By Lee Murray & Geneve Flynn

Lee Murray: As a girl, I remember my Kiwi-Chinese mum lighting joss sticks for the spirits of the dead, always three or five slender sticks since those numbers are auspicious. She would hold the sticks in both hands, the tips glowing red, and bow respectfully, before placing the still-burning bamboo on a stand on the windowsill where the aromatic smoke would curl upwards and permeate the kitchen. I loved that smoky scent. And the solemnity of the moment, quiet amid the general busyness of my childhood. It’s a practice that seems out of place in Aotearoa-New Zealand where Western post-colonial cultural norms dominate, but for us it was an everyday thing. So much so, I thought it was something everyone did, and it wasn’t until I was in my teens that I realised our family was different. I asked Mum what the ritual meant, and she spoke about honouring the spirits of our ancestors, the silvery smoke serving to calm, and also to nourish, departed souls. Although, these were ancestral ghosts, which differed from demons and other god-like manifestations. But being born in New Zealand, I came to realise that there are lot of parallels between Asian concepts of ghosts and gods, and Māori notions of everyday wairua-spirits existing alongside other supernatural forces. Strange too, that Halloween isn’t really a thing in New Zealand; it certainly wasn’t a thing when I was growing up, and it’s only been in the past decade or two that you could buy a plastic pumpkin container for your candy-haul (Kiwis call them lollies). Perhaps the reason for this is that there has always been a sense of isolation here, a loneliness embodied by the harsh beauty of our island landscape and the way the shadows dance on the hillsides at twilight, that you can almost reach out and touch those spirits. In Aotearoa-New Zealand, spirits are ever-present, insidious, here.

Geneve Flynn: Halloween has only really been a thing in Australia in recent years. And it was certainly not celebrated in Malaysia, where I spent the early part of my childhood. For me, it seemed odd to have the spirits so close only on that one day. In Malaysia, spirits were simply accepted as part of the real world, and we took a much more pragmatic approach to navigating their vagaries. They were around us all the time; we just had to know how to live with them. I remember my Chinese mum talking about the Kitchen God, who would look after the family during the year, but who would report everything that had happened in the household back to the Jade Emperor. Nian gao, an extremely sticky cake made from glutinous rice, would be offered to the Kitchen God on the day he was to go back up to heaven. That way, his jaws would be stuck together and he wouldn’t be able to tattle on the lady of the house. My Chinese dad also regaled us with tales of when he would go hunting in the rainforest. He told us the story of an Indigenous guide who laid his parang (a large machete) across a stream to make the water safe to drink. Otherwise, they would have been troubled by meddlesome spirits. My amah (nanny) would point to the geckos crawling up on the ceiling and tell me that I would be taken away by them if I was naughty. My grandmother used to carry the dried penis of a black dog around in her handbag to ward off evil spirits. As I said, pragmatic, and, I think, much less reverential than your family, Lee! But, similarly to the spirit world in Aotearoa-New Zealand, the spirit world in Malaysia is simply part of life.

Lee Murray: I guess the period which most resembles the Western concept of Halloween is the Chinese Festival of Hungry Ghosts, a month-long festival which starts on the fifteenth day of the seventh month in the Chinese calendar. It’s during this time that the veil between the living and the dead falls, allowing the dead to cross back into our realm. And, as you can imagine, those spirits who make the journey back into the world of the living are often pretty upset about still being dead. Because of this, Chinese people take a lot of precautions to avoid their wrath during ghost month. For example, it’s important to show respect for the spirits by presenting them with the best seats at performances or the first choice of any meal, with Chinese families making offerings of fresh fruit and sweet bean cakes to appease any passing ghost. There are some things you can do to avoid encountering a hungry ghost. Young people shouldn’t stay out late at night, for example, for fear a disgruntled ghost might follow them home. People should also avoid noisy activities lest the ghosts become agitated; loud parties are not advised in this month. You shouldn’t go swimming either because ghosts are likely to drag you under. Women wearing clattery high heels risk being possessed. In fact, women, are very often the victims of hungry ghosts, and should take particular care that they don’t attract the ghosts’ attention. This is an idea that I explored in my story “Frangipani Wishes”, which appears in Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women: the notion that stepping outside convention comes with consequences, sometimes to be endured for generations.

Geneve Flynn: Such a gorgeous story. The physical and spiritual world are so fluid in “Frangipani Wishes.” The line between what ghosts are real and what are imagined is so often blurred, evoking the sense that spirits are ever-present. And certainly existent. It’s interesting that while there are many variations of the Ghost Festival across Southeast Asia, the descriptions of hungry ghosts are pretty universal. They’re often a combination of rage and insatiable want, with swollen bellies and tiny, useless throats that don’t allow them to eat. They’re endlessly tormented by unfulfilled desires, forever ravenous in their search for the specific obsessions that plagued them when they were alive. While I understand the caution against greed and excess, it’s revealing that women are often the victims of hungry ghosts, and are advised to be extra careful. It’s almost as if there’s an admonition in there for women to avoid wanting too much…

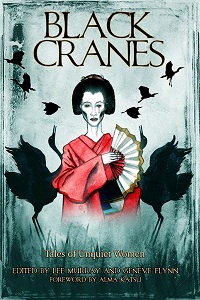

Lee Murray: I agree that for generations the hungry ghost mythology has served to temper Asian women’s expectations, for themselves or for their children. And not just hungry ghosts: tales involving other Asian demons can also be interpreted as metaphor for those gendered barriers. We saw that in our recent anthology project, Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women, where several of our contributors built their stories around traditional Asian demons as a way of exploring traditional expectations. I loved Gabriela Lee’s interpretation of the Philippine’s vampiric tiyanak baby, and the way she deftly used that ‘mythology’ to convey the reproductive constraints on Asian women in an ongoing cycle of duty—and also regret. And you explore a similar idea in your story, “Little Worm”, a richly-woven contemporary tale in which a young woman returns to Malaysia to discover that, in her absence, her mother has created a black magic kwee kia, a devil child, as a means of containing her unrequited ambition. An achingly haunting tale, and beautiful, despite its dark theme.

Geneve Flynn: Thank you, Lee! I think so many of the stories push against these expectations and there’s a certain power to the collection because of that. Alma Katsu wrote in her foreword about the fury threading through the anthology and I think she nailed it. Elaine Cuyegkeng’s story “The Genetic Alchemist’s Daughter” is such a finely wrought tale about existing under that immense pressure; Angela Yuriko Smith wrote about women who are driven to meet impossible standards; Grace Chan’s stories, “The Mark” and “Of Hunger and Fury,” are both about the cost of losing yourself. Rena Mason’s “The Ninth Tale” is about a fox spirit determined to ascend to heaven. Each of these characters is almost like a hungry ghost herself: ravenous for something that’s beyond her reach; existing on the edges; restless, formless, often furious. As the subtitle of the anthology says, “Tales of Unquiet Women,” indeed. In a way, Black Cranes is our Days of the Dead celebration. We’re drawing back the veil and honouring the insurrectionary spirits of women who have the audacity to want more than what they’re told they deserve: what is seemly and proper. On the last day of the Hungry Ghosts Festival, the ghosts are driven back and the gates of hell close again. Somehow, I don’t think the spirits in Black Cranes will be going quietly.

TODAY’S GIVEAWAY: Lee Murray and Geneve Flynn are giving away a print copy of Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women. Comment below or email HalloweenHaunts2020@gmail.com with the subject title HH Contest Entry for a chance to win.

Lee Murray is a multi-award-winning author-editor from Aotearoa-New Zealand. Her work includes military  thrillers, the Taine McKenna Adventures, supernatural crime-noir series The Path of Ra (with Dan Rabarts), and debut collection Grotesque: Monster Stories. Editor of award-winning titles Hellhole, At the Edge, and Baby Teeth, Lee’s latest anthology Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women, edited with Geneve Flynn, released in September 2020. Read more on her website at www.leemurray.info

thrillers, the Taine McKenna Adventures, supernatural crime-noir series The Path of Ra (with Dan Rabarts), and debut collection Grotesque: Monster Stories. Editor of award-winning titles Hellhole, At the Edge, and Baby Teeth, Lee’s latest anthology Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women, edited with Geneve Flynn, released in September 2020. Read more on her website at www.leemurray.info

Geneve Flynn is a freelance editor from Australia who specialises in speculative fiction. She has two psychology degrees and has only ever used them for nefarious purposes. Her horror short stories have been published in various markets, including Flame Tree Publishing, Things in the Well, and the Tales to Terrify podcast. She is a professional member of the Institute of Professional Editors and teaches creative writing courses with Brisbane Writers Workshop.

Geneve Flynn is a freelance editor from Australia who specialises in speculative fiction. She has two psychology degrees and has only ever used them for nefarious purposes. Her horror short stories have been published in various markets, including Flame Tree Publishing, Things in the Well, and the Tales to Terrify podcast. She is a professional member of the Institute of Professional Editors and teaches creative writing courses with Brisbane Writers Workshop.

She loves tales that unsettle, all things writerly, and B-grade action movies. If that sounds like you, check out her website at www.geneveflynn.com.au.

BLACK CRANES: TALES OF UNQUIET WOMEN

“This anthology has a power to it. An instant classic.” —Nightmare Feed.

“A bloody-toothed smile hidden behind the hand of propriety and social expectation.” —Pseudopod

“As haunting and versatile as the Chinese erhu, the stories in Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women pluck and bow the strings of the Southeast Asian experience with insightful depth and resonance.” —Tori Eldridge, author of the acclaimed Lily Wong novels, The Ninja Daughter and The Ninja’s Blade.

Almond-eyed celestial, the filial daughter, the perfect wife. Quiet, submissive, demure. In Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women, Southeast Asian writers of horror both embrace and reject these traditional roles in a unique collection of stories which dissect their experiences of ‘otherness’, be it in the colour of their skin, the angle of their cheekbones, the things they dare to write, or the places they have made for themselves in the world.

Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women is a dark and intimate exploration of what it is to be a perpetual outsider. For more information visit the publisher’s WEBSITE.

This sounds awesome! I grew up hearing Japanese scary stories from my Grandparents. Scared me so darn much lol