Halloween Haunts: The Personal Nature of Horror

Eugen Bacon

As writers of horror, there are many motivations that spur us to write this kind of fiction. Some, perhaps like Eric LaRocca, there’s a certain glee in unsettling the reader. But in an interview on their book This Skin Was Once Mine and Other Disturbances, he shares that horror is, to him, a form of healing. There’s blood and brutality, the Lovecraftian in cosmic horror. In the horrific is a certain truth: ‘awful things happen to everyone’.

This is one reason I write horror—it reflects reality. You have only to turn the news and there’s Gaza with starving children and bombed hospitals. No one is safe. There’s Ukraine and I still recoil from the narration of a surviving soldier (I don’t know if he still lives) who was castrated in captivity. Humans do the most awful things to each other—we’re worse than animals that kill for food or survival.

I write horror to demystify things like death or body horror—what if you woke one day without a face? Your scalp has expanded itself and took over your eyes, your nose, your mouth, your ears? What if you were walking around the botanical gardens, stepped on a landmine and that was that for your limbs?

Sometimes horror is cautionary. I write as a subversive activist with an underlying message that this is how bad things can get if we can’t change… I wrote in my book Writing Speculative Fiction by Bloomsbury Academic:

You think horror, you think Bram Stoker, Alfred Hitchcock, Ridley Scott, M. Night Shyamalan, Dean Koontz, Stephen King, Eleanor Lewis, H. P. Lovecraft, Shirley Jackson, Mark Danielewski, Mary Shelley, Robert Louis Stevenson, Anne Rice, Poppy Brite … Guy de Maupassant who wrote across many genres. In his book Danse Macabre, King paid homage to Jorge Luis Borges and Ray Bradbury in his list of ‘six great writers of the macabre’…

Is horror the jet black eyes of a silent entity, an atmosphere in a room that creaks, footsteps on a wooden floor, objects changing position, pictures turning to snow on the television screen, things falling when no one else is home, a shadow at the edge of your sight, a spectre on a fence by the road, staring little girls dressed in white, weeping walls, crying babies, songs behind a wall, barking dogs, horses going ape, an aura behind a headstone, a silhouette in every photograph, two sets of the same person out of nowhere, poltergeist?

…Horror is personal. A spider may be horror to you. A snake. Height. Blood. Rot. A dead body. A ghost. In An Evening with Ray Bradbury, the author invited his listeners to ‘list ten things you love, and ten things you hate’ and then to write about those loves and kill those hates—also by writing about them. Do the same with your fears, he said.

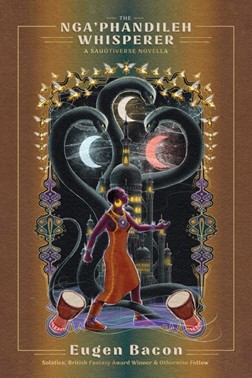

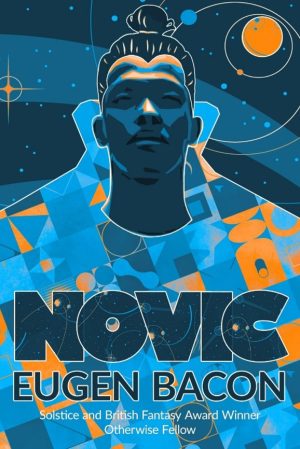

Two of my books out this September explore different aspects of horror.

The Nga’phandileh Whisperer published by Stars and Sabers is a novella that examines our inherent fear of the unknown. The Nga’phandileh are creatures of unreality in the Sauútiverse, an Afrocentric universe of five planets, two suns and two spirit moons. In this novella, a precocious guardian is also a Nga’phandileh whisperer—she can tap into the hive mind, but quickly discovers she has more power than she knows how to use it.

In a different kind of story, NOVIC published by Meerkat Press seeks to demystify death, in its scrutiny of Novic, an immortal priest we first encounter in her novel Claiming T-Mo. In this behind-the-story, a bit like a morbid There’s Something About Mary, I start with the question: what about Novic?

Whatever our motivations for writing horror, a subgenre of speculative fiction, it does what good fiction will do: not only is it an escape, as in a psychological getaway—it can enable responses to global racial, gender, environmental and other crises, by offering a cosmological timeframe and perception. It can help us see the world through a character’s eyes, and prompt us to understand other perspectives.

EUGEN’S UPCOMING WORKS

The Nga’phandileh Whisperer by Stars and Sabers

What critics are saying:

“The Nga’phandileh Whisperer is mythic and ancient, feverish and insistent, lyrical and atmospheric, eerie yet enchanting—an enticingly strange exploration of the power of sound by a poetic storyteller.”

—Ai Jiang, Nebula and Bram Stoker and Hugo Award finalist of A Palace Near the Wind and Linghun

Excerpt:

~

Zezépfeni is a rapidly orbiting planet in the Sauútiverse, and experiences rapid seasonal changes, meteor strikes, and a lingering threat of the Nga’phandileh, beings of unreality. It is a difficult world to inhabit, fortified with technology and magic. This story is set in New Inku’lulu, a Zezépfeni lookalike space outpost—here, Guardians of the tower use special prayer to secure a part of the undisclosed Hogiiri Hile Halah, the bounding wall protecting

the federation of planets from the Nga’phandileh.

~

…You remember the mischief you did on Mama—

You were younger then, just past seven years. It was cruel, what you did. Baba did not smack you to the middle of another year, but he should have. What came upon you to conjure a phantasm, create an illusion that turned a cane toad into a coconut loaf? It was a big toad, the size of two hands and a chin that held its cold slime as you held it back from bounding free. You’d found it behind the cascading waters of the fountain, and clutched at it.

Perhaps it worried you a little, worried Mama too, when she realised the truth of it—did you know how far you meant to go? That was the truth of it: you didn’t. Would you have sat still and watched her lift the breadknife? Would you have surveyed how she held down with curled fingers the live toad as if it were bread? Would you have jumped a little, winced or shuddered had she sliced through with the knife’s jagged edge, sawing skin and halving the toad through its innards all the way to the board? If she wasn’t so shattered, Mama would have smacked you straight into the middle of three days. It was the toad that saved itself, not you, when it croaked out loud and the illusion lifted. Perhaps its croak was a protestation of incarceration between a hand and a cutting board, rather than an outcry in a sentient awareness of the looming terrible death. Whatever the reason, misapprehension slipped and Mama saw the toad in its warts and slime, a white underchin heaving in laboured breathing. She squealed, then, fell silent in a stupor, then found her mind to gaze at you in horror.

Her scream brought your father flying into the kitchen, and he took it all in at a glance. He understood in an instance the malice of your prank. In that bleeding silence that ensued, a centipede propagated its way from the table’s underside. Its multi legs shifted its body along the gait of an entrancing wave that, unsuspecting, neared the toad. The saved creature, oblivious of its luck, rolled out a sticky tongue and gobbled the centipede whole, then leapt away into the courtyard.

~

NOVIC by Meerkat Press

What critics are saying:

“Novic is a brief, thought-provoking novella that explores life and death with quiet subtlety.” —Dontaná Mcpherson-Joseph, Foreword Reviews

Excerpt:

The slow trek of a snow camel took him there. He never looked where he was going. He just went. The course through the mountains was a brace—all tangled. Everything was savage about it: humping ground personified to viciousness, roaring wind unwilling to give any answers. Things crawled at him from the edge of his eye, dissolved when he looked closer. He was a wreck. He felt a wreck. Further still, the horizon ran out of time. The beast he rode on let out a gushy fart as Novic slid off the saddleback. He slapped its rump as the handler said he should, and the camel chewed cud and batted long lashes at him before it turned.

He trusted it would make its own way back down to the cameleer farm he loaned it from. He’d bobbed in weirdness, gently moving his body back, forth, lumbering side to side between its two humps, and the only bother he felt was not from the stiffness of its woolly fur beneath the skinny saddle but rather from the musky odor of it. There was also the sour pungency of the camel’s breath, emphasized at intervals with rancid burps. In essence, it was darn good riddance to let the beast go—he was done holding his breath.

The Temple of Kripps in the Land of Praeyer at a place below zero was off a cut stone path that led up, up to the sky. A sense of doom hovered about it and he didn’t think it was anything to do with the close of daylight. Novic strode on the cobblestones until he reached the imposition of a two-meter door. He hunted for a bell, and nothing remotely resembled one within his spectrum of visibility.

In the non-appearance of a doorbell, he lifted the giant steel knocker that seemed there for a reason, and rapped the tall, thick wood engraved with death masks.

Whose faces? He couldn’t tell.

Eugen Bacon is an African Australian author. She’s a Solstice, British Fantasy, Locus and Foreword Indies Award winner, a twice World Fantasy and Shirley Jackson Award finalist, and a finalist in the Philip K. Dick and Ignyte Awards, and the Nommo Awards for speculative fiction by Africans. Eugen is an Otherwise Fellow, and was also announced in the honor list for ‘doing exciting work in gender and speculative fiction’. Danged Black Thing made the Otherwise Award Honor List as a ‘sharp collection of Afro-Surrealist work’. Visit her at eugenbacon.com.