in with his country’s folk stories and his own experiences, resulting in a peculiar blend that you, the reader, might perceive as familiar but askew. For Carlos, horror begins with something mundane that, seen from a certain angle, feels a bit off.

Other releases by Carlos E. Rivera are the short horror story “Esperanza”, based on a Costa Rican superstition about a bug that grants good fortune, and the novella I Am the Door, a standalone prequel to his “White Harbor” trilogy.

What inspired you to start writing?

I grew up in a small town in Costa Rica called Siquirres. Being the gay kid in a small, fairly religious, Latin-American town can lead to a pretty lonely childhood, which meant I had to use my imagination to keep myself entertained. I loved writing and making up little stories (which, unfortunately, I rarely shared). Siquirres was just the perfect kind of place to entice that imagination. Small towns, with all of their idiosyncrasies, prejudices, beliefs, secrets, and legends, are a breeding ground for tales. Everyone knows everyone, which fuels the local gossip, and all of this just adds to this “imaginarium,” where every place has a story to explore.

What drove me to start writing was this idea of taking that rich mindscape, and bringing it to a new setting—a different town, a different country—transforming it into something else within my own stories, and seeing how people from other places reacted to it. I want to cause this sense of familiarity/unfamiliarity in readers; this idea of “I’ve read something like this, but there’s something a bit off about it.”

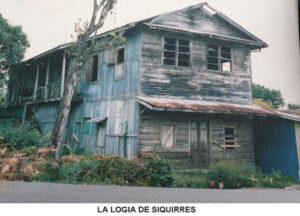

This was the actual house across from mine. (Not pictured: the taco place next door… It kills the mysticism, unless… haunted tacos?)

Probably my favorite example is the abandoned masonic lodge across the street from my house when I was a kid (see the picture below). People from my grandparents’ time saw this through the eyes of catholic, small-town, country folk, and they didn’t understand what was happening in that place, so they came up with all of these stories about witchcraft and satanic rituals. There was this ceremony practiced at the lodge during funerals, which they called “the walking of the dead”, which was basically parading the deceased in their casket around town while dancing and playing music—celebrating the person’s life—but to the locals, this became this legend of a coven of witches making the corpse walk on its own all the way to the graveyard. This story actually made it into my debut novel, The Local Truth, as one of the legends the kids tell each other about the local creepy house.

What was it about the horror genre that drew you to it?

It’s very cathartic. For someone introverted, the world is full of fears, on top of all the scary realities of just existing as a human being. So, having a place where you can face those fears, but contained within the safety of a book, it lets you experience the thrills, the uncertainty, and the adrenaline boost, without actually having a Lovecraftian monstrosity crushing you under its pinky toe.

There’s also the catharsis of trauma. I like to read stories where I can relate to the characters’ painful experiences, whether I’ve gone through them myself or not. There’s this empathy that grows within you reading about others going through trauma, and dealing with trauma, and overcoming trauma, and very few genres do that as well as horror. With horror, your psychological traumas become actual tangible monsters, or curses, or hauntings, and it’s fascinating seeing how different characters deal with them.

For me, taking my own trauma, transforming it, and putting it on the page helps me exorcise it and retake the power it had over me.

Do you make a conscious effort to include LatinX characters and themes in your writing and if so, what do you want to portray?

Yes, I do. In my novel, my protagonist, Peter Lange, is half-Latino. His father was Latino, and you might notice Peter’s last name isn’t, which is a conscious choice within the story. A big part of the story deals with Peter’s authoritarian mother, and her erasure of his father’s influence from his entire life and his entire identity. He has resigned himself to this erasure for fear of his mother, but there’s this part of him that yearns for that father he never truly got to know.

In the upcoming Book 2 of my White Harbor trilogy, another character enters the story, named Alberto Ruiz, who, unlike Peter, actually chose to part with his parental heritage, but slowly has to find his way back to it and make it his own.

Within my novels, you’re probably not going to get this explicitly Latinx tale—I feel many other authors are doing that much better than I can. What I like to work with are themes which can be easily recognizable as inherently Latinx, but someone who isn’t Latinx can also relate to: themes of familial expectations, religious expectations, social expectations, gender expectations, that any Latinx can recognize weigh heavily in Latin American culture, but which other cultures can also relate to in their own way. I want to take those things I love about my Costa Rican tales and folklore and just toss them into your home, where they can make you uncomfortable, regardless of your heritage.

There’s this sauce in Costa Rica named Salsa Lizano—our version of Worcestershire sauce—and it’s what gives Costa Rican food this very specific taste you can’t quite describe, but it’s very much ours. So, while I grew up reading Stephen King, and H.P. Lovecraft, and Alvin Schwartz, what I want to do most of all is give you the “classic American horror novel” with a dash of Salsa Lizano.

What has writing horror taught you about the world and yourself?

I’ve learned that all of those monsters we grew up with are human; they’re a reflection of our humanity, and it’s our job as writers to dig deeper to find those ugly things we don’t want to face about humanity within our monsters. I can describe a horrifying creature to you, and you can say, “Oh, that’s so freaky!”, but what makes it truly terrifying is linking those descriptions to a human behavior, a human fear, a human insecurity. Frankenstein’s monster didn’t know it was a monster until it encountered humanity.

When I was a kid, we talked about La Segua, which is this gorgeous woman that asks drunk men for a ride on their way home from the bar, and after getting in their car—or cart, or horse… this is an old tale in my country—she transforms into this monster with a horse’s skull for a head, and she either kills them violently or scares them to death. As a child, that was just a scary story about a local monster; now, I can see so many meanings behind it: a cautionary tale for drunks, or womanizers, and even going further than that, about toxic masculinity, because you can be sure those men in the stories were expecting something in exchange for that ride home but were surprised to encounter a woman that fought back.

Writing horror has developed within me that sense of: “Sure, I can write about a monster killing people, but if I want it to truly get under your skin, there has to be a dark piece of our humanity within that monster that makes it be and makes it kill.”

How have you seen the horror genre change over the years? And how do you think it will continue to evolve?

It’s been fascinating to see how horror deconstructs and reconstructs itself and adapts to its environment, while still finding ways to be transgressive. Horror has always sort of been the “rebel” genre that says, “Oh, you think we’re getting too smart to be afraid of ghosts? Well, do I have something for you!”

As we move forward as a species and a society, we’re still discovering new stories, new monsters, from places we’d never experienced before. There are so many people in the Americas that had never even heard of Junji Ito, who has written and drawn some of the most disturbing stories ever put to a page, and now, as distances become shorter, new generations are learning of his existence and being influenced by it. Thank you, internet!

As technology and interconnection grow, so do the many things we fear. We’ve reached a point in technology in which we can chat with AI, and it has confirmed fears we’d only theorized about because most AI robots and chatbots end up devolving into racism and genocide.

Social media has unearthed horrors of humanity and darkness that we only guessed existed. It’s a minefield of things that can go wrong. Cyber bullying, doxxing, science denial, sexual exploitation, etc. I didn’t know there was such a thing as depression caused by online perception until social media existed—then Black Mirror made an episode about it, of course.

It’s a great time to be scared! I can’t wait to see what up-and-coming authors find in this new landscape that can be transformed into the next big generational fear.

How do you feel the LatinX community has been represented thus far in the genre and what hopes do you have for representation in the genre going forward?

On the one hand, I feel we’ve taken great strides in our representation in all sorts of genres, not just horror, and when I look at the landscape of horror, when I look at authors like Gabino Iglesias, Agustina Bazterrica, Aquino Loaiza, and Mariana Enriquez, it tells me we’re growing; we’re getting our voices out there. We’re getting louder, and that’s beautiful.

On the other hand, I feel like we still have a long way to go. I feel when the world thinks of Latinx culture, they think of Mexico’s Día de los Muertos (which isn’t actually what you see in the movies). They feel we’ve made our peace with the supernatural, so we have nothing to be afraid of, and we have nothing that can scare others, and oh my God, we do.

I hope to see more of us coming into the spotlight, showing a different approach to horror than what the world is used to.

I’ve always said horror begins with unfamiliarity, and Latinx cultures are so diverse, with so many things that are “unfamiliar” to others; let’s get them into people’s brains and people’s homes and give them new things to fear.

Who are some of your favorite LatinX characters in horror?

I really enjoyed reading Mario in The Devil Takes You Home by Gabino Iglesias. I think he crafted a complex character stuck in a series of terrible decisions, for reasons he feels are the right ones. I think it’s kind of as if Breaking Bad was a horror novel. I like authors that don’t feel they need to sanitize their character because the character is Hispanic. I want to get all the raw, ugly complexity of humanity, because we all live it, we all experience it, and I think Gabino did an amazing job with that.

If I can go the funny horror route, from a non-Hispanic author, if you read David Wong’s This Book is Full of Spiders, there’s a small character there that I love named Carlos. No, I don’t love him because we share a name, but because of the gruesome, atrocious things he does to people who make the mistake of sitting on the ground while he’s burrowing under the earth—yes, you read that right, so you can picture what Carlos does.

I think the fact that I haven’t been able to pick that many characters off the top of my head should be enough of a sign that we need more Latinxs in prominent roles in horror!

Who are some LatinX horror authors you recommend our audience check out?

I’ve mentioned a couple already, but I want to give a shout out to Aquino Loaiza, a queer author of Chilean descent who wrote a wonderful cosmic horror novel called Deep. Absolutely worth the read, if you’re into cosmic horror, cults, and otherworldly entities. He does a wonderful mixture of the “unlikeable” protagonist with the likeable supporting cast that creates tension between the story and the reader. It’s incredibly fun to read.

What is one piece of advice you would give horror authors today?

Horror is meant to horrify, and horror is subjective. Don’t limit yourselves by fearing what other people might dislike about your writing. We write about the ugly, dark, cruel, and bloody parts of humanity; so, assume someone will not like that and make your peace with it. You owe your readers honesty, not coddling, but above all things, you owe yourselves honesty. Write your story the way you want to write it, because once it’s out there, it’s forever tied to your name, so do you want something out there that isn’t what you meant to put out into the world?

One more thing, and it’s what I’ve been saying throughout this whole interview: unfamiliarity is the beginning of horror; look outside for what others are unfamiliar with, and for what you’re unfamiliar with. If you do that, you’ll find endless sources of inspiration.

And to the LatinX writers out there who are just getting started, what advice would you give them?

Your name being Hispanic is not a bad thing.

I struggled for a long time coming up with “more commercial” pen names. Carlos is the 3rd most common name in Latin America after José and Juan. Rivera is the 12th most common last name in Latin America. Triunfo, my second last name, is uncommon—coming from a chosen last name by my Chinese grandfather—but most English-speaking countries barely use second last names, if at all. In my head, of course, I had to change it!

Charles Rivers, Charles R. T., Victor Rivers (from Triunfo = Triumph or Victory) were some of the pen names I tried, but none of them felt like me. This was my story, so I wanted it to be mine. I wanted my old man to see his last name on his son’s published work. So, I stuck with Carlos E. Rivera (E for Esteban, my middle name). Pen names are totally fine, but if your reason to change your name is “it sounds too Hispanic, which is less commercial”, at least stop and rethink it.

And, just like your name, remember there’s value in your local culture, your local legends, and people not familiar with your culture will find them fascinating. Sure, they turned the legend of La Llorona into a terrible Hollywood film, but maybe you can turn it into a novel that will give people nightmares for generations.

There is value in your culture and your heritage.