Halloween Haunts: Three Generations of Halloween and Horror Love

By Arin Ruhl

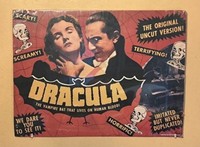

A love of horror is my inheritance on my mother’s side, and Halloween is a family extravaganza. We own more Halloween than Christmas decorations, and perhaps the first time I learned what a vampire was came from an old Dracula movie poster that has hung proudly in our dining room every October for as long as I can remember. Since I was eight years old, we’ve hosted an annual costume party for friends and relatives we don’t often see otherwise. As a kid, I got to chase my cousins and school mates around while we played pretend in costumes. As I’ve gotten older, the main activity is watching a slideshow of photos from past Halloweens and reminiscing. We have idyllic memories of togetherness and skeletons and pumpkins, but like any family, ours also has some tension. My grandmother, mother, and I don’t agree on everything, but our different points of view were shaped by the cultural fears that raised us, and horror remains a unifying interest.

The Dracula poster on the wall of our dining room.

My grandmother grew up in the 1950s at the height of the radiation fears and raised three children as a single, working mom in the 1960s and 70s. My mother tells me that they moved a lot and their life wasn’t very stable due to financial hardship, but her fondest memories of childhood are of horror and Halloween. On special nights, my grandmother would hold her on the couch and they would stay up late with popcorn and orange Kool-Aid to watch Chilly Billy and other horror programs. My mother amused herself by hiding to scare her younger siblings around Halloween…and the whole year, if we’re being honest. To my mother, horror was a bright highlight in a childhood where she didn’t have a lot, a way to escape.

My love of horror and Halloween also started with my mother, though I’ll admit that as a child in the 2000s I did not appreciate horror at all. Childhood nightmares were inspired by such material as the “Living Doll” episode of The Twilight Zone and the giant ants in Them! I scared easily, stayed far away from Goosebumps, and didn’t get why the “boring” black and white movies were impactful. For Halloween, I dressed as book characters in contrast to my mother’s Bride of Frankenstein or creepy witches. I notably had a much more sheltered childhood than my mother. I’m thankful that I never had to worry about what we’d eat or where we would live. It wasn’t until I was an adult—and my life problems got to the point escapism was appealing—that I started to fully appreciate horror.

I wonder, what happened in 2020 to cause an increase in global anxiety and thus greater interest in the horror genre? I’ll spare the recent history lesson that everyone knows and focus on the personal upheaval that started for me in 2020. Early in winter, before the pandemic started, I got a pretty severe flu infection—which is an equally serious virus, may I emphasize. Growing up, I always had some vague indicators that something wasn’t normal in my body, but never enough to concern doctors (who should have been concerned). The great flu of 2020 caused an underlying condition to rear its head and make itself known. Within a year I was diagnosed with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS), which is a rare genetic disease that affects the whole body. It looks different in everyone, but for me, my worst symptoms are joint problems, chronic inflammation, fatigue, and migraines. The latter are weather sensitive, and do you know which time of year triggers the most flare-ups? October.

My tale returns to the Dracula poster that’s been in my family for about as long as I have. Over Halloween weekend in 2022, while confined to the couch with my face buried in ice packs and my blood full of ibuprofen, I got to thinking about the original novel and the 20th century vampire movies. In those stories, when someone starts to experience symptoms of blood loss like tiredness and malaise, their first thought is never “vampire” and the characters aren’t usually willing to believe in the supernatural until someone’s dead. In the novel Dracula, even after the group learns a vampire is on the loose, when Mina suddenly gets sick she doesn’t tell anyone for some reason. As the viewer, we’re entertained by this dramatic irony, but I started to think about it from a disability lens. If a character who had, say, EDS and was used to feeling poorly for no reason suddenly had a flareup of symptoms similar to blood loss, their first thought wouldn’t be close to “vampire” or even “the flu.” They’d assume it was a rough flare-up, and it would make sense why they wouldn’t tell anyone something was up until the situation got dire.

That Halloween was the inspiration for me to become a serious horror writer. My first novel, which I’m currently querying and you can find more information about on my website, is a vampire story about a chronically ill character who takes forever to connect the dots between “mythical bloodsucking creature” and “sudden flare-up” because he’s used to feeling unwell. If someone told me that my time spent knocked down by symptoms was actually the work of a vampire, I sure wouldn’t believe them, although it would be a lot more fun to blame a monster instead of the air pressure.

In my early 20s, it was like a switch flipped. The genre I avoided as a trigger of nightmares became a comfort for dealing with those same anxieties. This is the true power of horror: an escape to analyze real-world fears in a safe and entertaining setting. Halloween is like a roleplay event where you can get an adrenaline rush and process physiological reactions to fright from haunted houses, spooky decorations, and movies instead of the news or doctor appointments.

As I examine what horror means to each of the three generations in my family—my grandmother, mother, and me—I reflect on the different worlds we grew up in and what scares us. My grandmother still carries anxiety spawned by the Cold War and radiation fears, and she tells me her ideas for horror stories about secret government experiments. My mother came of age in the 1980s when the “Satanic panic” began to influence culture, and she avoids possession, haunted object, and demonic horror—except for “Living Doll,” that one’s okay, much to child-me’s chagrin. She does love proto-feminist horror such as Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. I was born in Y2K, and I shared earlier that as a child I wasn’t really engaged with classic horror films, but I did and still do love climate thrillers. As I got older and increasingly aware of real world fears, the idea of fictional scary worlds became much more appealing.

What is the factor that unites the experiences of the three generations of horror lovers in my family? We’re still alive despite how terrifying the world is and has been for all our lifetimes, from the Atomic Age to the 21st century. If the meaning of Christmas is peace and togetherness with your loved ones, then to me the meaning of Halloween is being scared with your loved ones but still being okay at the end of the day.

Arin Ruhl (who writes as R. A. Ruhl) is a member of the Pittsburgh chapter of the Horror Writers Association and has an MFA in Writing Popular Fiction from Seton Hill University. Ruhl lives with a rare genetic condition and writes about disability representation and advocacy. In their free time they enjoy astronomy, visiting museums, and hanging out with a fussy old dachshund. You can find Ruhl’s website here.