Let’s assume for the moment that Jaws is, in fact, a horror movie. Cool, thanks.

Let’s assume for the moment that Jaws is, in fact, a horror movie. Cool, thanks.

Now: So what aspect of the Father of the Summer Blockbuster might we study for writing tips?

There are many to choose from in this A+ of a film, but I’m choosing two that probably slipped by unnoticed: One set of three lines, and character backstory.

Police Chief Martin Brody, father of two boys and happily married to Ellen, came to Amity from New York City where he was a police officer. A dangerous job, to be sure. Almost from the beginning, the family seems to wonder if beach life is really all it’s cracked up to be, and Brody’s at odds with the city council and just about everyone else over this minor little shark issue.

About halfway through the film, Brody’s oldest son is brought to the hospital to be treated for shock after seeing a fisherman eaten by the titular character. In the hospital, Brody hands over his sleeping youngest son to his wife, saying, “Why don’t you take him home.”

Half-hopefully, half-joking, Ellen Brody replies, “New York?”

“No,” Brody says, unsmiling. “Home here.”

That’s it. We writers have a lot to learn from this set of three short lines of dialogue.

What’s so great about this minor exchange is its economy. Let’s come back to that.

The story of Jaws is not about Brody wanting to return to New York, or about the trouble his family is having fitting in with this new community. But those conflicts do exist in the story, which brings us to point two: Being the New Guy in town.

If the Brodys were from Amity, then Ellen’s reaction to first meeting the surly shark-hunter Quint wouldn’t have the impact it does; the grizzled fisherman scares her, and makes her all the more scared for her husband who’s going out with Quint and a nerdy scientist to capture or kill a great white. Guess who else it now scares? Yep: Us. If the Brodys were Amity natives, we’d still be worried for the chief, sure. But Ellen’s fear, compounded by her contact with Quint, escalates our dread even more.

This fish-out-of-water arc (if you’ll pardon the pun) is not the primary concern of Jaws, but it’s a great base layer to build this excellent story upon. It makes things harder for the protagonist and it helps move the story along. Again, if Brody was an Amity native, his fights with the town council over closing the beaches (an argument he loses and which leads directly to the near-death of his son) wouldn’t be nearly so incendiary and thus would be much less thrilling overall as the fear over the shark’s rampage grows. The tension on land is real and dynamic.

And as Mrs. Kitner can tell you, Brody’s conflict with the town council has real-world life-or-death consequences . . .

This film influenced my own writing in many ways. For example, in my novel Sick (which is about a sort-of Zombie Apocalypse set at a Phoenix area high school), I chose to have the protagonist not be a “drama kid” despite the bulk of the book being set almost exclusively in that drama department. Why? So the readers — most of whom would not be drama kids — could experience the setting and tropes of a high school drama department through similar eyes. They learn things at the same time my protagonist does. (Astute readers will note that I also cribbed Brody’s famous line for the novel as the characters start to understand just how bad the infection is and how much danger they’re in.)

Jaws uses the same approach. Having Brody be a new guy in town lets us as the audience learn about Amity, and about sharks, at the same pace as the protagonist. Jaws as told from Quint’s point of view would be, I daresay, incomprehensible or boring. If Jaws was told by him, we’d either be horribly confused by his fisherman’s lifestyle and lingo, or bored silly because the story would have to keep stopping to fill us in on backstory, life and politics in small town Amity, etc. etc.

Since Brody is the character we’re following, we learn things at the same rate he does, so the backstory, exposition, science, and so on has an immediacy to us that doesn’t slow down the story.

Now back to the hospital:

When Brody says to Ellen, “No. Home here,” what we’re seeing is Brody turning a corner. In this economical little bit, the writers and director let us know that Brody is in this for the long haul. That damn shark nearly killed his boy. The smart thing to do is move back to New York. But Brody’s had it; this is war now. We’re not running away, honey. Amity’s our home now, and I swear by all that’s holy that I’m gonna make this shark pay for what he did to my son, to that young girl, to that little boy, and I’m not letting it happen to anyone else.

He says all that in three words: “No. Home here.”

In your writing, aim for that kind of economy. There could have been a big fight scene between Ellen and Brody wherein she argues that they should all go back to the Big Apple. And that would have been fine. But not good. Good is just this quick exchange that cements for us Brody’s position and goal for the remainder of the story.

Of course, in a film of this caliber there are plenty of other aspects we could study, but I’ll leave you with that one to consider for your own work.

Just remember: You’re gonna need a bigger boat.

TODAY’S GIVEAWAY: Tom is giving away a new, signed hardcover of his novel Sick. Comment below or email membership@horror.org with the subject title HH Contest Entry for a chance to win.

TODAY’S GIVEAWAY: Tom is giving away a new, signed hardcover of his novel Sick. Comment below or email membership@horror.org with the subject title HH Contest Entry for a chance to win.

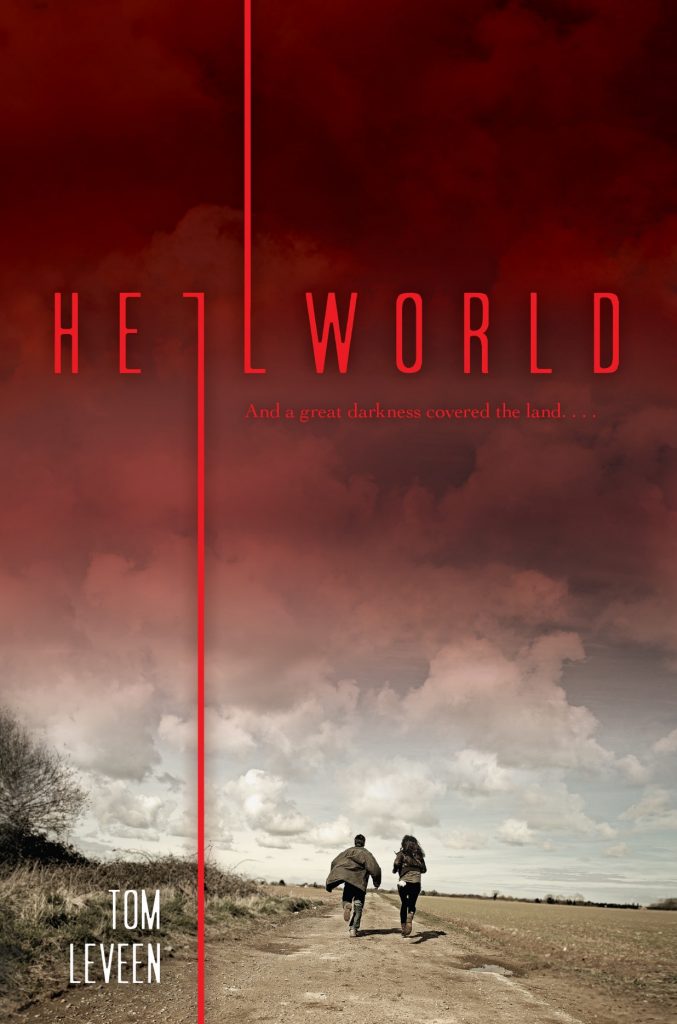

Tom Leveen is the author of seven novels including SICK and SHACKLED and the novella THOSE WE BURY BACK. His eighth novel, HELLWORLD, will be available March 21, 2017. He brings 22 years of theatre experience to his many panels, conferences, and classes. Tom is online at tomleveen.com; Facebook.com/AuthorTomLeveen; and @tomleveen.

Buy SICK here: http://goo.gl/2P6Nwa

Buy SHACKLED here: http://goo.gl/skU53c

Buy THOSE WE BURY BACK here: http://goo.gl/at5wqN

Pre-order HELLWORLD here: http://goo.gl/mGwjwE

Read an excerpt of HELLWORLD by Tom Leveen:

Read an excerpt of HELLWORLD by Tom Leveen:

ONE

Now

There exists a darkness so deep, so profoundly absent any light or hope, it causes dizziness and nausea. In this cave, with no source of light and the bodies of the dead surrounding us, there are already plenty of reasons to experience both.

I think we are in hell.

What have I done?

Charlie’s voice drifts to me through the black. “Abby?”

His breath comes out ragged, as if from between strips of flesh. I shut my eyes against the image. Open them. At least when I blink, I can feel my eyelids moving. That’s something. But there is no difference between open and closed.

“Yeah?” I whisper. The sound goes only as far as my lips. It feels like being in the deep end of a pool, blindfolded, all sensation muffled.

“Selby?” Charlie says, but hesitantly.

Why did he ask for me first, when Selby’s supposed to be his girlfriend? Because I had a better chance of being alive.

No response from Selby.

I listen hard, straining as best I can, trying to ignore the sound of my own heart attempting to fight its way out of my chest. Rocks and pebbles grind into my palms and knees. Finally, to my left, a miniscule whimper needlepricks my ears.

“Selby, say something,” I whisper.

Another whimper—louder, but only by degrees.

“Charlie, she’s here. She’s alive.”

“Okay,” Charlie says. “Okay. I’m going to try to make my way over to you.”

“My stomach . . . ,” Selby moans.

I try to resist a memory of the knife plunging into her. “Don’t move,” I say. “Just don’t move—we’ll come to you.”

Panic whirlpools in my torso, twisting every organ inside me to the south. I discover that teeth really do chatter if you’re scared enough. Mine clack rapidly as ice water replaces the blood in my veins. Selby’s bleeding, we’re all effectively blinded, and we’re trapped in here. Trapped, with what remains of them . . .

No, I tell myself. No, Abigail. You can’t lose it. Work the problem. You lose it now, in here, and you die.

Death in here would not be a good way to go. Less painful than crucifixion or being drawn and quartered, sure, but the darkness . . .

Every moment we swim in it, I feel myself getting closer to terror and insanity. Buried alive. We’d likely die from dehydration. That would be the official cause. Not that anyone would ever find us. Dying of thirst will take two or three days. Two or three days to die.

But the darkness.

The hope that somehow, miraculously, we can inch our way in the pitch black to find the cave entrance, the way we came in, and be free . . . but that hope is the worst part. Outside, we’d still die from lack of water, but we’d die with the sun or stars overhead, and fresh air in our lungs.

But the darkness . . .

“Stay where you are,” Charlie says from some nebulous place in the black. “Keep talking. I’ll make my way to you.”

“The pit,” I stutter through my quaking teeth. “You’ll fall in.”

“I’ll go slow.”

We can’t have been in this chamber of the cave for very long, yet an eternity has passed since we found them.

Them . . . still in here with us . . .

Stop, stop, stop, I tell myself. They’re destroyed, they’re dead, they can’t hurt you.

But they were dead before we got here, and that didn’t stop them. They’re still in here with us, still close enough to reach out, grab an ankle, a wrist, a throat . . .

No! Stay calm, Abby. Stay calm. Work the problem. Work the—

“The camera,” I say.

I hear Charlie stop his slow slide across the gravel floor. “Huh?”

“Do you have it? Is it working?”

Selby whispers, “I wanna go home.”

I ignore her. I hate to do it, but have to. “The viewfinder. If the camera’s working, open the viewfinder. It’ll be light. Not much, but something.”

Charlie makes a sound in the darkness, like a sigh of realization. I hear more scuffling.

“Go slow,” I say.

“Right.”

Time goes blank again. Now that I’ve oriented my ears toward Selby, I can hear her breathing. Shallow, rapid, and very much like my own.

But I haven’t been stabbed in the gut.

“Hang in there, Sells,” I say. Then I realize I’ve used Alex’s nickname for her, and hold my breath. Will it push Selby over the edge? Is there an edge for us anymore, after what we’ve seen? What we’ve done?

“Got it,” Charlie says with a relieved, exultant note in his voice. In the underwater muffle of the darkness, I feel more than hear the electronic whine of the camera booting up.

Please, I beg, unaware that perhaps I might actually be praying and not caring if it’s ironic or not. Please just let it work. Just that tiny blue square of light, please, please, without light I will go crazy, I will go insane if I’m not already, because insanity pales in comparison to this all being real.

Gray-blue light appears, no more than ten feet from me; tiny and pathetic in the black, yet offering hope like the sun.

“Thank you,” I say softly, but not to Charlie. The taut skin of his face glows in the light. He was so handsome two days ago. Confident and relaxed. Now, fear draws tight lines down his features, distorting his good looks.

Charlie slowly slides to me, pointing the viewfinder at the cave floor to make sure he doesn’t slip into the pit in the center of the cavern. I don’t know how long it takes; maybe a minute, maybe a year. Maybe eternity. When he reaches me, he sets the camera down carefully before surrounding me with his arms. I can feel by the strength and weakness in his embrace that he is as grateful for the contact as I am. Warm, living, human flesh. We bury our heads into each other’s shoulders, trembling.

“Okay,” Charlie breathes. “I have to get Selby.”

“I’m coming with you.”

Staying close, we tell Selby to start talking so we can get to her.

“Selby, come on,” I urge. “Please, you have to talk so we—”

“Hydrogen,” Selby says at last. “Helium. Lithium. Beryllium.”

Charlie and I look at each other, and seem to realize at the same time what she’s reciting: the periodic table of elements, by order of atomic weight. Selby and I are both sixteen, yet she sounds infinitely younger right then. Or maybe I just feel immeasurably older.

We slide toward the sound of her voice. “Boron. Carbon. Nitrogen.”

“We’re coming, Sells.”

“Oxygen. Fluorine. Neon.”

“Almost there,” Charlie says. “We’re almost there; keep talking.”

“Sodium. Magnesium. Aluminum.”

“I hear you. We’re getting closer.”

“Silicon. Phosphorus. Sulfur . . .”

Finally, we see her. Selby sits against one of the cavern walls, curled into an upright ball, squeezing her knees to her chest and shivering, both hands pressed against her side. A far cry from the militant teen scientist I met two days ago.

Selby reaches out as we near, and the three of us huddle close together. Maybe crying, I don’t know. I hope not. We need to retain the water.

“Wanna go home,” Selby says into our cluster. “I wanna go home.”

“We are,” I say, sounding much more confident than I would have thought possible. “Let’s get to the bags, see what we’ve still got left, and we’ll work our way out of here. Okay?”

I think Selby nods, but can’t tell in the grim, cold light from the viewfinder.

“How’s your stomach?” I ask.

“Uh, stabbed, thanks.”

I take her tone as a good sign. “Okay. Do you have your lighter?”

I can still smell cigarette smoke on her clothes from before we entered the cave. How long ago? How long now?

Selby pulls a small pink cigarette lighter from her hip pocket. She winces as she does it, keeping her other hand pressed against her side where the blade went in.

“How much battery in the camera?” I ask Charlie. Now that we’re together and have at least a few square inches of light, the urge to run hard and fast from the cavern is overwhelming.

“There’s one bar. So not much.”

“We better hurry, then. But careful.”

Selby’s lighter and the dim glow from the camera don’t offer much light, and neither will last too long anyway. I don’t honestly think we’ll have sufficient illumination for enough time to navigate our way back out of this godforsaken labyrinth. Yet we can’t rush, either. Rushing might get us killed. We’ve already lost one person on this trip. One, and so many more.

Which brings up a question. “What about . . . them?”

Charlie and Selby both give me shocked looks. Charlie says, “We can’t . . . We’re not bringing them out. No.”

“Okay. Just wanted to make sure we agreed on that. Let’s go.”

We scoot back the way we had come, toward our equipment bags.

The news isn’t good when we reach them, but could be worse. Some of our stuff fell in the pit when it opened up. Left over in the camera bag, we find two full batteries for the camera, Charlie’s iPhone with about half its life left, and three bottles of water. Since we didn’t have to do much climbing into the cave—we never even needed ropes—this might be enough light and water to get us out. It just might.

It also just might not. If we lose all sources of light between here and the entrance to the cave, we won’t find our way out. We will not. That’s the math.

We spent almost eight hours hiking to get this far, to get to where the pit opened up. We had flashlights and headlamps, moving at a careful pace with breaks and food. To find our way out with a viewfinder, a cell phone, and a lighter will take much, much longer.

Not to mention whatever will be waiting for us outside if we even make it.

The three of us stand together, with me helping Selby up. We stare up the steep incline that will take us to the first leg of our escape.

“What if they’re waiting for us?” Selby whispers. “What if those things are just waiting for us to show up?”

“We don’t have any choice,” I say. “We can’t stay here.”

Instinctively, I cast a nervous glance over my shoulder, waiting for the dead to spring back to life.

Again.

But they don’t. Everything is silent.

“Okay,” Charlie says, adjusting the bag over his shoulder. “Nice and easy.”

He takes one last glance behind us in the darkness, as if he can spy Alex. Even though he can’t possibly see him, Charlie whispers, “I’m sorry, man. Love ya.”

I consider saying something too, but the darkness is too oppressive, and I can’t think. We start hiking up the incline, needing to use our hands as much as our feet, not knowing what the world will be like if we find the entrance. We may wish we’d stayed in the dark and died.

Part of me wants to run through the cave. I’m able to shove the instinct down, but it’s not easy. Another part of me wants to crawl, because it would be so much safer. We end up splitting the difference, staying on our feet, walking close together, supporting each other over dry gravel that’s as slippery as water.

I noticed the dryness of the cave as soon as we entered. Even as we went deeper and farther into the labyrinth, following the signs and symbols in Charlie’s dad’s book, we found no water. Now, as we shuffle along the floor of the cave using the dim light from the viewfinder, I start wishing for a distant dripping sound. Something other than the sound of our breathing, our shoes in the dirt, the thunder of our hearts. Hearts that I’m sure can’t take much more stress.

“Oh, God,” Charlie says softly.

My impulse is to ask, What? but I figure it out almost as soon as he says it.

At our feet, off to one side, a boulder has been crushed. Crushed to powder and pebbles, like nothing more than chalk. I remember passing the round rock about as tall as a coffee table, right before we’d reached the slope we’d just hiked. It would take a team of men with sledgehammers and jackhammers to put that rock into its current pulverized state.

“It was stepped on,” I say.

We don’t stop to examine it.

Without discussing, we start to move faster. I try not to imagine we are being followed by anything alive or dead.

God, what have I done. . . .

Now I want to watch jaws!