Halloween Haunts: The Facts in the Case of Edgar Allan Poe

by Joseph Maddrey

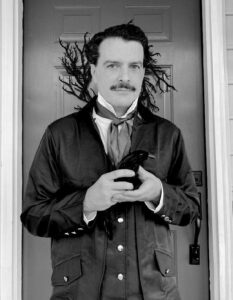

When I moved to Richmond, Virginia in 2021, after fifteen years in Los Angeles, I was disappointed about Halloween. Nobody celebrates Halloween like people in L.A. and I expected Halloween in Richmond to be anticlimactic, so I immediately started looking for the local horror crowd. In September, I gravitated toward the Edgar Allan Poe Museum and decided to embrace my new home by dressing up as its native master of horror on October 31st.

Because I’m nothing if not obsessive, I also started re-reading Poe. In addition to re-discovering his most famous stories and poems, I picked up Arthur Hobson Quinn’s mammoth critical biography of Poe, James M. Hutchisson’s more concise biography, and Chris Semtner’s The Poe Shrine. One of these—or maybe all of them—pointed me toward Poe’s late essay “Eureka,” a philosophical treatise on the power of intuition and imagination, which I’d never even heard of before. Who knew Poe had a multiverse theory? Or that he essentially predicted Einstein’s Theory of Relativity? It seems appropriate that the granddaddy of horror should have pioneered the discussion of black holes, the butterfly effect, and time travel in the 1800s… but this was all news to me.

Like anyone who studies Poe’s life, I became captivated by the details surrounding his death—or, rather, the lack of details. On September 27, 1849, Poe left Richmond on a train bound for Philadelphia. Five days later, he was found semi-conscious in Baltimore, outside a polling place for a local election. He was wearing ill-fitting clothing and could not explain how he came to be there. Presumed drunk, he was taken to a nearby hospital where he spent the next four days in a delirious state, reeling from vivid hallucinations. On the final night, he repeatedly called out the name Reynolds. He died on Sunday morning, October 7, 1849. A physician gave the cause of death as “phrenitis,” or inflammation of the brain.

What really happened to Poe during those five missing days? Everyone seems to have a theory. Some say he was abducted and beaten by relatives of a woman he wanted to marry. Others that he was abducted by political zealots who got him drunk and forced him to vote in the local election multiple times (which would the ill-fitting clothing that was obviously not his). There’s also a theory that Poe was suffering from a brain tumor. Or maybe mercury poisoning, related to a cholera outbreak in Philadelphia a few months earlier. Or the seasonal flu. As of 2021, not one of these theories had been proven… but they were all easy to imagine.

I was mulling over the possibilities when, on October 7 (the anniversary of Poe’s death), my entire family got Covid. My own symptoms began with a headache that intensified overnight until I started hearing a steady, high-pitched ringing in my head. It reminded me of one of Poe’s later poems “The Bells,” an anguished, semi-mad earworm of monotonous horror…

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the throbbing of the bells—

Of the bells, bells, bells—

To the sobbing of the bells;

In my feverish state, I drifted in and out of sleep but never rested because my brain was on fire. I couldn’t stop thinking about Poe and the mystery of his final days. If you’ve ever been haunted by “work dreams,” in which you continually re-visit some specific problem or task, but can’t make any progress or achieve any closure, you understand.

Finally, in the early morning hours, I had an epiphany. In my delirium, I knew exactly what had happened to Poe. Obviously, he had used the staggering power of his imagination to travel through time, arriving in 2021, where he contracted Covid and was hospitalized under the care of an ER doctor named Reynolds. When Poe told the physician who he was, Reynolds joked that Halloween had come early and left the famous poet, obviously unvaccinated, to his fate. As his physical condition worsened, Poe’s mind weakened and he found himself back in 1849, not knowing whether he had actually seen the future or merely dreamed about it. The only “proof” was the mysterious virus that was killing him.

My own illness lasted five days, slowly turning into a malaise in which everything became odorless and flavorless. Life was all texture, no taste. When my mind cleared and I began to feel human again, I remembered the fever dream and wondered if I could turn it into a good short story. I started reading Poe again, gathering details to support my crazy idea.

I learned that Poe wrote his first story about timelessness and deathlessness in 1833. In “MS. Found in a Bottle,” the first-person narrator recounts an experience of a sea storm that swept him onto the deck of an enormous black ship. There, he encountered a crew of weary, ancient-looking sailors, trapped forever in a floating purgatory. Eight years later, in a fragment titled “Colloquy of Monos and Una,” Poe imagined the dissolution of all boundaries between existence and nonexistence, suggesting—in true Romantic fashion—that Everything is One. From “the wreck and the chaos of the usual senses,” he wrote, arises a sixth sense, “the moral embodiment of man’s abstract idea of Time.” In the wake of a “fierce fever” and a “dreamy delirium,” haunted by a sound of “distant bell-tones,” Monos declares that he has achieved deathless Death.

Evocatively describing the sights, sounds and smells of these other worlds, Poe grounds us in alternate realities, making them real for us. That is the awesome power of imagination and storytelling. A good story can transport us into places beyond time, beyond death. Poe wrote not only to transport readers, but to transport himself. By the time he wrote “Eureka,” he had thoroughly convinced himself that time is an illusion and death is not the end.

us. That is the awesome power of imagination and storytelling. A good story can transport us into places beyond time, beyond death. Poe wrote not only to transport readers, but to transport himself. By the time he wrote “Eureka,” he had thoroughly convinced himself that time is an illusion and death is not the end.

In November 1844, Poe wrote, “We appreciate time by events alone. For this reason we define time (somewhat improperly) as the succession of events; but the fact itself—that events are our sole means of appreciating time—tends to the engendering of the erroneous idea that events are time—that the more numerous the events, the longer the time; and the converse.” He made a similar argument about Space: “The fact, that we have no other means of estimating space than objects afford us—tends to the false idea that objects are space.” He concluded that Time and Space are illusions, existing only in our minds. That same year, in a poem titled “Dream-Land,” he pointed out that we routinely escape these constructs in dreams, which exist “Out of SPACE—out of TIME.” In a later poem, he asserted that life is “but a dream within a dream.”

In “Eureka,” Poe wonders about the nature of the boundaries between waking consciousness and dream-life, between time and eternity, between existence and nonexistence. By wondering, he dissolves those boundaries in his own mind… which makes me wonder if his writerly attempts to transcend time and death could have, somehow, produced the mystery of his final days. Clearly, whatever happened to him—wherever he went, in his mind or in the multiverse—contributed to his immortality.

I’m speaking metaphorically, of course… but don’t metaphors shape our everyday reality? How would we experience time and space if we didn’t have words? Don’t words give us the means to formulate our thoughts and beliefs, to communicate these things to each other, to develop a shared reality?

I never did write a short story about my Covid fever dream because the vividness of the dream—my belief in its reality—decamped even more quickly than the fever. That’s what happens to dreams: they fade. Unless we write them down, as Poe did. And then? Sometimes, they take on a life of their own.

The breeze—the breath of God—is still—

And the mist upon the hill

Shadowy—shadowy—yet unbroken,

Is a symbol and a token—

How it hangs upon the trees,

A mystery of mysteries!

– Edgar Allan Poe, “Spirits of the Dead” (1827)

Joseph Maddrey is the author of more than a dozen books, including Nightmares in Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film (2004); Not Bad for a Human, the official biography of film actor Lance Henriksen (2011); Simply Eliot, a biography of poet T.S. Eliot (2018); two volumes of Adapting Stephen King (2021-2022) and the graphic novel To Hell You Ride (2013). He has written or produced over 100 hours of documentary television, including episodes of Discovery Channel’s A Haunting, History Channel’s Ancient Aliens, Oxygen’s Snapped and TVOne’s Payback. He recently co-edited Dark Corners of the Old Dominion, a charity anthology of 23 horror short stories and poems, all set in Virginia and written by authors with strong ties to the state. You can learn more at the publisher’s website: https://deathknellpress.com/dark-corners-of-the-old-dominion/ You can learn more about his other work at https://maddrey.blogspot.com.

Joseph Maddrey is the author of more than a dozen books, including Nightmares in Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film (2004); Not Bad for a Human, the official biography of film actor Lance Henriksen (2011); Simply Eliot, a biography of poet T.S. Eliot (2018); two volumes of Adapting Stephen King (2021-2022) and the graphic novel To Hell You Ride (2013). He has written or produced over 100 hours of documentary television, including episodes of Discovery Channel’s A Haunting, History Channel’s Ancient Aliens, Oxygen’s Snapped and TVOne’s Payback. He recently co-edited Dark Corners of the Old Dominion, a charity anthology of 23 horror short stories and poems, all set in Virginia and written by authors with strong ties to the state. You can learn more at the publisher’s website: https://deathknellpress.com/dark-corners-of-the-old-dominion/ You can learn more about his other work at https://maddrey.blogspot.com.