Halloween Haunts: When Taboo Becomes Tradition by Carrie Lee South

Halloween Haunts: When Taboo Becomes Tradition

by Carrie Lee South

When I tell non-horror people I write dark fiction, their response is often something like “Why? Don’t you want to think about something more positive?” But then autumn’s cold breath brings crisp leaves and suddenly, everyone “gets it.” Halloween. That most American of all holidays. Once a year, the neighborhoods parade out the fake skeletons and tombstones and we all invite death into our lives for a while.

In 1988, as a result of an accidental drowning, my sister died only a week away from her third birthday. Fifteen months later, I was born into that grief. I had an acute awareness of death from my earliest memories.

Every year on her birthday, we gathered to open the chest full of her things. We passed around her toys and her clothes while my parents told us stories about each one: the floppy purple stuffed cat she should have received as a birthday gift, the white Popple with the yellow hair, her bendable Gumby and Pokey figurines.

We visited her grave regularly to polish the headstone with baby oil and leave purple flowers–her favorite color. My younger sister and I rolled around the freshly manicured grass of the cemetery if my parents lingered longer than our attention spans could take. I memorized her epitaph as soon as I could read.

In elementary school, I treated that grief like a fun fact. It was one of the first things I told people upon introducing myself, because I thought it made me sound interesting: I had a sister who died.

Death fascinated me. I knew that someone had been here and then one day they weren’t, and long before I had the language to express it, I tried to make sense of what that really meant.

But around adults, it wasn’t a subject I was allowed to broach. Talking about death in my home felt like waving around a searing hot fire poker. Everyone flinched at the topic, and if I asked directly, I’d be stabbing them with the glowing metal and leaving a permanent scar.

It turns out that avoidance is cultural too–Americans have tried to sanitize death. Embalming with chemicals didn’t even become common practice in the U.S. until the Civil War, when soldiers died far from home and needed a way to be preserved.

For centuries, community members gathered to prepare the body together with the grieving family. It was customary to keep your loved one’s body at home for viewing. Family members would take shifts sitting with the body all day and night until the burial. Then after WWII, Americans wanted to distance themselves from death, so now a funeral home comes to take the body away and prepare it out of sight, out of mind.

But every October, we dress up death and turn it into something fun. We reclaimed it. Sure, you can trace Halloween’s roots back to old European traditions, but the first written appearance of the phrase “Trick or Treat” was in a 1951 Peanuts comic strip.

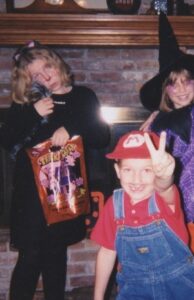

My dad always liked to put on a show for the neighborhood kids on Halloween night. It was our family tradition to take one of his horror movie SFX tapes and put it over the loudspeakers in the garage with the door cracked and lights flickering. Anyone who walked up our driveway heard knives scraping, monsters growling, women screaming, and chainsaws revving.

Then there was the year we rigged a cable from the top of a tree down to our front door. My little sister and I hid by the bedroom window and when someone came to the door for candy, we’d yank a string and a ghost would swoop down at the unsuspecting trick-or-treaters from the treetops.

This wasn’t a cutesy drugstore Halloween. We wanted to scare the crap out of people. One year, dad got a lifelike silicone mask of an old woman. He stuffed his clothing with straw so he’d look like a scarecrow and made movie-quality fake blood out of corn syrup. Then he sat in front of the door, keeping completely still, and holding this nasty blood-covered apple crawling with worms. When curious kids got too close he’d bolt upright and get in their faces: “Would you like an apple, dearie?”

There was always some screaming, jumping, and then? Laughter.

To be afraid is to be human. With our brains flooding with adrenaline and dopamine, we quite literally love to be scared, especially when we know we’re not in any real danger. It’s the thrill of knowing death is possible, combined with the security of knowing that it’s not imminent. It’s why we love roller coasters.

Our world has become increasingly safe. Many of us work from desks sitting in front of computers all day. There’s not much of an outlet for our anxiety. Sometimes, we turn to horror to release that pressure valve. That emotion has to have somewhere to go.

I learned from an early age that things are out of our control. Children die. People get sick. Fear comes for you when you least expect it. One way to confront that terror? Invite it in. Welcome it.

The year we built a breezeway, before we’d covered the fresh dirt with concrete, we made fake tombstones out of cardboard. We spray painted them gray and then wrote fake epitaphs in sharpie. The dirt patch became a graveyard with sawdust-stuffed gardening gloves and boots and things sticking up out of the ground like zombie parts.

Suddenly, cemeteries were funny. We inscribed their fake resting places with puns and silly causes of death:

“Here lies good old Fred / a great big rock fell on his head”

“R.I.P. Ima D. Cayin”

Halloween gave my family a safe way to face death. Instead of a lightning bolt of tragedy slashing through our lives, Halloween normalized it. It’s the time of year when we all come together and look death in the eye sockets.

Horror lovers know this. We all have our own reasons for reading or writing dark fiction. For me, I needed fear that I could control.

When I was twelve, my little brother Robby fell out of a chair in his first grade classroom and misfiring neurons hijacked his body. There was nothing that could save him, or my family, from the cruel, unfair reality that he could die at any moment. His epilepsy diagnosis rattled the tenuous threads holding us together, like prey caught in a spider’s web.

I turned to horror. What fictional fear could compare to my real anxieties? I desperately wanted something that could scare me badly enough to make my troubles feel small, even if just for a moment. I read Pet Sematary under the covers with a flashlight in the dark.

While Robby endured a series of brain surgeries, I disappeared into the pages of Stephen King novels, or creature features like Jaws and Jurassic Park where the danger lurking around the corner was something tangible. Being devoured by a shark in a frothing whirlpool of blood and guts seemed preferable to losing someone to the invisible grip of disease. At least when you close the book, the shark is gone.

For a while, the surgery mitigated his seizures. We all pretended that everything was fine. Like a good American, I closed off that part of my brain and tried to focus on lighter things, like prom dresses, even while I continued to introduce myself as “Carrie, like the horror novel.”

The seizures came back. Sometimes a cluster of them would strike for hours on end, so powerful that he would need to be knocked out with hospital-grade sedatives. Robby described the feeling like an invisible force yanking his arm and dragging him to the floor. The best we could do was hold his head in our lap while he grunted, keep him from falling down or knocking into anything too hard, and count the seconds or minutes until it ended.

If you asked him about it, he would say something about how he couldn’t control it and it was fine, he just didn’t want to be a burden. I would give anything to have this kind of peaceful acceptance.

Robby’s life ended at age 24 in the middle of a seizure like any other. He suffered from a misunderstood neurological disorder that struck him randomly and inexplicably. In the wake of this tragedy, all I wanted to do was write about him. I wanted to write about how hilarious he was, and how wise, and how all he wanted was for everyone around him to be happy.

If you write, then you know this desire to capture someone on a page. But it’s impossible to sum up Robby’s essence in writing. So, when memoir and personal narrative failed to do what I needed it to, I found my voice again through horror.

I write stories that remind me of Robby. I write stories to try and capture that strange liminal space between grief and fear. I write characters that have some of Robby’s qualities, and that’s how I keep him alive. I write stories to control my anxiety in a world where I get to decide how it ends.

I can’t speak for all of us, but when you ask me, “Why do you love Halloween? Why do you write horror stories?”

Memento Mori.

AUTHOR BIO:

AUTHOR BIO:

Carrie Lee South writes stories to keep you awake at night. Her work has appeared in Opus Comics, Tales to Terrify, Iron Horse Literary Review, The Dread Machine, diet milk, and elsewhere. She is working on her first novel. Read more at carrieleesouth.com