Halloween Haunts: A Condemned Man, A Halloween Memory by Steve Rasnic Tem

Back then, for me, it was all about masks.

For Halloween, sure, but I’m also talking about day-to-day. This all started with the perception that people seldom said what they really felt about anything. I wasn’t sure why, but apparently there was something impolite about frankness, and politeness was something we took pretty seriously in my part of the South. The only person I knew whose face invariably expressed whatever passed through his head was the town’s developmentally disabled fellow who sat on a bench by the drugstore when he wasn’t out with his burlap sack collecting roadside treasures. Whether he was angry or happy or sad you could always tell by the expression–or expressions–painting his face, and so as a child I got the idea that that was one sign of brain damage–you lost your mask.

I also came to believe that success or failure in life might be measured by how one handled one’s mask. Steve McQueen, Robert Mitchum–they were born with wonderful masks, or maybe they grew them, I didn’t know for sure. But in any case they handled them brilliantly–they appeared to have that coveted ability of controlling how other people felt about them, because of their mask. I would have given anything for that. I had an extremely difficult time figuring out how other people saw me–it’s still not one of my major talents–much less knowing how one might control that perception. No one I knew had that power, although a couple of the more popular kids had a taste of it. They knew a little about handling the mask, wearing the body, saying the right things, modulating the tone, revealing just the right amount of feeling and no more. They even seemed to know the rudiments of altering that mask to fit the circumstances.

Fat kids, ugly kids, had the additional burden of a mask that rarely responded to what they wanted to project. Clearly, some masks were such that it was almost impossible to determine who was wearing them.

So putting on a mask, I thought, was a wonderful thing. If I could have gotten away with it–I think I would have worn one all the time.

I grew up in southwest Virginia, at that place where Virginia elongates into a point (a friend of mine used to say “it’s where Virginia kicks Kentucky in the ass.”) One of the poorer counties in the country. So Halloween wasn’t something you spent a lot of money on. (I remember watching a Beverly Hillbillies episode in which the trick-or-treaters at one house were given plastic Jack-o-Lanterns full of treats. I was astounded, calling my brothers in to see how they celebrate Halloween at rich people’s homes.) In our town treats were cheap candy at best, at worst hard pears from the last harvest of the year from the trees in people’s own yards–I broke a tooth or two before I learned better. You could buy a mask at the five and dime for a dollar or so–I didn’t see a full costume for sale in our town until I was almost out of high school. So every year the challenge became picking a mask that you could cobble up a matching costume for with little or no money.

Of course there were those universal costumes kids with no money (or time to spend on preparations) have made for decades: hoboes and ghosts. My brothers and I were hoboes five or six years running when we were little–carrying a stick with a kerchief full of rags tied on (My mother kept referring to it as a “bindle stiff”–I thought she was saying “bend, ‘lil sniff” which I figured was the way two smelly hoboes were supposed to greet each other, so all night long I was bending over and sniffing which must have looked quite odd.) Of course, since we were identical hoboes every year during that time and we rarely strayed far from our street everyone knew exactly who we were. “Hey, Fred–it’s them nice Rasnic boys from down the street. Drop a couple of extry pears in their pokes.”

Being a ghost was spookier, and it was harder to figure out who was under that sheet. But when the sheet shifted the eyeholes didn’t line up right and you could kill yourself tripping down semi-rural streets with few lights. One year my little brother insisted on wearing a sheet which was particularly lame since it had a big flowery border around the edges. But my other brother and I could not dissuade him, and had to take turns holding his hand so that he wouldn’t get killed. In any case my mother felt he was safer in white. We were never allowed to wear dark costumes at Halloween because of an apocryphal incident some fifteen years before when a five-year-old dressed in solid black got away from his mother, ran out in the street, and was run over by a car.

Certainly there isn’t a lot to that story but it creeped me out then and it creeps me out now. In part it is because the story was such a perfect container for my mother’s obsessive worries and fears, and in part because of a Life magazine photo from those years which I just could not get out of my head: a small shoe with a dirty sock lying on a dark highway, and nearby a woman on her knees on the pavement, her face split with a kind of grief I’d never imagined before.

Southwest Virginia was rather isolated from the rest of the world at the time. Now I realize that we didn’t have all that much, but at the time we certainly didn’t feel poor. And it felt like we lived in the safest place on the planet. What we knew about the outside world came from Life and Look and National Geographic magazines, TV sitcoms, and the CBS Evening News (Douglas Edwards when I was small, then Walter Cronkite came along when I was just beginning to realize how big the world outside those mountains must be.) The first national newscasts I have memory of were only fifteen minutes long–I remember my dad saying that it was a good length for a news program, because “that’s about all the bad news a man can take in one day.” The outside world seemed to be all about bad news.

Which isn’t to say that my friends were angels, of course. Halloween pranks could turn rather destructive, particularly out in the farm communities: trees cut down to block the roads, furniture and equipment hung from telephone poles, farm wagons hauled up on top of barn roofs (the exact mechanics of this particular prank seemingly as mysterious as the building of the pyramids), fields and brush set ablaze. Fewer parents allowed their kids to participate in trick-or-treating. Some years Halloween was practically shut down because of the pranking.

But something the outside world did have was color, and mystery, and a large number of people who had not known me all my life and would not recognize me behind a mask. The fact that a mask might work so much more effectively in that world was both exciting and terrifying. So at a certain point I started spending painful hours sewing and constructing in an attempt to make decent Halloween costumes for myself, costumes which in some twisted way reflected what I imagined of the outside world: a convict with hand-painted stripes and wounds, a two-headed snake whose narrow body was almost impossible to walk in, a succession of elaborate robots consisting of batteries and lights mounted to extremely uncomfortable cardboard boxes, “HelpMan” (my brother was “HelpBoy”) who despite his name was solely out there to cause trouble, and a variety of criminals and thieves. The best thing about all of these costumes, I thought, was that I did not feel compelled to speak with them on. Back then even saying “trick or treat” to an adult or a stranger was extremely difficult for me.

The last year I went trick-or-treating I had no intentions of going. I don’t remember exactly why–it wasn’t as if I had better things to do with my time. It seemed the rest of the world was well into the 1960s, but as far as Southwest Virginia was concerned it was still ’55 or so–my dad still had his Chevy BelAire from that year and it didn’t seem outdated in our little town. I still wore my hair in a flat top, having graduated up from a “burr” approximately two years previous (Although I had always thought of it as “Brer” because Brer Rabbit’s hair was real short on top between his ears in this storybook I’d had since childhood–it’s a wonder I ever learned English at all).

My friends had stopped going out on Halloween the previous year, but I only saw my friends at school. My brothers were going, of course, but they were going to dress up as baseball players or something equally uninteresting. I was a big kid, and I knew I was going to look weird out there begging for candy, and I would feel humiliated if anyone recognized me this year of all years, but something perverse in me suddenly wanted to go, at the last minute, a few hours before dark. It’s an affliction I have to this day–sometimes when I’m convinced I’m going to have a terrible time at some event, it makes me want to go that much more.

It was too late to think up anything special. I rummaged through my drawers and pulled out an old checked shirt, some brown corduroys worn to the shade of attic dust. I didn’t have a mask, and we were out of old sheets. I did find a foul, yellowing pillowcase on the floor of my closet. I cut three holes and slipped the thing on. It was too loose–the holes shifted around. I found a graying piece of cotton rope, and with an idiocy perhaps only another boy could appreciate I used it to tie the pillowcase to my neck. Not too tightly, of course. After all, I was thinking, I’m not an idiot. Then I was complete, a combination of two old standbys, hobo and ghost.

Just before I went out I was looking at myself in the mirror, and recognized where I’d seen this image before, in that bible of the outside world, Life magazine. With the exception that my hood had holes, it looked like what the guest of honor at a lynching might wear. I knew these things still happened, or had recently happened, in parts of the South, a South I did not know. Despite that, however, I knew there were people in my county, people with ordinary-looking faces, normal masks, who were capable of much the same. Looking in the mirror creeped me out then, which made me think that finally, this year, I had really succeeded with a costume.

Just as I expected, people were a little cold when I came to their door that year. A few even mumbled that it was a shame, a big boy like me out getting kids’ candy like that. Normally comments like that would have sent me scurrying home. But it was obvious no one could recognize me. They didn’t have a clue. I sang “Trick or treat!” sweetly, just like the little kids, at each house. And even if they were unhappy about me coming, they still gave me candy. I wasn’t sure why–I guessed it was just southern hospitality at play. I used to think that if someone came to my grandfather’s house to murder him, he’d first offer them cold milk and biscuits.

At one door a woman asked me somewhat sourly, “So what are you supposed to be?”

Without hesitation I answered, “a condemned man.” There followed a profoundly uncomfortable silence, as if she didn’t know what to say to a statement like that. I’ve received that same reaction more than a few times over the years.

Now, I didn’t know I was going to say that–it just popped out. And as I thought about it, it didn’t seem quite accurate–certainly by the time you’ve got that hood over your head and the rope around your neck you’re at least one baby step past condemned. But I still liked the sound of it, and used the phrase at least twice more that Halloween, and each time I was pretty sure the people at the door didn’t know what the hell I was talking about, which to tell the truth was a fairly liberating thing.

Then toward the end of the night I had the disorienting experience of passing by a mirror in someone’s front yard: as I was approaching the steps I passed myself coming away from the steps. Then I stopped and looked very closely, because of course there was no mirror. The other me had stopped as well to stare.

I was terrified, my skin rippling with chill, a particular form of anxiety attack I was more than pleased to grow out of a few years later (although I certainly didn’t think of it in those terms in my late adolescence–back then it was merely my skin trying to peel itself from the bone). The other me didn’t say a word, but his fists were clenched, as if he were ready to beat the mask off me.

But then he ran, and I didn’t see him again. Later I would realize that although the checkered shirt was of similar color, it wasn’t exactly the same color, and I thought the pattern might have been different. The pillowcase hood looked much the same, but the rope was brown twine, I think, rather than my gray cotton.

But he had been about my size and build, and it was simply amazing to me that anyone would have come up with that exact combination of disguise. I wondered if he, too, had called himself “a condemned man.” I wondered if he had had any better response from our neighbors behind their doors. And I wondered about what they must have been thinking, seeing two apparently identical boys, boys too big for Trick-or-Treating, wearing such odd, vaguely-disturbing outfits.

Most importantly, I hadn’t a clue who this fellow was behind the mask, and I never found out, although we had to have gone to the same school–hell, there was only the one school, and I knew everybody, absolutely everybody in it, and I couldn’t begin to guess who this could have been.

It really creeped me out. It creeps me out still.

— originally appeared in October Dreams, Cemetery Dance Publications

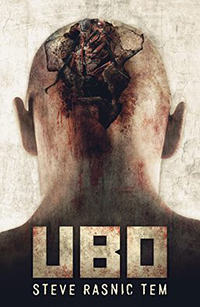

Steve Rasnic Tem’s last novel, Blood Kin (Solaris, 2014) won the Bram Stoker Award. His next novel, UBO (Solaris, January 2017) is a horrific science fictional tale about violence and its origins, featuring such historical viewpoint characters as Jack the Ripper, Stalin, and Heinrich Himmler. He is also a past winner of the World Fantasy and British Fantasy Awards. A handbook on writing, Yours To Tell: Dialogues on the Art & Practice of Writing, written with his late wife Melanie, will appear early in 2017 from Apex Books. In the Fall of 2018 Colorado-based HEX Publications will bring out his young adult Halloween novel The Mask Shop of Doctor Blaack (note that Blaack is not a typo).

Steve Rasnic Tem’s last novel, Blood Kin (Solaris, 2014) won the Bram Stoker Award. His next novel, UBO (Solaris, January 2017) is a horrific science fictional tale about violence and its origins, featuring such historical viewpoint characters as Jack the Ripper, Stalin, and Heinrich Himmler. He is also a past winner of the World Fantasy and British Fantasy Awards. A handbook on writing, Yours To Tell: Dialogues on the Art & Practice of Writing, written with his late wife Melanie, will appear early in 2017 from Apex Books. In the Fall of 2018 Colorado-based HEX Publications will bring out his young adult Halloween novel The Mask Shop of Doctor Blaack (note that Blaack is not a typo).

The Tem home on the web: www.m-s-tem.com. The Steve Rasnic Tem Amazon page: http://tinyurl.com/jy3favs

Read an excerpt from UBO by Steve Rasnic Tem, forthcoming from Solaris Books, January 2017

Amazon pre-order page: http://tinyurl.com/gm6u2vx

Chapter 4.

The insect voices at the back of his brain might have taken him anywhere. Often there was a time just before the dream was over and a new scenario began that he thought they may have taken him to some prehistoric place and left him there, some lost landscape of hard shell and claw and bodies torn and leaking. They’d sent him to where they wanted him, to where he needed to be. They’d left him with barbed, narrow legs in his thoughts, hard exoskeletons at the periphery of his vision.

Daniel came to again while staring up at the sky. The smell here was worse than Ubo, worse than anywhere he’d ever been. He could see blackened, crumbling brick buildings in his peripheral vision, moist and dripping, a thick red sky. And all he could smell was that stench of raw sewage. He wanted to look down and make sure he wasn’t standing in it, but the character he had entered was singularly focused on that sky and wouldn’t allow it.

Daniel was surrounded by a wall of noise, beating against him from all sides, and yet his character had somehow turned it off, refusing to hear it. It was as if his new persona had eaten him.

Daniel was surrounded by a wall of noise, beating against him from all sides, and yet his character had somehow turned it off, refusing to hear it. It was as if his new persona had eaten him.

A black plume of smoke thrust itself across the red sky, stalled, then began to dissipate into air already heavy with particles. This left some patches of sky looking oilier than others; he could see the small green and purple and blue rainbows that oil makes in a puddle.

Then the head snapped down and around and the sound came rushing back in: an incredible clatter, layer upon layer of thousands of rattling carts and buggies pouring down the kennetseeno streets, metal shod wheels on cobblestone, and their vibrating shells all sounding as if they were shaking themselves to pieces, punctuated by the more pleasing rhythm of the horses’ iron-clad hooves. Then there were the sellers, the street criers, their shouted words overlapping until he had no idea what they were saying, except the periodic exclamation of “Buy! Buy! Buy!” And then lording over them all the melodic notes of the bell tower at Christ Church, pealing out the hour.

Christ Church? And all this smoke and sewage, buggy rattling. London in the Victorian era, certainly. Early industrial London, incredibly filthy city. He never would have believed the amount of pollution that could be generated by coal, tons and tons of it burning all the time, if he hadn’t been seeing it himself.

Spitalfields, his character thought, as if in answer. And The Chapel. Whitechapel. And Daniel felt his own thoughts falling away into tatters as an old rage tore up out of the deep shadows and consumed him.

A ballad monger stood on the corner, his broad sheets tied around his hat, his head dropping back (slice, slice!) as he began to bellow,

“Now Mrs. Potts says she, I’d let the villain see,

If I had him here I’d sure to make him cough,

I’d chop off all his toes, then his ears and then his nose,

And I’d make him such a proper drop of broth,

His hat and coat I’d stew and flavor it with glue,

Blackbeetles, mottled soap, and boil the lot,

I’ve got a good sized funnel I’d stick it in his guzzle,

And make humbug eat it boiling hot…”

And all around him the folks was laughing and jostling, speaking of Jack the Ripper. Well, that weren’t his name, now was it? But he didn’t like the name his bastard of a pa give him, so Jack would do, all jolly the way they said it now, or all full of fear the way they said it at night. Happy Jack—though he’d never been happy as far as he membered–or Sad Jack or Rippin Jack it was all him. Never mind wot they said in the papers. He didn’t read them, just heard about them, and their lies, because he’d never writ any of them letters, or called hisself Jack. But Jack, Happy Jack would do.

Oh, he knew how to read and write well enough—one of his pa’s old customers was a proper gent, some kind of professor fell into drink and become a lushington. He stank of hair oil, his bloody whiskers all curled up in bacca-pipes. Before he died—a do down one night with a holywater sprinkler bashing his noggin–he taught Jack plenty, including things Happy Jack wouldn’t think about. But Jack never liked the way the read and the writ words felt in his head, all bumping around and hurtful like a tin cup full of stones. Each word like a new voice in his head, and him with too many in there already. The “mad multitudes,” to quote Milton, the way the professor always done.

But the words kept coming none the less, with all their temptations and colorful suggestions. There was that other bloke the professor was always quoting, now wasn’t there? Something Blake? “Sooner murder an infant in the cradle (a terrible thing!) than nurse unacted desire.”

Jack never set out to be no trassewno. He never wanted to hold a candle to the devil. He weren’t born evil, no matter wot the papers or the ballad criers said. Oh, he knew life. He’d done his share o’ area diving round the Chapel, some beak hunting (he dearly loved them chickens!), bug hunting, a bit of blag. But he weren’t a bludger at first. All that bloody business come after living too many years in Hell, hearing the church bells every day and thinking about wot they promised, and then getting none of it. The Chapel were a long ways from Heaven.

Then a film come over Jack’s lamps, like it done most days ahead of sunset, betwixt three and four. Soon enough you’d hardly see your hand in front of your face, even with the gas lamps on, with all the black bits in the air. But Jack got dark afore the rest. Jack got dark with the sun still blazin high. He could see all them other blokes walking about in the afternoon of their day when for him it was nigh midnight. Not like he favored the dark, or being alone and such. The dark left him with a sick feeling in his belly and salt on his tongue, with all the times he membered living there, no matter the time of day.

So he started moving, running in his big gallies into folk, knocking em down, not cause he was of a mind to hurt nobody but cause he wanted to run out of there, run out of London if he could. Folks shouted at him, cause they knew him, though they didn’t know him as Jack.

The ripper distracted, Daniel floated up through the swirl of madness, past the thoughts of bloody hole, filth and scum and a rotting taste going down as deep as the lungs, as if seeking a gulp of clean air. He’d never experienced such chaos in a character before, not even in a murdering thug like Jesse James or a monster like Caligula, both clearly reasoning people compared to this one.

He was playing a character and the character was part him and part what the roaches had been able to find out or recreate. But the experience of being inside a character was always different, and sometimes even varied widely over the span of a single visitation.

Sometimes, like this time with Jack the Ripper, you were swallowed completely, so there seemed no difference between Jack’s thoughts and your thoughts, and looking out Jack’s eyes was the same as looking out of your own, and you smelled the stench with Jack’s nose, and when Jack raged that was you raging as well.

These were the hardest characters to shake later, when you woke up back in the barracks. You’d feel the most guilt over what Jack had done, and you’d have flashbacks into the character at the most inopportune times, like when you were eating dinner, or thinking of the family you’d left behind, and you’d curl up into a ball on the floor, knowing that a hundred showers wouldn’t wash all that filth away.

Other times it felt as if you were riding within a bubble inside your character’s brain. You could hear everything, and feel everything, but that was still you inside the bubble, horrified by everything your character was doing, and yet you were forced to watch. Their rage was not your rage—in fact when they raged against their victims, it also felt as if they were raging against you.

But if you were lucky, the walls of that bubble might be thick enough that you didn’t hear everything your character said, or see everything your character did, and sometimes you could even close your eyes and pretend you were back home with your family, no matter how hard the roaches tried to yank you out of there.

An invasion of nausea rose out of the ripper then, draining any thought of an earlier- or later day London, or of a Daniel or Jesse James or Caligula or of any other lifetime. There was only this . . .

He was here and now, trapped here in Jack, Happy Jack. Once again a tide of salt water lapped at his throat as he emptied himself of Daniel, was drained of any memories of a time or a place other than this. Inside the dark part of his eyeballs he could see a roach head, black eye globes glistening, barbed legs sawing against his tender brain tissue. A skittering through his head as the roach thoughts clawed, digging for some kind of understanding of why Jack done what he done. Like Jack had any idea at all.

Whitechapel High Street. A man with a rough old face, his patchy white beard like some kind of infection, goaded a small drove of cattle down the street toward the slaughterhouses at Aldgate. Deerstalker cap, brown kecks and a cutaway coat even all that dunnage couldn’t hide the filthy white hair on the man’s face. Jack imagined that if he stripped off the coat he’d find more hair running the fullness of the man’s body, matted with cow shite and other filth.

Jack stared at the cuffs of the man’s trousers. They was so badly frayed he wondered if a dog had chewed them, or the man’s own cows when he slept with them. Mud speckled him from his cracked leather crabshells to his beard-eaten face. Jack could see the tiny balls of mud or maybe they was shite clinging to the ends of the man’s whiskers, as the horns of the lead animal snagged Jack’s coat. An explosion went off in Jack’s head, as much terror as anger. And suddenly he was God bringing the mayhem down on this transgressor.

Jack punched the man on the shoulder. “On yer way! Outta the street!” The old man raised his cane, looking startled, unable to speak. Jack punched him in the face. He felt the nose give way like it was made of eggshell. Blood spurted from one nostril, thickly painting the beard. Jack rocked back and forth on his feet, acting the bruiser, hitting at the old man, who was now trying to maneuver himself behind his cattle. Jack slapped out at his face, but a shoulder got in the way. The old man stumbled back against a cow, and Jack tried to pursue him around the lead animal, careful to avoid the horns. The cattle stirred restlessly, moaning deep in their throats.

“You!” Jack turned to see the copper splashing toward him through the stream of sewage in the lane. “Stop!”

Jack turned to the old man with a grin, nodded once at the blood spotting his coat and waist length beard, then hit him again, this time tagging a cheek. He could feel the crisp crack of bone beneath the mushy face afore the man went down, nobbled. The cattle bolted ahead of him as Jack ran, laughing. The brief beating had gotten his blood up, made his palms sweat, his lungs flutter. He’d have to get the tension out now; there was just no helping it. A fist fight or some quick work with a shiv, anything to raise his head a bit, keep the blood up. He laughed out loud. He howled, then bayed at a startled old lady in a black hood. His palms itched. His throat was so dry he knew he could down a full flagon on the run. He could smash gents’ heads and tear into ladies’ faces with his teeth. Spit em out and dance on the soft parts. Bloody, bloody kids and dollymops with their soft bits turned out. All their hanging down parts spotted with black soot and the sewage from the streets. Can’t be leaving your soft parts hanging. He’d found that out a long time ago. Asking for it if you did. The only way to have anything would be to raise the blood and spit and beat on it, break off the filth. Scratch it out. Then you’d be a giddy one, living higher than the steeple. You’d be a giddy bloody king, you’d be. Nobody gives it to you. You expect that and you’re lying in the street, letting the blood flow till it’s cold. The rich and the lovers and the famous gents all got their blood running hot. Jack’d found a way to get his blood hot, too. They had no idea. Helpless as cattle in the street.

Armored wings fluttering, barbed legs dancing in the shadows, antennae kiss to his lips . . .

Jack slowed to a stop after a couple of blocks. He picked up an old felt hat some swell had lost and ripped it with both hands, gnawing at the damp material. Felt like badger meat, or squirrel maybe, after it’s been left to soak. Tough but chewy. He bit his lip hard and sucked out a little bloody salt. No copper’d catch him, not that way, and not here. Who’d care anyway, in this sty?

It was a spiderweb of alleys and courts here. A shroud of dark shadow lay over everything, a blackish scum. Looked like shite, and Happy Jack liked to think it was shite. He imagined he smelled it all the time, even in his sleep. And throughout most of the area there was also a heavier layer greasy rags and trash ancient when Jack’s judy of a mother was born, all glued together with liquid sewage into a kind of caul that slipped into all the cellars and slopped up into the house if you wasn’t careful. A separate country it was, a different world, even with the East End but a short distance from Bishopgate and the Leather Market and the Bank of England.

Jack knew the secret, though. They wasn’t human beings. How could human beings live six or seven or even twenty to a room? Rooms and rooms full of them lost souls, all the rooms of Hell.

He stopped, bewildered, then began to cry to himself. He let the tears wash out the gray city, and for a moment even the stench was missing from his enormous head, his skull full of the mad multitudes. He’d kill them all, he would. He’d kill them all. They was children dying . . . they was dying everywhere.

“Yer borned dead . . .” his flummut daddy once told him. “They bring your bloody carcass into this wurld and they slap ye good ‘n silly so’s you’ll live and they do pretend pretty yer alive but you was borned dead . . .”

A scratching at his brain . . . their damned hard barbed legs. Wings across his eyes. Their enormous eyes always watching.

He membered that time he’d followed one of the ladybirds plying her trade on his street—she’d flashed her Miss Laycock at him and musta figured he’d pay her for the privilege–down down through a basement kitchen stinking of sin and the corruptions of the flesh, through a narrie hall moist and red, when she pulled him into her kes and turned her back, lifting her dress to show off her Nancy, pushing its plumpness against his Nebuchadneezar, and him about to do her in, he stepped off and messed around in his trousers looking for his shiv, when he seed that wee foot tucked under the edge of the bed, pulled on it and the dead tot slid out, its eyes closed and mouth open that wee angel singing his way into death, a brown stained bundle too small even to raise a stench. Jack looking down at it like it was a wee puppy drowned, and her turning round saying she had no knowledge of the thing. Leaving it to Happy Jack to dispose of.

Jack got out quick, forgetting her well-deserved murder.

They was mothers here in The Chapel, death mothers all, who’d turn their children into the streets at night because they let their rooms for whoring. Leave their own baby children out till past midnight, out there with the loafers and criminals to sleep with em in whatever staircase, doorway, dustbin, or loo they could find. But at least that was more money for the children than being a sackmaker for a farthing each or tuppence farthing a gross matchbox making.

Jack swung his foot at two shy-of-ten year coupling in the pathway. Connected right solid, but he felt no pleasure in it. He started thinking of the Eddowes woman, and what everybody had said. Ripped her up like a “pig in the market,” they’d all said. “Her entrails flung in a heap about her neck,” they’d said, their eyes gleaming.

Maybe he done it that way. He couldn’t member it rightly. But if they got them particulars from the papers they got em wrong.

Jack made his way toward his doss on Flower and Dean Street. His pa run that one, and even though he was the very devil Jack knew he was lucky to have the free deb and not have to pay the 4p, which was more than he had most days. All he had to do was not speak to the man or let on that the warden was his pa. But everybody knew anyway, seeing as how he didn’t have to show no tin ticket to get his bed.

They was some Irishmen round the front door smoking their short pipes, a couple old women with walnuts in their hands, a fellow in tar-smeared trousers tearing up a piece of gray chicken with his dirty fingers, stuffing it in his mouth, watching against them what would steal it. Two children dressed in a mismatch of rags huddled against the wall close by. They’d been there the day before–Jack figured they was dead or sleeping but he didn’t want to be the one to check. He went down the steps into the area. His pa was there in his little booth. They locked eyes but neither said nothing. Jack walked into the kitchen and the big fellow with the burnt face and no name tossed him a bit of the herring he’d been toasting. The stench of it filled the downstairs. That was the way his pa sometimes give him some food—always from somebody else’s hand. A fellow might think the old man was bang up to the elephant, except that very same day he might betray Jack, fill his bed with some stranger so that Jack had to go somewheres else or fight for his bed.

Two old fellows was sitting at the table spreading the broads. Jack didn’t know the stakes, but there was a couple of gen on the table. When they seed Jack one of them covered the shillings with a rough hand that looked mashed and crooked. Jack didn’t care—he never stole in the doss house.

There was a bunch of others lying around on the benches, coopered. One skinny bloke he’d seen afore, and he couldn’t figure how the fellow was still breathing air. He had a head like a lamb been sheered, starved, his wrinkles crisp as folded paper. He breathed like he been punched with every gulp.

Jack climbed the stairs to the beds—another way he was treated special. Every other soul had to wait. The broken windows patched with rags and paper. Hardly no air, even through the ones they could open, and everything stinking from no proper washing. He found the old bed where they said his ma used to sleep, and his, the one he still had. Seven foot long but not even two across, a four foot tall wood partition on both sides. Like a coffin, though he never understood why a body needed such a thing. When you ain’t gonna wake up who cares where?

He was beginning to feel a might glocky and went back downstairs. He got that way sometimes, not wanting to sleep in the room with all them other people. He waited until nobody was in the downstairs hall, crouched down, and pulled aside a couple of boards under the stairs, crawled in like a snakeman on a burglary. The vein he was in was dark and smelled like the world was dying, same as it always had.

In the first stretch he didn’t have a lamp, but he didn’t need one. He’d known the way almost since he was born, after his pa stuck his ma in this hole, her being pregnant and him not wanting nobody to know.

So she’d laid in here until she died, him inside her. Pa said he found Jack like he’d just crawled out of her filth hole, like the rutting and the birthing and the dying was all the same to her, and here Jack was still hanging by the cord. And it might ha’ been that way, but there was no way for him to know now for positive.

Over the years Jack had dug it out further. It went down in under the foundations between the buildings, widening out as it went until you couldn’t stand but you could almost. Finally he got there where he kept a lamp and some food, a bed of straw and rags, a few secret treasures, all to hisself. Most would think it a terrible place to be, some kind of way station along the road to Hell, but he still felt safer than upstairs with all them others watching him dream. It was a quiet place where he could bury hisself in sleep.

Did she scream in pain when she brought him out of one dark and into another? Or was she screaming in pleasure, or maybe there weren’t no difference no more? Did she know she’d even had him? Sometimes Jack could conjure up her voice and he’d lie there for hours listening to her speak. Born from a dead mother, that was Jack’s story. It was a short one, but it said all that was needed. And it always made him grin.

Oh, Jack had always been a grinner. His pa reckoned it were a tic because of the way Jack was born. Growing up he tried to control the grin, but the flesh above his upper lip bunched and fought him all the way. It pinched his nostrils, making him look like he was always smelling a bad smell. And the more he got excited, the more he felt about anything, the more he grinned. Happy Jack was a grinning fool.

That’s why he grew that dark moustache. The grin was always under there, but now nobody else could see it.

He felt the roaches’ legs at his lips, stiff wings brushing his thighs. He began to cry as the roach mounted him, carrying him deeper into the darkness, but at least he could sleep, come at the cost of one of them awful dreams.

#

“Jack? You asleep, Jack?”

He opened his eyes. “Ain’t my name. Least not one anybody else can use.”

The other eyes stared back. “Sorry. Penny for a suck?”

Jack struck out but there was nothing there. Then he saw the lad, half there and half not. But the boy was just a child, doing what others taught him. He needed to be patient with the lad.

Jack had no idea what time it was outside. Down in here it was always night time, dirt time, dead time. But he was too awake to stay dead, so he climbed out of his hole and went back out into The Chapel.

This was when they come out. The haybags with that particular look about them, the dollymops and the judys and the night flowers and the three-penny-uprights what had no money for a doss, or the ones what had given up, now waiting for Fate to come and decide. The ones so plain about it the death waiting in their soft parts. The death mothers. The teeth mothers. Dry wings raking, scraping the back of his brain. Oh mother of God forgive me as I . . . he whispered softly, as to a dream.

“Come on, Jack. Time to do your business.” The lad walked ahead of him, leading him down the path. They’d done it all his life, leading him down one path or the other. But Jack followed, the London Particular so thick he couldn’t find his hand afore his face. “Come on, Jack,” the boy kept repeating. Jack followed the voice.

Hands kept coming at him out of the soup, like the walls and the dark itself had growed em. It was all he could do to keep hisself from slicing them hands off, but he wouldn’t be distracted—he had to follow the lad. The lanes was full of lurkers, mumpers, and gegors with them hands out, griddling him for some coin or some food.

He’d battered a few at first . . . no knives then; he hadn’t yet seen his calling. They’d bend over and spread their dresses for him in the alleys, and then he’d push their faces into the wall and beat ’em there. He took no pleasure in it. That was the point. Not a thing he done was about pleasures.

He’d started a long time ago, just a lad hisself, tearing up whatever he could get his hands on, acting the master of mayhem. His pa kept him locked up most days, said he couldn’t trust him round the belongings. Then there was Jack’s little parties in private, down in his secret place or in some quiet lane with the mice and the birds, all done serious like, like he was a surgeon, or a priest in a church. Taking things apart weren’t much different from putting them together in the first place, now was it? And God done both, two sides of the same hand. God the Father and God the Mayhem. But them little parties just didn’t raise the blood no more.

Happy Jack thought he could see blazing white pantalettes and bloomers hanging in the dark, with just ever so much soiling. He thought of dead bodies casting off their clothes underground, like snakes shedding skin, all them unmentionables leeching to the top . . . barbed black legs and antennae raking at him passionately . . . Happy Jack could not escape from Hell. He could not love enough. Where was the lad now? He stumbled into one hidden court after another looking for him. No kingdom of peace for Happy Jack. No smiling family. No loving wife. No child to carry on his face. Just the dead mothers, always in his way, stopping him. So he’d turned around and gone a different way.

“Don’t be a mewler, Jack,” the lad said out of the soup just ahead. “You’ll need some dash-fire in your belly if you’re to survive The Chapel.”

Jack went off his onion then, couldn’t believe the boy’s bloody cheek to speak that way. To Jack of all people, who’d had to endure the fires of Hell afore he got to that babe’s age. He commenced a run into the fog, bellowing like a bull and mad as hops. Course he couldn’t find him, the boy having enough brains to run off by then.

He run into the usual collection of beggars and whores instead, his boots mashing the softer bits of them unfortunates, and the times being what they was he heard more than the usual portion of screaming, what with the whole populace down with the vapors over this Jack the Ripper affair, and just for a spell he forgot it was him they was referring to. He weren’t no big toad—he was just doing what he had to do. They all had their own stories about what he done.

Had he really eaten the kidney of that Eddowes woman? He didn’t think so. He was disgusted by the very notion. They was saying he cut open the bodies and made off with his little souvenirs, and maybe sometimes he did. Sometimes he’d find things he didn’t understand when he’d opened them up, things what made him curious. So maybe he’d put em in a pouch and take em home with him. He’d usually forget about em afterwards, or lose em. He thought probably the rats what was always visiting him made off with them souvenirs.

Sometimes he’d smell the bits, putting em against his face to see how soft they was. They smelled the way he spected women to smell. Sometimes he’d look for any dead babies they might be hiding. Something about sorting through all the pieces made him feel like he wasn’t all by hisself. He’d loved nary a woman alive.

He might ha’ eaten that kidney. Sometimes he liked the taste of piss. But probably not.

Daniel swam up, gagging. Jack stumbled on his way through Hell. Mandibles tore open the back of his head. Mandibles and antennae and sharp sharp barbed legs dry hardened wings sharp as a razor for slicing off sections of the brain. In a frenzy they bore him down into the filthy street, their quick jabs growing fainter as they injected him, the memories and the stories and the speculations feeding back into his head, the sap rising up his spinal column easing him, erasing him, until Daniel was swallowed up in his own bile and he was Happy Jack once again.

Happy Jack. From Hell.

So excited he was that he quite bit through his bottom lip on the right side, and spent several minutes sucking the blood, almost desperate to keep the salt and iron taste flowing, priming his taste buds. He had never known a woman completely. They couldn’t all be nasty whores. He had never known pleasure. He had never known a life outside his own skin.

The women in the street taunted him, dared him, their invitations framed in lace and painted lips. It was the paint that infuriated him most, making it obvious they knew all too well what they was doing, what they set out to do. Their special crime was that they made it all too obvious what it was all about, all that tedious waiting for your final hour and the death neverending. They drifted in and out of the dark alleys, the shadow holes, as in a fever dream. Sluts and pus wells all.

Confronting the harlots had become gradually more difficult. Their dirtiness fascinated and repelled him how unbelievably, beautifully dirty they was. The ground made into flesh. Like they had to dig themselves up every night for their lust time. Each time it was more of a chore to get the same ecstatic effect. They seemed far more in control of the event than he, drawing him further and further into their enticements. The death mothers weren’t likely to release him anytime soon.

He’d been watching Mary Kelly for months. Some¬thing special about this one, his feelings for her. Most of the judys was plain, washed out things. Not her—she still had a freshness and good looks on her. He’d spent many a night sitting across from her lodgings at Number 26 Dorset Street. Or following her in the shadows as she left The Queen’s Head pub. The lodging house keeper, John M’Carthy, knew his pa, and had told Jack quite a bit about the woman, thinking Jack was less than he was, and the man liked to hear hisself talk. Her room was number 13 and had its own entrance onto the narrow street.

It was the fact that he found her so attractive that threw Jack off; he couldn’t make himself go in and just dispatch her. Not like that. And that drove him mad. For in all other ways she was like every other whore what brought a poor whelp into this world, and everything what was wrong about The Chapel. She was dead, she was walking around meat; she just didn’t know it.

Most of the houses around her was full of whores, most of the windows boarded, and opposite Miller’s Court was that doss with three hundred beds, filled every night. Her pretty face kept her busy—Jack counted several customers a night. She was always working Aldgate and Leman Street. She had a broken window, stuffed with a rag, and Jack had seen her reach through, push back the ragged muslin, and unlatch the door several times the past few days. Looked like she’d lost the key.

Maybe he best be careful; never afore had he hung around so long. But no one knew what he looked like. He’d heard he was pale, then he was swarthy, slight moustache, heavy or none, long dark coat, red coat, hunter’s coat, light waistcoat with a thick gold chain, trousers and garters, red handkerchief, a foreign look, a twinkle in the eye—every man Jack of em seed something different, suspected a different neighbor or renter, father or doctor or reverend or husband to be. Anyone could ha’ done them crimes—that’s what drove em all crazy.

Jack had visited Mary Kelly’s window the past few nights for a peek, when he knew she was gone. A bed, a chair, two tables. That was all. Some lace hung up by the window, a touch of the girl still in her. He caught himself wondering what it might be like to be living there with her. It made him angry with hisself; he might as well hope to be an angel up in Heaven.

He thought she might be pregnant. He had a special sense about such things. He could smell it on her.

Here the babies was all dying and the slut was bringing another dead child into the world. Jack could see it dangling blue faced from its cord, wrapped around her waist like some prized belt. He reminded himself–this harlot was like all the rest.

In the darkness of the filthy street a child was softly

crying. Jack looked around but could not see the babe. He wondered if it was drowning, half dead under a pile of filthy rags, left abandoned in some darkened doorway, or what. The young ones had no chance. Their dead mothers was raising a nation of children with no one, a nation of staggerers wandering them alleys alone. They had to be stopped.

Teeth grinning a blade, scummy eyes shining under the gaslight. The lad had returned, standing in the darkness behind him. Happy Jack whirled about and reached for him. The boy was starved, and the largeness of his hunger stopped Jack. The boy’s eyes burned, pushing him.

“Do it,” the boy said.

“No, not tonight.”

“Don’t be a mewler, Jack. You’re going to feel good with this one. You’re going to feel quite a bit more than yourself.”

Mary Kelly wandered back from the public houses on Commercial Street about 11:45 p.m. She couldn’t manage more than a drunken wobble. She had with her a short, fatty pig of a man, ragged sleeves and a billycock hat, thick moustache, still carrying his beer from the inn.

“Goodnight, Mary,” someone said out of the darkness. A woman’s voice, but it could ha’ come from anywhere. Jack’s own head maybe? But he couldn’t be bothered thinking on it, so busy he was watching his love and his hate dancing around with the filthy bulldog of a man.

“Goodnight,” Mary called out. “I’m going to have a song.” She then began to sing “Only a violet I plucked from my Mother’s Grave when a Boy.” It was ugly and off-tune but it was still like a needle going into Jack’s heart.

Happy Jack watched her reach through the broken window and unlatch the door, then drag the fat sack of meat in with her. A short time later the pig stumbled out and went his way.

Jack turned toward the shadows. Tiny teeth gleamed. And somewhere a child was crying. At that moment he doubted Mary Kelly would resist; she wouldn’t have it in her. For she was already dead, now wasn’t she? And Happy Jack had come. Death would be too beautiful for her to refuse.

The paving stones beneath his feet was slick with human filth. He felt hisself stumble, and a pale arm come out of the filth and righted him. As far as he could see: dead bodies lolling in the alleys and doorways, their pale flesh beautiful in the moonlight. He and the lad stepped over them easily, the soft body parts rubbing against their progress. He and the lad. Happy Jack and the babe. Duly ordained and intent on their mission.

Happy Jack. Happy Jack. He walked to the broken window and reached through the space into the darkness of Mary Kelly’s room. He unlatched the door, stepped there, and was through.

She wore a thin chemise to bed. He couldn’t see her face in the darkness. He suddenly thought he might swoon with the power he had over her he didn’t know how he could bear it. Once again the world was his and everyone had to know this. She didn’t know she was already dead. Happy Jack had a duty to tell her. He had a way to excite her.

With each stroke he felt he was erecting something higher, building a monument in his heart with each thrust and twist as the blood thickened and raced, ran up his veins and exploded out to mend the world.

Once, maybe twice, maybe even a third time she said it. “Oh! Murder!” But very softly, as if she really didn’t care. Jack doubted anyone else could hear her.

The first thing he knew of it there was two chunks of flesh lying on the table in front of the bed. How had it happened? Where had they come from? Then he looked back at his love in her white jawbone, white cheekbone, white-tooth grin. Smiling at his love for her. Wanting to reach down inside her and seize that love, bring it out for all to see, embrace her in a way she had never been embraced before, as he had never, ever been embraced. The throat had been cut clear across with a knife, nearly severing the head . . . but letting loose her grin. Both meaty breasts sliced off the trunk, and he started to go into the belly.

And the boy was asking him for the knife.

Jack stared at the boy with his grin, puzzled, thinking how wrong it’d be. Then handed him the knife.

The boy was all grin, thrilled with participation, as he began the work: hacking and slashing until the nose was all gone, and Happy Jack thinking Mary was lucky she didn’t have to smell The Chapel no more, didn’t have to smell her own dying. The left arm hung, like the head, by a flap of skin only.

Mary Kelly’s leg was suddenly grinning at him, speaking with harsh white and red sounds, and Jack seed the knife digging a trench to her bone. Happy Jack moved closer as the belly was slashed across and down, reaching in desperately to find the babe drowning in his mother’s filth, digging frantically, sure the lad would kill the new baby as well.

He had to pause once he was inside her, feeling the soft, warm wetness of her. Soothing as a baby’s touch, as old silk underwear falling apart in a trunk, as an old felt hat caught between the fingers. Again he bit into his lip and brought up some salt taste for comfort. He reached for the baby, for Mary Kelly’s love, determined to hold it, keep it, take it back with him to keep in his secret place under the ground.

He could not find the child alive in all that bloody flesh, even though he heard again and again its soft cries for help. He pulled away from the corpse mother, suddenly afraid of the boy with his knife. Jack looked down at the flesh in his hands, Mary Kelly’s liver, and placed it ever so gently on the bed between her feet, as if it was the babe. The boy looked back over his shoulder at Jack, grinning foolishly. And for some reason Jack found himself thinking of Christmas, and how a boy belonged with his toys and not in a Hell like this, and Jack giggled crazily, and reached in, and deep inside him Daniel managed to close his eyes, refusing to look.

When Daniel opened them again Happy Jack was staring into Mary Kelly’s face. Only the eyes were human. He’d ha’ blotted out the eyes too, their stubborn insistence on life turning his insides into a tortured twist, but he didn’t dare step past the grinning boy. He stepped back as the boy held the bloody knife out to him.

And then he had the knife in his hands, Mary Kelly’s eyes was on him, and the boy had again disappeared. Happy Jack sobbed as the barbed legs and mandibles raked away at the back of his skull in almost frantic rhythm. Something was breaking away here.

“My name . . . ” he cried and fell to his knees, sobbing, unable to complete the sentence or look at the bed.

Instead he gazed at the window. At dark mandibles and barbed lobes rising into two shadow faces framed by large, multi faceted eyes.