Halloween Haunts: Warm Regards from the Meatgrinder by Mark Onspaugh

All good ghost storytellers  know that, if you want to make your story truly effective, turn down the lights.

know that, if you want to make your story truly effective, turn down the lights.

But if you really want to crank up the gooseflesh, tell it by candlelight… or, better yet, firelight.

When I was a kid, our Boy Scout troop would spend a week to ten days in the mountains at summer camp. The camp was in the woods, on the shores of a lake. It wasn’t Crystal Lake, mind you, but I’ll bet Jason Voorhees first stirred in the terror of a kid at summer camp.

Halloween is one of those festivals or events built around the coming of winter, when the days are growing short and the barriers between our world and that of the dead (or ghosts, or demons) is “thin.” Things get through, and our literature is full of tales of humans crossing over into the Land of Faerie or ghosts, or dreadful things entering our world to wreak havoc.

Long nights around a fire with little else to do, our ancestors told stories that were part cautionary tale and part thrill of the dread unknown.

I will tell you, you can really get in touch with your Pleistocene past sitting around a campfire with your friends, all eleven years old and far from home. The trees seem to close in around you, and the night is filled with a thousand things that would love to make a meal of a kid. The wind whistling through the trees, the snap of a twig – any of it could signal your doom.

The fire offers protection, but it only reaches so far – the Dark seems to gather around its edges, hoping to find a way in. And firelight is not the sterile light of Edison. Fire is alive, it moves and dances. It creates shadows and animates everything.

Is that a gnarled man with a hideous grin and long, claw-like hands?

No, that’s just a tree, you tell yourself.

Is it? Is it?

Of course, these are young kids far from home, some away for the first time ever. It’s not all ghost stories and terror. Cameraderie is celebrated, songs are sung, funny skits are presented. Some grown-up may impart an anecdote or lesson about those days in the distant and inexplicable past when he was a kid.

But there is always a ghost story.

And, as the years go by and the song lyrics fade, and the punchline of the skit is half-remembered, the ghost story lingers.

It’s in our DNA, I think, from those early humans huddled together, their teeth and nails little match for the things outside their circle, their new brains finding terror in shadows and thunder.

So they told stories, and passed them on.

In such tales we give our fear form and, if not conquer it, share it.

You’re not alone, the stories say: We’re ALL scared of the dark.

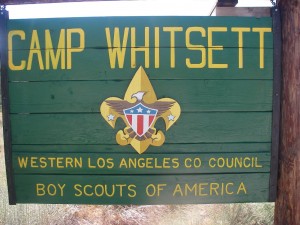

My first year at camp was at a place called Camp Whitsett, on Shaver Lake in the Sequoia National Forest. My friends and I had done some overnight camping at local parks as Cub Scouts, but this was a big deal. Almost three hundred miles from home with no TV (no computers and what-not in those days, kids). No parents, no brothers or sisters, just our Scout leaders and the Great Unknown.

The main campfire was great – songs, skits, stories – we were having a great time.

Then, one of the leaders came forward, his face grave.

He told us that it was best not to wander off alone. Scouts had disappeared in those parts, and had ended up dead… Killed by a huge man… at least, they thought it was a man. A man with a pronounced limp. He’s been killing for years, and has never been caught.

Of course, the punchline was that our storyteller walked away from the fire with a limp.

But that “twist,” that’s not what impressed us.

It was the condition the bodies were in when they were found.

He said they looked like they had gone through a meat grinder. Most of us had never even seen a meat grinder, but we had a pretty good idea what one would do to you.

So that’s what we called this particular bogey man: The Meatgrinder.

There was no vote, no discussion. If our storyteller had given a name to the phantom, no one remembered it.

He was The Meatgrinder.

Back at our tent, the cold dark just outside, we all bravely suggested what we would do if we ran into “that ol’ Meatgrinder.” Dispatching him with pocket knives or Scout axes quickly devolved into more complicated (and, to us, hilarious) methods of disposal – I believe the height of which was “setting fire to his privates after dousing them with lighter fluid.”

Hey, we were eleven.

By then, we were all feeling quite brave and the fear was gone.

The Meatgrinder was no match for us!

Then came the screaming.

Somewhere, close by, one of our friends shrieked as if he were being torn apart.

I will tell you, I don’t think I have ever again been as afraid as I was at that moment. I was paralyzed in my sleeping bag – as were all my tent mates.

Thoughts of helping my friend never entered my mind.

Fighting off the monster? No way.

I just lay there, praying it wouldn’t get me.

It was a set-up, of course, one of our friends coaxed into screaming by our leaders. Rumors sprang up for a short time, people claiming to have seen a giant, limping hulk carry off one of our friends, only to drop him before grinding him into paste.

Camp ended, and we went back to the civilized suburbs.

In years to come, I would do my own campfire storytelling, embellishing my stories with undead Nazis, living skeletons and the occasional Wendigo. I learned that telling scary stories was as much fun as hearing them.

But I never forgot The Meatgrinder.

Now, every time I consider a Halloween costume, or craft a horror story, I know he’s there, deep in the shadows of my imagination, and he’s smiling.

And it is a terrible smile.

TODAY’S GIVEAWAY: Mark is offering one copy, winner’s choice, of either his collection CHRISTMAS GHOST STORIES or his zombie novel THE THETIS PLAGUE. Comment below to enter or e-mail membership@horror.org with “HH Entry” in the subject line.

MARK ONSPAUGH is a California native and the author of over fifty published short stories. Like many writers, he is perpetually curious, having studied psychology at UCLA, exotic animals at Moorpark College’s Exotic Animal Training & Management program, improv comedy with the Groundlings and special effects makeup with several of the industry’s top makeup artists. Mark has also written for film and television, including the script KILL KATIE MALONE. His first novel THE FACELESS ONE was published by Random House under their new Hydra imprint. He is working on a standalone novel in the same universe entitled GREEN WATER, also for Random House/Hydra. His zombie novel THE THETIS PLAGUE was published by Severed Press; and he is currently at work on a kaiju novel for the same publisher.

MARK ONSPAUGH is a California native and the author of over fifty published short stories. Like many writers, he is perpetually curious, having studied psychology at UCLA, exotic animals at Moorpark College’s Exotic Animal Training & Management program, improv comedy with the Groundlings and special effects makeup with several of the industry’s top makeup artists. Mark has also written for film and television, including the script KILL KATIE MALONE. His first novel THE FACELESS ONE was published by Random House under their new Hydra imprint. He is working on a standalone novel in the same universe entitled GREEN WATER, also for Random House/Hydra. His zombie novel THE THETIS PLAGUE was published by Severed Press; and he is currently at work on a kaiju novel for the same publisher.

Read an excerpt from The Faceless One by Mark Onspaugh

Prologue

Alaska, 1948

The little boy was already up and dressed when his uncle came for him. His mother had told him to go to bed early, but he had been too excited to sleep. She set up the coffeepot before going to bed, but he stoked the fire himself and put it on to brew. Then he had carefully dragged a chair over to the cabinet and replaced the pristine white mug his mother had left out for the chipped blue one his uncle favored.

Jimmy Kalmaku was pouring the coffee as the old truck pulled up. The strong aroma filled the kitchen, reminding him of early mornings when his father and uncle would go out in the boats.

He listened for his uncle, but of course he made no sound. Despite the silence, the little boy opened the door just as the old man reached the threshold, the bond between them as strong as new rope. Uncle Will entered and took the coffee. Breathing it in, he nodded his approval. Then he took the pot and poured a cup for Jimmy; he gave the boy the strong brew, heavily laced with cream and sugar. The mixture was bitter and sweet, and Jimmy felt very grown-up drinking it. He was seven years old in that spring of 1948.

The two left the warmth of the dark house, their boots crunching over the frost-covered earth. Boley rose and stretched stiffly on his haunches. Although dogs often went with the men on fishing trips, Boley would not be joining them. Jimmy patted the dog, and Boley looked up into his face with sad, wise eyes. Ever obedient, the dog did not bark as they got into the truck and drove off.

As they traveled toward town, neither spoke. Familiar with his uncle’s ways, the boy silently watched his world pass by, its familiarity stripped away by the earliness of the hour.

Their village was located in the lowlands along the Gulf of Alaska and was called Yanut. It was about ten miles from Yakutat and small even by Tlingit standards. The town proper was barely two blocks long, enough space to keep a grocer, a drugstore, a hotel, a hardware store, and three bars. The bars—the Northern Lights, the Yanut Bar & Grille, and the Blue Lantern—were always busy. To Jimmy, they always looked mysterious and inviting, with their bright neon and shadowy figures hunched within, smoke and music floating out into the crisp night air like wraiths.

Now even these islands of light and noise were dark and silent, their patrons sleeping off another Friday night.

Outside the hotel, a shadow sat in one of the metal chairs, illuminated only by the orange glow of a cigarette. The glow intensified as they passed, and the boy felt his skin ripple with gooseflesh. Who else would be up if not a demon? Perhaps it was the Stick Man, waiting for some little boy who should be home in bed . . .

“Guess old Charlie can’t sleep,” his uncle Will said, answering the boy’s fear without calling attention to it. Jimmy relaxed at the familiar name, not realizing he had tensed as tight as a bowstring, the fingers of his right hand anxiously gripping the dashboard.

The rest of the village and its outlying homes were quiet, peaceful in the waning light of the moon and the stars, the pines tall sentinels in black and silver. For the first time in his short life, Jimmy looked at his hometown and found it beautiful. He smiled as he thought of the people sleeping in their beds, like his own family. He felt the cold of the window against his forehead and was happy.

Uncle Will’s wife had made them some corn bread and dried fish, and Jimmy munched on his breakfast as they drove away from town. The last homes and shacks gave way to thick stands of pine, their scent a constant reminder of Tlingit ties to land and sea.

Jimmy was surprised when his uncle turned right as they left town. Left would have taken them down to the bay, where the boat Uncle Will had supposedly hired would be waiting. To their right lay a deep forest of Sitka spruce, hemlock, and cedar, and beyond that a glacial waste.

Jimmy had studied under his uncle for two years and knew there was a time for questions. This was not it. When he kept his tongue as they turned the wrong way, his uncle nodded in satisfaction.

By the time the sun was just edging over the mountains to the east, Uncle Will arrived at a small road that was little more than a dirt trail. He turned onto the side road and the truck bounced over stones and ruts for over an hour. Now Jimmy wished he had not been so greedy with Aunt Mo’s corn bread. His stomach squirmed as he held on to the dashboard and tried to think calming thoughts.

Uncle Will finally stopped when the road became impassable with snow. In this region, the drifts stayed in place even in summer. Jimmy had never ventured so far from home and was both elated and terrified by the strange surroundings.

Uncle Will got out of the truck and motioned for the boy to do the same.

“Remember our path today, Mouse, and observe everything. I hope you need never come this way again, but you must remember.”

Jimmy nodded. They walked along a path strewn with snow and jagged black rock. The air was still and crystalline, as if it might fracture into bright blue shards at any moment. The sun brought light, but little warmth. Jimmy was glad his mother had made him such a thick coat. He stuffed his hands in the large pockets and followed his uncle off the path.

Uncle Will was sixty-seven years old, and his gray hair hung down to the small of his back in several plaits. Were he performing an important ritual, he would let it hang long and unkempt as he worked his magic. The old man’s features were as weathered and polished as stone, his eyes as dark and clever as Raven’s. Half of his left ear had been torn off in an encounter with a bear, and the ragged remnant marked him as one particularly powerful. He wore a large earring of obsidian and copper punched through the partial arc of cartilage the bear had not removed. Uncle Will rarely smiled, but on those occasions when he did, it was usually in the company of his nephew. As for Jimmy, he loved his uncle and was in awe of him.

By ten o’clock, they had reached a rocky outcropping. In winter, the stones would be hidden under high drifts, but now they poked up from the snow like the dorsal plates of some prehistoric beast.

As Jimmy approached the rocks, a feeling of disquiet came over him. His skin tingled, and there was a fluttering in his stomach, as if he were about to jump off a high ledge into unknown waters.

There was a cave on the far side of the outcropping, its entrance only three feet high. Several small talismans of carved ivory had been placed at the entrance, their magic keeping them in place through years of snow and thaw, rains and wind. The skeletons of several birds lay near the entrance, as well as remains of a hare and the desiccated body of a fox. All of the creatures pointed away from the mouth of the cave, as if they had blundered in, then died as they exited.

Jimmy looked at the remains, fear growing in him. He prayed fervently that his uncle would tell him some story, then they would be on their way.

His uncle removed a flask from his coat and told him to take a small sip.

Jimmy’s nose wrinkled at the pungent smell of the flask, and he took a tiny, tentative sip. It tasted like smoke and burned his throat. He coughed in loud and rasping hacks as his uncle retrieved the flask. Jimmy then felt a sudden burst of warmth in his belly, and he felt alert, strong.

His uncle clasped his small shoulders.

“One day,” he said, his voice low and full of gravity, “I will be gone, and our people will look to you. You will heal the sick and guide fish to the hooks and nets. You will cast out spirits and find those lost on the ice. But nothing, nothing you learn from me will ever be as important as what I show you today. Keep it with you always and never forget. Do you understand?”

Jimmy nodded, more out of fear than understanding.

His uncle pointed to the mouth of the cave, his expression grave. Jimmy looked at him for a moment, then realized his uncle wanted him to go in alone. He started to pull back, but his uncle gripped him fiercely. Jimmy whimpered, but there was a terrible fire in his uncle’s eyes.

“I cannot take you, you must see alone.”

Jimmy fought his desire to run away, thought it seemed preferable to be lost in these trackless wastes or ravaged by a bear than see what lay beyond the diminutive, carved sentries and their collection of unwitting sacrifices.

“You are my nephew, Mouse, and you are stronger than you realize. Our people will depend on you—this is not a duty you can shrug off like a wet coat. You must see. You must understand.”

Jimmy looked in Uncle Will’s eyes and saw the fierce love that his uncle had for him. He realized that he would do almost anything save disappoint the old man. Slowly, he nodded.

His uncle clapped him on the back, a gesture among adults, and the hard blow seemed to strengthen rather than pain him. Taking a breath, he stooped slightly and entered the cave.

Inside, it seemed warm rather than cool, and the air was redolent with the scents of cinnamon and leather, the smells of the long dead. The floor was rough and jagged, heading down in a gentle slope. Along the walls were dozens of skulls, both animal and human, each one painted and decorated with beadwork or feathers. Beast and man, they were grouped together, as if they had been allies in some great conflict. The boy knew enough to recognize that these were not trophies but sentinels from the Land of the Dead, guardians from across the seas that had been entrusted with some sacred task. Indeed, the air was heavy with decades of ritual and ceremony. Although he was frightened, he dared not utter a sound, lest those hollow eyes turn on him.

As he moved down, the light from outside faded, and the air turned chill, a frigid cold that increased in severity, a cruel and icy state without respite. The skulls along the wall became more massive, some of them with fangs nearly a foot long, cruel scimitars in predatory jaws. Just as the light all but disappeared, he saw massive skulls with huge, curving tusks as large as himself. Inverted, their great ivory arcs formed a portal. There was a dim light ahead, and he made for it, conscious of the grinning skulls flanking his progress, their empty eyes retaining the visions of millennia past.

Jimmy Kalmaku was filled with both terror and exhilaration. He knew that what he was about to see was only for the most wise.

He stepped into a vast chamber; its walls covered with ice colored a deep blue by the centuries. Long ago the cave had been a dwelling, and a vent had been laboriously carved in the ceiling for the fire pit. This makeshift chimney served as a sort of skylight, allowing the spring sun to partially illuminate the chamber.

To his left, the walls were bare. There were no skulls, no carvings, no painted figures or masks. To his right, a wall of ice, the light from above illuminating it, its interior filled with a soft, golden glow. Rather than smelling musty, there was a clean smell to the place, and the hint of spice like his mother sometimes used in cooking.

In the center, obscured and distorted by thick blue ice, something was suspended.

It was very dark and roughly circular. The object looked to be about the size of a large dinner plate, but it was hard to tell given the distortion of the ice. As he tried to puzzle out what it was, he saw a glimmer of gold around its outer edge.

Suddenly, it saw him.

There was no change in the object, no opening of eyes or shifting of position. It remained suspended in the ice as it surely had for hundreds of years. But he knew it saw him. He knew with absolute certainty that it was hungry for him, jealous of his life and warmth.

hello, boy

Jimmy stared at it. The voice was in his head and all around him.

are you cold? i am cold

It was the sound of gusts around their roof at night, when the wind scrabbles and claws at the eaves, searching for a way into the snug, warm room. It was the sound a man makes when he is trapped under thick ice, his fellows above watching helplessly as he is claimed by the cold sea.

let me out

The voice seemed to tear into him with needlelike claws. He backed up, striking the opposite wall and letting out a strangled gasp.

let me out

The voice was sliding around his mind, an eel that left a viscous and foul-smelling ooze on his thoughts. Jimmy felt at any moment he might throw up or faint.

let me out, jimmy. i can teach you more than the old man

At the mention of his name, a low moan escaped him. It knew him. Now he would never be free of it. No matter where he went, it would find him.

let me out

Would that be so terrible? To let it out? Perhaps it was a mistake, imprisoning it here. What creature deserved such a lonely and terrible existence? He could dig it out with tusks from the animal skulls, and he had the knife his uncle had given him . . .

“Tread lightly, Mouse.”

It was the voice of his uncle, deep in his mind, and it brought both comfort and sanity. It lifted the thick veil that seemed to have wrapped his mind and heart only seconds before.

He shook his head, trying to clear it further. The ice before him seemed to thrum with the power of the thing. If he were to let it out, what terrible things might be unleashed? His uncle said he must not forget what was here, that he must protect their people. It belonged here, shrouded in ice and shut away from the lives of Men.

Let Me Out

It was growing angry now, realizing its hold on him was weakening.

LET ME OUT

Its voice rose to a scream in his head, a sound that seemed to strike the ice like a mallet.

Jimmy ran then, unable to control himself. He blundered into one of the large skulls outside the chamber and opened a gash on his forehead. Disoriented, he started down a side tunnel, into the darkness. The screaming continued inside his head, followed by laughter that seemed to promise an eternity of misery, a suffering beyond anything he could imagine.

Feeling hopelessly lost, he collapsed on the stone floor and wept, knowing he would never see his mother or father again. The young boy prayed for death, prayed for anything that might bring silence.

Something pricked the back of his right hand, and the sharp pain made him look up, sure the thing had found him.

A raven, as white as the first snow of winter, regarded him quizzically. It hopped up, then pecked at his hand again, more gently this time. He could still hear the screaming of the thing in the chamber, but it seemed distant now, a wolf that circles the village long house in vain but cannot enter.

The raven hopped away from him, and he could see now that the tips of its feathers and beak were a burnished gold. It was the most beautiful thing he had ever seen. It moved away from him, slightly luminous in the dark side tunnel.

Jimmy followed it, and it led him quickly past the skull sentries and to the tunnel leading up to the cave entrance. The screaming of the thing in the chamber had diminished to little more than a whisper, and he shut it out of his head with thoughts of his mother’s smile and his father’s carrying him on his broad shoulders through town.

When he reached the entrance, he looked for the raven, but it had disappeared. He stepped out into the sunlight, and its warmth was like a welcome caress.

His uncle hugged him, then dressed the wound on his forehead before they made the hike back to the truck.

He wondered if his uncle would have come after him if the raven had not. Then he wondered if his uncle had sent the raven, if, indeed, he had been the raven. He had many questions, but they could wait.

“Tell me about the thing in the cave,” Jimmy Kalmaku said.

As they drove back to the village of Yanut, his uncle told him about The Faceless One.

Chapter 1

New York, the Present

Daniel put down the sandwich and listened.

He was sure he had heard something. He picked up the remote and muted the television. The comedian on-screen gesticulated silently as Daniel strained to hear.

There was a slight rustle behind him, and he jumped.

The sound had come from the entryway.

Slowly, he rose from the chair and made his way cautiously to the front door.

All was quiet. It was Sunday morning, and most of the other tenants were out.

Daniel listened at the door. Warily, he reached toward it, his fingers splayed and quivering. He put them gently against the door, as if trying to divine something.

All was quiet.

He knelt to the delivery caddy. It was a revolving drum he had installed next to the front door six months ago. A deliveryman would put his groceries in the drum on the hall side. Once he was gone, Daniel could rotate the drum and retrieve his delivery. The opening on his side was secured with a massive lock and heavy mesh, its openings no more than a millimeter square. Daniel unlocked and turned the crank. He leaned back as he did so, still not sure whether something might be strong enough to tear through the steel mesh.

Or small enough to fit through it.

The drum slowly turned, and a bag of groceries appeared, slightly listing. The delivery boy had either forgotten to ring the bell, or Daniel had missed it while he was in the shower. As he breathed a sigh of relief, a can near the top tumbled out, and the resultant thump startled him again.

He chided himself for being so jumpy. He had been extremely careful and taken numerous precautions. Besides, he was beginning to doubt they could travel this far.

Still, he checked the mortar along the bottom of the door. It was as white and pristine as the day he had mixed it, sealing the door with careful application of brush and trowel. He ran his finger along the smooth expanse. It felt cool, comforting. He removed the combination lock from the mesh cage and retrieved his groceries, shaking his head as he put the can of tuna back into the bag. He relocked the cage and spun the drum back into position.

Daniel set the groceries on the counter. Truth be told, he had enough food for another three months, but he liked fresh lettuce for salads and had been craving tuna. He put the perishables away in the large double refrigerator and put all but one can of tuna into the spare bedroom he had converted into a pantry and storage area.

He washed up in the bathroom, setting his glasses carefully on the sink. His face looked a bit gaunt, and that was due to anxiety and lack of sleep.

He brushed his hair back and retied his ponytail. His dark hair was really starting to look shaggy, but there was no way to get it cut. If his self-imposed imprisonment was going to last, he might have to teach himself how to cut his own hair.

Daniel carefully retrieved his glasses, then wiped up the water spots around the sink. He kept the place spotless—except for the tree, of course.

Returning to the kitchen, he thought of continuing his sandwich-and-television break, but he was too unsettled to enjoy either. He wrapped the sandwich in a paper towel and stuck it in the fridge. He tried to keep waste to a minimum. Whatever he couldn’t reuse or flush down the toilet, he left in a bag in his delivery caddy. He paid a kid down the hall ten bucks a week to take his trash down for him.

Daniel looked over at the niche that contained his computer, laser printer, various reference books, and journals. The computer was a godsend, one of the things that allowed him to live comfortably—or at least safely—in exile. He paid all his bills over the Net and conducted all his research from there. He made a mental note to order more print cartridges before his eyes continued up over the desk itself.

The fetish was still there.

It revolved slowly on the forty-pound test line he had hung it on, the breeze from the central air causing it to survey the room with bright, obsidian eyes.

Daniel honestly didn’t know if the fetishes were keeping him safe. Still, he was not going to test the efficacy of his charms. They had taken a lot of work, and the two of the essential ingredients were both costly and illegal.

Thinking back on those feverish, sleepless nights when he had crafted the effigies and invoked the protective sphere, Daniel hurriedly went to each window of his Fifth Avenue town house. On the outside of each window was a similar effigy, sealed there with a permanent epoxy. The building’s window washer was paid an extra fifty dollars to clean carefully around each one.

Each fetish was in place, its eyes glinting outward, its mouth exposing an imposing set of reddened teeth.

All was quiet.

Daniel once again chided himself and decided perhaps he’d rest a bit more before getting back to his research. Maxwell at UCLA had just published a paper that might be relevant, and the search engine he used had indicated a new Web page out of China that might help him, once he got it translated.

He crossed the rich cream carpet, now stained in one corner from the fabrication of the fetishes. If he ever got out of the place, he was going to have that carpet replaced. Hell, he might even move. He hadn’t seen Steven in a long time, and his brother kept telling him to leave “that hellhole,” which is how he always referred to Manhattan, and join him in California.

Countless times he had wanted to call Steven, but he knew his brother might think him crazy, might even come to help him, and he couldn’t risk that. What would happen to his own flesh and blood if he were outside the sphere of protection Daniel had conjured? Hell, he hadn’t even uttered Steven’s name, lest it give the thing power over his kid brother.

If he was were able to complete his research, then everyone would be safe.

Tell that to Milo Grant and the rest of the village, he thought.

He had read the news the day before. He had been trying to track down the shaman and still had no leads. He had Googled Yanut and been shocked to see what had become of it. Maybe Tully was right, maybe he was a “thief and a damn fool,” but what choice did he have?

The phone rang, and he let the service pick up, sure it was Tully or any other of his colleagues who were either curious or pissed off. Once he was able to venture outside, he’d have a lot of explaining to do.

Their gloved hands carefully chipping the ice. Milo grinning, his uneven teeth glinting in the reflected light. Had he died screaming?

Crossing the room, he brushed against the Christmas tree. A cloud of needles fell whisper-soft to join the ring of debris on the carpet. He had sealed the place before he had remembered it. So it stood in the center of the living room, its once-green needles a dull brown, its bright metallic and glass ornaments slowly gathering dust. He had left it as a testament to his stupidity and the lack of planning that had landed him in this prison. The ornaments tinkled slightly as he passed, as if announcing an arrival.

There was another sound then, a sort of low crackling coupled with a barely audible squeal.

Daniel turned to the windows overlooking Central Park.

One of the fetishes was coming loose from the window, sliding slowly down the glass, like a slug making its way across a clear expanse.

The epoxy had been expensive and guaranteed to hold for at least ten years. It was impossible that it was giving way as if it had no more adhesive strength than chewing gum, yet the fetish continued its slow and torturous progress down the pane of glass.

Daniel rushed to the window, but what could he do? He couldn’t risk opening the window. He stood there, powerless, as the small figure came loose and fell away.

He craned his neck as the effigy fell two stories to the street. It came to rest just under a large maple tree. Perhaps he could call the doorman, have him retrieve it. If he was quick, he could reapply it to the window, saying the invocation before opening the window.

His neighbor’s kid, Mitchell Price, rode up to the effigy on his new bicycle, one he had largely paid for himself after emptying Daniel’s trash for six months.

He looked at the fetish intently, then looked up at Daniel.

Daniel calmed himself and gestured that the boy should bring the idol up to him.

Smiling up at him innocently, Mitchell Price slowly rolled the front wheel of his bike over the effigy, crushing it.

Daniel watched in horror as an ochre stain began to spread from the fetish.

Mitchell looked down and made a disgusted face but rolled the front tire of his new bike over the protective effigy again and again. Its obsidian eyes fell away, and its fierce teeth cracked under the weight of the bike. With each pass, Mitchell would look up at Daniel to see his reaction.

Daniel stood there, paralyzed, as a line of his defense was demolished by a child.

The boy continued until the effigy was no more than a collection of rags and thread, gristle and pine needles. The ochre fluid was absorbed into the dirt surrounding the maple tree, which would be dead within a week.

Then Mitchell looked up at him, smiled sweetly, and rode away.

Daniel stepped back from the window, as if he expected something large and dark to crash through the glass. He stumbled against his chair and fell down hard, his teeth coming together with a loud crack.

Nothing came through the window. Outside, the leaves of the maple tree nodded lazily in a summer breeze. The air conditioner and the computer continued their low purring.

Daniel flopped back on the floor, his eyes filling with tears. Six months of this had worn him to a frazzle. All for nothing, it seemed. A protective device had been destroyed, and both he and his home were intact.

Perhaps they couldn’t travel this far. Perhaps Duvall had been right. It wouldn’t do to be overconfident, though. Perhaps he would take an exploratory walk out onto the landing. He could always run back in at the slightest sign of trouble.

The thought of breathing air that wasn’t recirculated was a heady one, indeed. He wanted great drafts of it, air chilled and filled with pine, or hot and redolent of sage and mesquite. Perhaps his days of captivity, of exile, were over.

The archaeologist leaves his tomb at last.

In answer to this small note of hope, he heard a slight scratching and the barest suggestion of a whisper.

He got up, his heart hammering in his chest.

The scratching became louder, as if his thundering heart had been construed as a welcome.

Daniel crossed the living room toward the front door, that genial distance seeming to stretch out miles before him.

There were small bits of mortar on the floor before the large oak door. As he watched, several more grains fell away from the strip sealing the door.

Something was trying to dig its way in, using claws or teeth to reach him.

I only touched it once, he thought. Just the tip of my finger. It was so beautiful, so terrible. I had to touch it just once before it was crated and shipped. Just once.

Daniel hurried to the computer and brought up his e-mail page. He had drafted a letter to Steven long ago, in case something like this ever happened. He tried to bring up the draft, but he was nervous, hitting icons for mail already sent and files on correspondence from his colleagues at the university.

In his panic, he brought up the letter and promptly deleted it. Quickly, he composed a new letter, trying in a few sentences to explain what had happened and what Steven must do.

A scent of cloves reached him, overlaid with smells of iron, copper, and pine.

He looked behind him.

From his vantage point, he could see the wall near his chair before the television but not the chair itself.

There was a shadow on the wall.

Something was sitting in his chair.

With great effort, he turned to the computer and sent the message to Steven. The note winked out, and a smiling icon of an anthropomorphic envelope informed him his message had been sent.

He caught a glimpse of himself reflected in the clock mounted in his work space. He looked insane.

Something hit the front door with an angry thud.

Daniel stood slowly. He tried not to make a sound though any squeaking the chair might have made was masked by the scrabbling of something on the other side of the front door. Daniel moved quietly and peered around the corner at his chair.

It was empty.

He looked at the wall. The shadow was still there.

The shadow stood then and stretched, a gesture that was all the more horrible for its banality. It was roughly humanoid in shape, with long claws that seem to emerge and retract from the tips of its fingers, like a cat’s.

He found himself praying, which was ironic. He had published an article on the superstition of prayer just two years ago.

There was no place to run.

He ran anyway, trying to reach the bathroom.

That was when the shadow stepped off the wall and caught him, enveloping him in its embrace of cobwebs and rotting meat.

And when the door crashed inward, the things that had tracked him across so many miles covered him with their glittering eyes and snapping teeth.

So many teeth.

I’ve got your great Christmas Ghost Stories and your gripping Thetis Plague already! But I was thinking how much I’d look forward to an Onspaugh novel or story collection on Scouts, horror, and heroism. That special merit badge which only a very few of the older Scouts received in the small mountain town of Raptor, Colorado; and their troop of dedicated and specially trained Eagles…

The meatgrinder does sound like a cool bogeyman. Now I want a copy of The Faceless One.