68 Years of Halloween by Steve Rasnic Tem

From last year’s Halloween Haunts, here is today’s Best Of….

I believe I was seven years old the first time I went trick-or-treating. Before that I wasn’t much aware of the holiday, and I certainly didn’t connect it with anything scary. I remember kids coming to the door in costume and getting candy—not too many because we lived in a very small Appalachian town. I was in my PJs, peeking out of the bedroom I shared with my two younger brothers. But that’s what I did when anyone came to the door—I was a painfully shy kid, and outside school and church I hid from people.

But the summer I was seven my mother bought my brothers and me matching Davy Crockett outfits. I was proud of the fake leather and fringe, but especially of the coonskin cap, just like the one Davy wore on TV. So that’s what we wore our first Halloween. No masks–why would I want to hide my identity? I wanted people to know I owned a coonskin cap.

That first Halloween my mother took us to two houses: our neighbors on either side. I don’t remember feeling cheated, though. We had enough candy, and it was dark outside, and I believed my mother when she said the world was a dangerous place.

That was my mother’s constant theme—how the world was this dangerous place that killed careless kids. And as Mom always told us, “when you’re dead you’re dead forever.” Not that I really understood what that meant. Does any child?

To reinforce her point my mother would tell us stories about little kids who were run over by cars while out trick-or-treating. “Smashed flatter than a pancake,” is the way she put it. Apparently they hadn’t looked both ways before crossing, or their masks had obscured their vision, or they’d run away from their parents’ supervision. But my mother’s fears about cars and children extended beyond Halloween. Once she showed us a large photograph from either Look or Life magazine. It was a woman on her knees in the street, her face split apart by grief. A few feet away there was a soiled sock, or maybe an empty shoe (sixty-year-old memories being prone to elaboration). According to the caption her child had just been struck and killed by a car. I had never seen such a shattered expression—it was a photo I would never forget. My mother was frightened of a wide range of things, but death by automobile was a common theme. My brothers and I always rode in the back seat, and if it started to rain or snow she would have us lie on the floor and hang on to each other. This infuriated our father (the driver unless he was too drunk). My brothers and I giggled through the experience, but I just always assumed my death, whenever it happened, would be via automobile.

After that first time trick-or-treating I looked forward to Halloween each year, planning my costume weeks ahead of time. Dreaming up elaborate costumes and drawing them to show my mother was my first creative outlet. Unfortunately I hadn’t the craft skills to bring these creations to life, and my mother’s sewing talents were minimal. My “mummy” consisted of strips cut out of an old sheet and sewn in overlapping bands to a T-shirt and some white jeans. More strips were wrapped tightly around my head and pinned to make a mask. This mask was torture to wear and after a few houses I tore it off in frustration. The rest of the costume unraveled steadily; I left a trail of strips all over the neighborhood as I ripped off pieces that had become a tripping hazard.

I tried for years to make a robot costume. My first attempts involved creating assemblages of pots and pans strung together with pieces of coat hanger wire. A conical colander seemed the ideal head piece. I banged myself up pretty good testing it out around the house until my mother made me take it all off. Late versions involved cardboard boxes and tubes and plenty of aluminum foil and glued on old radio parts. None of these models lasted more than half an hour in actual use.

It didn’t seem to matter much. The responses I got at people’s doors were usually the same. There was an old fellow who bent down and said “ooh, so scary!” to every single child. I remember the year he didn’t show up, leaving his porch dark and uninviting. I found out later he’d died a few weeks before. And there was the woman who always came out and apologized to each of us because she couldn’t afford any candy that year, but maybe next. I was impressed, and wondered why she put herself through the embarrassment, and also, why did we return every year for that same speech?

Easier, more practical costumes came about around the time I decided I was a “bad” kid. Certainly most people didn’t see me as a bad kid. I was polite and good-natured and I behaved well at school. But I knew I had wells of rage and resentment good kids weren’t supposed to have. I hated my father—our relationship was one of violence, abuse, and humiliation. These bad feelings would linger until my mid-thirties when I finally recognized him as just another seriously flawed human being—and I forgave him for everything he had done to me. But in my childhood imagination he’d always been a monster (the supernatural bear in my first novel Excavation).

In fact one early Halloween I tried to recreate that monster in costume. I had one of those giant stuffed bears from the county fair which I gutted and then tried to fashion into some sort of chest-and-head mask. My plan was to use lipstick to draw fangs on the muzzle and generously drip some my mother’s red nail polish over the fur. But although the stuffed bear’s head had looked plenty big enough it was still much too small to get over my head (which was wide and perfectly flat in the back). And I could already tell it would have been unbearably scratchy. I went as a bearded hobo instead and told my parents the dog had torn my bear apart.

The one area where my “badness” was on full display was in my treatment of my two brothers (who weren’t subjected to the same physical abuse I was). I bullied them terribly, I’m ashamed to say, by means of dangerous practical jokes involving darts and other sharp objects, electricity and bare wiring, fire and fireworks—jokes which I could pull back just in time but which still might have caused my brothers serious harm. I fancied myself some sort of mad scientist, and I played the part well.

I had a religious upbringing, and I was sure I was going to Hell because of both my obvious and secret sins. I listened carefully to the sermons on Hell I was exposed to, and I couldn’t figure out how to avoid it. In fact, according to some of those preachers Hell was my final destination from the day I was born. Staring at a dark cloudy sky late in the afternoon I sometimes imagined I saw God looking down on me, ready to send a tornado down to carry me off to my judgement.

So for Halloween I started dressing in rough clothes—a variation on my old hobo theme—with a hood of some sort (my “executioner’s hood”) to hide my identity. That was the key part of it. I usually went trick-or-treating by myself, disguising my voice as best I could and refusing to answer any questions as to my identity or anything else. I didn’t want to leave any clues that would connect the “me” everyone knew to the bad kid/secret self I was trying to dress up as—the one that was going to Hell. Up until and including my last time trick-or-treating (the subject of my earlier Halloween essay “A Condemned Man”) these were the types of costumes I wore. I knew next to nothing of the history of Halloween, but I had a notion that dark duality might be more in keeping with its true spirit.

For a long time after high school and through my college years Halloween was not something I thought about, except in a generally negative way, which may be somewhat strange for a horror writer to say—it’s supposed to be our favorite holiday. But I was an intensely serious young man and Halloween, of all the holidays, seemed the most frivolous. In those days I knew I wanted to be a writer of some kind, but I hadn’t yet come up with an approach that suited me. I had written a few stories and they were pretty dark, and I knew exploring the dark side of humanity was something I was interested in, in part as a way to understand my own dark vision of myself. I was also interested in secret histories, suppressed knowledge, the parts of life which most people, I felt, hypocritically ignored. In college I had discovered the dark fabulism in writers such as Borges, Calvino, Kafka, Barthelme, and Edson. I was also seriously impressed by such grim 60s movies as The Birds, The Haunting, Psycho, Repulsion, and Night of the Living Dead. I recognized this as a creative direction I wanted to follow, if I could only figure out my path through it.

But I did not associate this content necessarily with Halloween or with horror in general. There is a saying among religious folk concerning the Christmas holiday: “Remember the reason for the season.” But that’s not something you ever hear concerning Halloween. If anything, people want to ignore the origins, the rationale behind Halloween. Certainly those origins are something we’re hesitant to discuss with our children. To tell your child this is the night when the boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead become blurred, when the ghosts of the dead are said to return to earth, is not a conversation most of us know how to start.

At that point in my life Halloween appeared to be more about a denial of death and darkness, defusing its implications so little kids could play dress-up and score free candy and older kids would have the opportunity to party and raise a little hell. One of the Halloween legends about VPI was how early students, most coming from Virginia’s farms, managed to get cows and other livestock into dormitory rooms and up on classroom building rooftops. This, I thought, was what Halloween was really about: an excuse for mayhem.

Most of the horror movies I’d seen seemed to suffer from this same “Halloween pretense.” The scares seemed arbitrary, or at least nothing the average person would likely encounter. As in the Grand Guignol, the audience seemed to have entered into a tacit agreement with the filmmakers that they would scream at situations portrayed on the screen as long as they weren’t affected in some deep and personal way.

That may seem harsh, but that’s the way I felt at the time. Halloween, and the horror genre in general, seemed a disappointment—instead of an engagement, it seemed more a series of entertainments designed to avoid direct contact with what was actually disturbing and terrifying. I wanted to explore darkness in my fiction, but strangely enough horror didn’t seem to be the best place for it.

Obviously my attitude changed. The problem was I had been distracted by the popular iconography of horror. The classic monsters, the orange pumpkins and the skeletons and the bats, even the color black itself had become so identified with horror they obscured what was still true and vital about the genre. I simply hadn’t read enough.

I first encountered Ramsey Campbell’s work in a bookshop in Ft. Collins, Colorado where I was working toward a Master’s in Creative Writing at CSU. I had never heard the name, but just dipping into the pages at random I was blown away. Somehow he had mastered the ability to marshal the details on each page in a way that led the reader from the specifics of the everyday world into the interior landscape of an anxious and paranoid mind. And this didn’t happen just once, but throughout the book. I was soon reading everything by Campbell I could get my hands on, and reading Campbell led me to other contemporary horror writers such as Dennis Etchison, Robert Aickman, and Charles L. Grant. I also rediscovered the ghost story through Campbell, including M.R. James and the entire Jamesian school (some of which I had read in high school, but I had never connected ghostly fiction with horror fiction before). I knew immediately this was the kind of fiction I wanted to write because the stories played with imaginative, impossible realities while managing at the same time to reveal essential truths about the human condition.

It took much longer for me to rekindle my enthusiasm for Halloween, and I can thank my children for that. Shortly after I married my late wife Melanie we adopted five children over a period of about ten years. These were young children who came out of abusive homes, who had been through both failed foster care and failed adoptive placements. They’d been through more real trauma than I like to think about. And yet they all loved Halloween, and loved scary stories.

My oldest daughter wanted to be a princess every year, and I have to say she made a beautiful one. She also developed a passion for zombie stories, which still holds true now she’s in her forties. My son Anthony, who passed away at nine, insisted on being a blond vampire each Halloween. My youngest son was a soldier most years, and still loves masks—the more hideous the better. When he pulls one of those masks over his three-year-old daughter’s head it gives even me the creeps.

When we first adopted these children I was very careful with anything scary. No scary movies, no scary teasing. After all, hadn’t they been through enough? But much to my surprise, they had a natural craving for this form of entertainment. More importantly, they wanted and needed to explore the differences between real danger and pretend danger within the support of a safe and loving environment. They wanted to know how to make nontoxic choices. Through story and through costume they wanted to defuse the very real darkness which had haunted their early lives. This was the kind of darkness I believed I understood.

Halloween became an important time in our family, and eventually, my favorite holiday. We spent hours carving pumpkins and decorating, and when we were in town Melanie and I dressed up to hand out treats. She insisted we have healthy choices available for the smaller kids, and finding something nice to say about every costume became my assigned task (although the little kids were usually happiest with an “ooh, so scary!”—sometimes you just can’t beat the classics).

Not that these Halloweens were always trouble-free. The year our son Anthony died we just didn’t think we could handle our first Halloween without him. It was one of the reasons we went to England that year for the first overseas World Fantasy Convention. But your dreams, like some stories, persistently foil your attempts to avoid. Several nights while we were in London I dreamed I was at our door giving out Halloween candy when a small child dressed as a blond vampire came up on the porch, held out his grocery sack, and exclaimed “Trick or Treat!” in the unscariest voice imaginable. I felt devastated trying to decide whether I should tell him he couldn’t go Trick or Treating anymore.

Then there was Melanie’s last Halloween. Her cancer had come back and she was too weak to stand for very long. So we both sat on chairs by the front door so she could see the kids coming up on the porch in their costumes. We were disappointed because there seemed to be so few, but that’s been a trend the last few years. I’m told parents instead now take their younger kids to school and church events where the trick-or-treating is controlled and safe. Although the danger of tampered treats has basically been disproved, parents don’t want to take chances. I sympathize. Although I know better, I’m still my mother’s son.

Last year and the year before I had even fewer trick-or-treaters, maybe a dozen tops. I had lots of candy left over—some I begged my grown up kids to take, some I threw away. I don’t dare buy my favorite Candy Corn anymore (Did you know its original name was “Chicken Feed”?) at Halloween because I’m Type-2 diabetic and I would quickly eat it all and that would be an embarrassing way to die.

This year will be my 68thHalloween, and I’ll be waiting by the front door again. Given the previous years’ turnouts maybe I’ll have a book to read. And I’ll buy too much candy again because the possibility of running out and disappointing a child at Halloween is unacceptable.

If you drop by I’ll be that old guy, bent over, saying “ooh, so scary!” to each and every one of you.

#

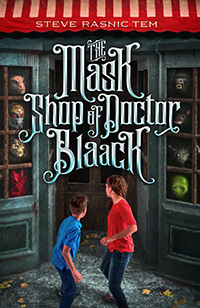

BIO: Steve Rasnic Tem is a past winner of the Bram Stoker, World Fantasy, and British Fantasy Awards. His novels include the Stoker-winning Blood Kin, UBO, Deadfall Hotel, The Book of Days, and with his late wife Melanie, Daughters and The Man on the Ceiling. A writing handbook, Yours To Tell: Dialogues on the Art & Practice of Writing, also written with Melanie, appeared in 2017 from Apex. His young adult Halloween novel The Mask Shop of Doctor Blaack will appear October 9 from HEX publishers. A YA collection Everything is Fine Now is forthcoming from Omnium Gatherum. He has published over 430 short stories. The best of these are in Figures Unseen: Selected Stories, from Valancourt Books. Visit Steve’s home on the web at www.stevetem.com

#

I’ve put everything I know about children’s experiences with Halloween and how they deal with darkness into my new middle-grade novel The Mask Shop of Doctor Blaack. You can order it from: http://www.hexpublishers.com/publications_the-mask-shop-of-doctor-blaack.html

For your entertainment, here is Chapter 5.

The Mask Shop of Doctor Blaack

Chapter 5.

Masks of mystery and masks of fun. Masks so silly you couldn’t look at them without laughing. And masks so sad they almost made you cry. And then there were those masks so terrible, so horrible, it made you wonder how people could sell things like that, how they could stand to have those awful things in their store. Surely the people selling those masks must have had the worst nightmares of all!

#

Now there was Laura, looking up at one of those horrifying masks, except it wasn’t a mask at all but the actual face of a human being, and she kept thinking that every time he looked into the mirror he must have made himself shudder.

“Are—are you the, the–” She couldn’t think of what to say. Her brain seemed to have stopped working. “–the shopkeeper?”

“Well, a-a-actually I prefer other terms. I suppose you mi-i-ight call me a kind of prosopologist, one who studies the human face. Except I study the faces of all kinds of creatures, including the faces of things which are not even creatures—furniture a-a-and machines and rock faces and the like. Everything has a face, I believe, although one is not always easily recognizable. But even more specifically, my interest lies in occurrences in which someone tries on the face of another, in other words, masks.”

Laura had no idea what he was talking about. But she thought it would be impolite to say so. She couldn’t tell how tall he was because he was bowing over her, his long thin legs bent awkwardly, the way a lot of adults made themselves smaller when talking to little kids. But she wasn’t a little kid—she was actually a little taller than average for her age, so she figured he must be unusually tall, taller than most any adult she’d ever met in person. He was soskinny, and maybe a littletoobendable. The way he moved his shoulders she thought maybe he had fewer bones than ordinary people. His head was long and narrow, and he had big teeth, just like a goat she saw once at a petting zoo.

She did what she often did when she was nervous, or confused. She apologized. “I’m sorry,” she said.

“Oh, he-a-avens! No need.” His throat bobbed and squirmed, and Laura wondered if maybe he had a kitten trapped inside. Or a rat. Yuck!

“This place is just so crowded, but I guess you know that already.”

“I prefer the term well-stocked,” he said, smiling with his thin lips while his eyes looked cold and hard.

“Oh, it is,” she said. “You must have everything here. But I have to go find my brother. He shouldn’t he left alone.”

“He’ll be fine, fine. Where could he go? I don’t have everything, I’m afraid. No one has everything—most of us learn tha-a-at, eventually. Although I ca-a-an’t imagine what sort of mask I might nothave. But certainly enough to satisfy your particular, little girl needs. Something for Halloween, or perha-a-aps something for everyday?”

She heard him call her a little girl, but she was too scared of him to let her anger show. “Every day?” she asked. “Who would want to wear a mask every day? That’s silly.” Then she realized she’d been rude. “I’m s-s-sorry,” she said again, stammering, thinking it probably sounded like she was making fun of his obvious speech problem.

“That’s quite all ri-ight, my dear,” Doctor Blaack said. “Sometimes putting on a mask permits us to forget our manners, and speak whatever it is we truly feel.”

“But I’m not wearing a mask,” she replied.

“You were angry, but you di-i-dn’t want to seem so. So you put on a mask, of sorts.”

“I didn’t mean to, but I guess I wanted to.”

“I’m not sure intention or ‘want’ applies, actually. Most of us simply can’t help ourselves.Most of us can’t go out the door without making sure our very special mask is in place. You know what I mean, don’t you little girl?”

“I’m not a little girl,” she said, trying not to sound angry. “I’m a teenager,” she said, although she didn’t always feel like a teenager. “And no, I don’t know what you mean.”

Doctor Blaack chuckled, then he said, “Have you ever gone to school, feeling quite sad, perhaps, or even moderately sad, but instead of frowning, or looking sad, you wore the biggest smile you could make?”

Laura thought about it, but only for a moment, because the answer was obvious. “Well, yes. More than once I guess.”

“And why did you do that, make a smile like that, when you didn’t feel like smiling at all?”

“I guess I didn’t want people to know I was sad.”

“And why not?”

“Oh, I don’t know. If they were polite, they’d ask me questions about why I looked sad, and when I’m sad, I don’t always want to answer a lot of questions. I want to be left alone. And if they weren’t polite, if they were the kind of person who teased people when they looked sad, well, obviously I wouldn’t want to give them the chance to do that to me.”

“Verrry good, my dear. So your smile, it was a mask. It just wasn’t a mask you put on. It was a mask you made with your face!”

“Well, when you put it that way, I guess that’s true.”

“Of course it is. And would it surprise you to hear that there are some people who feel they must wear a mask every hour of every day in order to hide something they are feeling, or because of some secret they don’t want anyone else to know?”

Laura thought about the question for a minute. “No, that wouldn’t surprise me. I think I know some people like that.”

“Tha-a-at’s because you’re a very smart young woman. You also strike me as someone who naturally shows her feelings. Do you have a hard time hiding it when you’re angry or sad? Does it seem as if the whole world knows? And when you’re happy does joy burst right out of you?”

“Well, yes—I guess that’s me.”

“Of course! But you didn’t come here to listen to an old man lecture you. You came here for a Halloween mask!”

Laura giggled.“Yes! And one for my little brother, too, if he ever shows up.” She looked around nervously. What if Trevor had wandered out of the store?

“Well, certainly for a boy his age almost any costume will do.” Doctor Blaack bent over quickly, his huge goat-face bobbing up and down right in front of her. The move startled her so much she almost fell over. One of his big eyes winked. “Boys his age are so . . . indiscriminate, don’t you think?”

“I, I guess.”

“Hey! I’m not scrimin-whatever!” Trevor popped out from between two large, billowy costumes. They were supposed to be ghosts, maybe. It was hard to tell.

“Trevor! Where have you been? Don’t wander off like that!” She glanced up at Doctor Blaack. “Sorry…”

“Quite all right, my dear. I did not mean to offend his delicate sensibilities.” Doctor Blaack bowed deeply in front of Trevor. “Your pa-a-ardon, kind sir.”

“You talk funny.”

“Trevor!”

“Quite all right,” Doctor Blaack said, although his frown said something else. So, he was putting on a mask, too, she thought. “Certainly I’ve had worse things said about me. I take it you are looking for a mask, young sir?”

“A special mask,” Trevor replied. “You have something like that?”

“Well, I certainly like to believe that all the masks in my establishment are rather special. But let us see if I can find something particularly suitable for you. Some sort of ape or other subhuman creature perhaps?” Trevor frowned. “No? Perhaps not.”

Doctor Blaack turned around and began rapidly sorting through the wall of masks and costumes, murmuring to himself as he searched for a mask for Trevor. Laura turned her head and whispered to her brother, “Be nice.” Trevor just stuck out his tongue.

“Won’t do, won’t do, won’t do . . .” Doctor Blaack mumbled to himself, and eventually stopped going through the hanging merchandise and slid out some dirty, battered boxes from the dark spaces underneath. Laura wondered if he was going to look at every costume in the shop just to find something to satisfy her picky little brother—which seemed like a weird way to run a business.

Doctor Blaack stared at the dusty boxes and frowned. “Now, where did I put that very special mask?”

He poked a couple of boxes with a long, terribly skinny finger, picked several up and shook them, his ear pressed against their sides. When he took his ear away it was black with dirt. Gross! Laura thought.

Trevor giggled. “Shhhh,” Doctor Blaack said. “I’m hoping that very special mask will tell me exactly which box it is hiding in!”

“You mean it talks?” Trevor said in amazement.

“Oh, it talks, sings, even sneezes. It depends on what it needs to do at that particular moment, you see.” Without another word Doctor Blaack began pulling out more boxes and running his long fingers quickly through their contents.

Laura and Trevor ran behind another row of costumes, using them as a curtain to avoid all the flying bits and pieces, pulling them back and peeking in order to watch him work. “He looks like a big crazy bird!” Trevor said, and she didn’t bother to shush him because it was true. The room was soon so full of dust Laura’s eyes burned and she started coughing uncontrollably, but she couldn’t really see Doctor Blaack, just a flurry of movement where his arms were.

“Ah ha! I knew I’d find it!” he shouted.

The dust settled over the floor. The air began to clear. The room looked like a garbage dump, with old boxes and junky things scattered all over. And there was Doctor Blaack standing in the middle of it all, a dark shadow draped over his outstretched hands.

“You like?” he asked.

But Laura had no idea what he was holding. It didn’t look like a mask at all. It appeared to breathe in and out like some big dark living thing. Like a big black bird or maybe a bat. But she couldn’t tell. She couldn’t see eyes or nose, ears or a mouth.

The black thing floated up out of Doctor Blaack’s hands and started flapping its way toward Trevor’s face. An enormous white grin appeared in the middle of it, just like the Cheshire Cat from Alice-in-Wonderland.

Trevor yelped and ran away again, disappearing into the depths of the store. “Trevor! Come back here!” The panic in her own voice scared her even more. Soon Laura couldn’t even hear his footsteps anymore. But she understood why he ran—she wouldn’t want that thing touching her face either.

“Too baaad,” Doctor Blaack said, sounding as if he was sad but Laura was pretty sure he was just play acting. She kind of liked Doctor Blaack—he could be funny and charming—but he could also be pretty scary, and she didn’t really like it that he pretended so much. She didn’t trust people who pretended all the time—you never knew how they really felt about anything.

The black thing flew back and landed on Doctor Blaack’s hand. He stroked it and whispered something to it and put it back into its box. “It’s actually quite gentle, and would have done anything the boy asked. I suppose your little brother isn’t as indiscriminate in his choice of masks as he appears.”

“I . . .I guess not,” she replied.

Doctor Blaack stood up. He was suddenly so tall Laura had to look practically straight up. “Of course you guess!” He smiled sadly. “Do you have any idea what indiscriminatemeans my dear?”

“I don’t—not really.”

“And she’s as honest as the day is lo-o-o-o-o-ong!” Doctor Blaack shouted at the ceiling, his arms spread wide, palms up. He gazed down at her and smiled again. “In this case, it means he will wear almost anything, my dear, if you can convince him it is—what’s the word?—cool.”

“He won’t dress up like Barbie–I tried to get him to do that year before last.”

“Hmmm.” Doctor Blaack scratched his pointy little beard. “But for you, my dear, who are so clever and perceptive, and mature—you have sworn this is your lasttime trick-or-treating?”

“Absolutely.”

“Then for you, my dear, we must find something very special, something suitable for your retirement from this

perhaps too-childish activity.” He pulled a tape measure from his pocket, and leaning uncomfortably close wrapped the tape measure around her head. She was surprised, and wanted to pull away from him, but she made herself stand still. He mumbled something she couldn’t understand, pulled the measuring tape down the length of her face, and then rapidly measured the width of her head from her left ear to the right. He straightened up again, and much to her irritation patted her on top of her head. But before she could complain he turned his bony shoulders and moved away from her, pushing against the costumes hanging on both sides of him. They swung violently back and forth against her. She held up her arms to protect herself, sure she was about to be buried under a pile of Halloween disguises, but somehow they stayed on their hooks.

Doctor Blaack turned around. “Are you coming? You won’t find the right costume here among the ordinary merchandise!”

“But what about Trevor?” Laura hurried after him, but Doctor Blaack disappeared into the swaying walls of detached faces and weird bodies. She was afraid of getting lost, so she rushed forward a little faster than she should have, stumbled, and fell, sliding a couple of feet along the floor under all those hanging costumes.

With a struggle she managed to turn herself over, and found herself in complete darkness.She was terrified. She turned her head left and right and couldn’t find a glow or a glimmer or even a ghost of a light.

Then a form came rushing out of the darkness, all knees and elbows as it did its string puppet moves. As the figure drew closer, it became clear that this was Doctor Blaack. He held something in his hands.

“So what will Laura wear for her very la-ast Halloween?” he sang. “Perhaps something musical?” He thrust a mask in front of her. It was a girl’s head—her huge mouth making a silly grin, and stuck into her mouth there were seven or eight horns playing a variety of tunes. She even had a small horn jammed into each ear, and these were playing loudly, and harshly, more noise than music. And just to make the whole thing even more ridiculous two mechanical birds on loops of wire were flying around her head singing along.

“Or perhaps something chronometrical?” Doctor Blaack shouted. The musical mask disappeared, and in its place there was a girl’s head that had been turned into a cuckoo clock. Her hair looked like roof shingles and there were numbers painted on her face. Clock hands turned from a black post sticking out of the tip of her nose and her eyes crossed when the hands passed over them. Every few seconds her mouth flew open and her tongue came out, stiff as a diving board, with this goofy looking bird perched at the end. The bird would look at the oversized wristwatch strapped to its wing, and go “Coo Coo!” so loudly it made its beak wrinkle. Then it winked and the tongue slid back and the mouth shut, and the mask’s eyes closed. Then the show started all over again.

With Laura as a captive audience (Where could she go? It was so dark she couldn’t even see her feet!) Doctor Blaack demonstrated mask after mask in quick succession: a “magical” mask with a bunny hopping out of the top of the hat-shaped head, an “insect” mask made up of hundreds of flapping butterflies, an “agricultural” mask consisting of flowering plants, corn cobs, and cabbage with singing bees, and an “eggs-it-stenshul” mask whose weeping egg faces made so much sad noise she wanted to smash and scramble them to shut them up. Each was more complicated, and far stranger than the last.

“Could I . . . could I just get something a little simpler?” she asked. “More dignified?”

“Oh.” The masks all disappeared. Doctor Blaack stood before her scratching his head. “Why didn’t . . .”

“. . . you say so?” And they were back in the store again, standing in an aisle between costumes, maybe in the same spot they were before—she couldn’t tell.

She was so confused. She didn’t know how to answer him. “I don’t know. Too many choices?”

“Hmmm. Choices are a good thing, my dear, but sometimes they do require a lot of work in order to make them. But I’m sure we’ll have just the thing, given your age, hmmm…and your insistence that you are no longer a child.” He reached up and began pulling things off a shelf she hadn’t even realized was there. Several boxes dropped into his outstretched hands. He shuffled through them rapidly, tossing some of them up into the shadows, where they must have found a shelf to land on since they didn’t come back down. He was left with a single clear plastic box, which he handed to her.

It took a moment for her eyes to adjust so that she could see through the plastic into the dark insides of the box. She almost dropped it when a too-real, too-familiar face peered up at her, like the drowned face of a beautiful young woman under the surface of a sparkling pool.

“Mom?” She felt her eyes fill with tears. The face looked like her mother’s face when her mother was younger. Laura loved going through the photo albums at home, and looking at pictures of her mom and dad when they were just kids, and later in high school and college. Her mom had had such a gentle, lovely face, identical to the one in the box she was now holding.

“It’s my mother! How did you get a mask with my mother’s face on it?”

“No, my child.No—look more closely. There are differences.”

Laura held the box closer and squinted. There were some differences—the nose was a little fuller, the ears pushed out a little more from the face, the eyes—“It’s like me,” she said. “But not exactly. It’s older–”

“Exa-actly,” he said. “Perhaps this will be you when you’re a few years older. Perhaps not, who knows? Who can predict the future?”

It was a little scary, but also wonderful. “But how could you have a mask like this in your shop?”

“Trade secret. But the mask is alive. It has intelligence, of a sort. It likes to mirror people, if you will. While you were looking at it, trying to find it down in its shadowy home, it was adapting to you. Had anyone else been holding the box, that mask would look very different now. But are you pleased? That’s what’s important. And I must make my living—shall I ring it up for you?”

“Of course, yes, well—how much is it?”

“Oh, I’m sure you will have enough. Step to the back, please, to the cash register.”

Laura followed Doctor Blaack through more rows of hanging costumes, under several arches made up of fake arms and legs and tentacles and long, flowing wigs, to the big counter again. The cash register looked even larger than it had before—it was as big as the huge TV they had in the living room at home. And a beautiful old gold color with keys as big as quarters. Every time Doctor Blaack pushed one of these enormous clattering keys a metal sign the size of a playing card and shaped like a tombstone popped up inside a long glass box attached to the top of the cash register. Each of these signs had a large number printed on it, except one that displayed a decimal point. “Ten dollars, it seems,” Doctor Blaack said thoughtfully. “Do you have that much, young lady?”

That was the exact amount she’d put aside for her own costume. She eagerly reached into her jeans pocket for the money as Doctor Blaack hit another, even larger key with his fist.

A bell mounted on the wall clanged loudly as the cash drawer rolled open slowly, sounding like a train car rumbling down the tracks. “Wait!” she cried.

Doctor Blaack peered down at her, frowning. “All sales are final.”

“Oh, I still want it. I have enough money.” She pulled out a twenty dollar bill. “But I have to pay for Trevor’s too!”

“Yesssss, but where is he?”

Laura looked around. There was still no sign of her little brother. It had been a while since he’d run off—she couldn’t believe she’d forgotten that. She should have kept looking for him. “He was scared by your, well, that thing you had.”

Doctor Blaack lowered his huge face to her level. “Waass? But what about Isss?”

“Trevor? Where are you? It’s time to go!” she yelled. She looked up at Doctor Blaack. “Sorry—just let me round him up.” Laura moved quickly back under the arches and into the aisles of costumes.

Sometimes fear made you ridiculous. Sometimes fear made you imagine the worst, strangest, most impossible things: your house on fire, your family in danger, faces that looked like masks and masks that looked like faces, your brother vanished, fallen through a dark hole in the world. It was all her fault for not going after him.

“Trevor!” She’d been calling him for what seemed like ten minutes or more. She was responsible for her little brother and she had to find him.

She went down the aisle where she thought she’d last seen him. This section of the store appeared to be devoted to science-fiction costumes—there were robot costumes and all kinds of aliens—big brain heads and heads like insects, four-armed and six-armed, tentacles and claws and hands that looked like guns—and costumes based on every science fiction TV show or movie she’d ever seen or heard of. Her dad had always liked stuff like that—he said that sometimes we treat other people like they’re from an alien planet, as if there’s no way we can ever understand how they think about things, and how sad and unfortunate that was.

Trevor loved this kind of stuff too so she got her hopes up. Surely he’d want to check these out. She went up and down the aisles, shouting his name, pulling costumes apart and moving boxes around in case he was hiding, but Trevor was nowhere to be seen.

The next aisle over was movie monster costumes—Dracula and Frankenstein and guys like that. Trevor loved that kind of stuff even more, but still there was no sign of him anywhere. “Trevor! Where are you?” she shouted, but hearing her own voice all scared like that made her want to start crying, so she stopped.

“Miss! Back here!” Doctor Blaack’s face suddenly appeared at the distant end of the aisle, his clothes so black they made his body disappear so it was like his bodiless head was floating in the air. “I think he’s back in the storage room!”

Laura hurried down the aisle, following Doctor Blaack through a gray, haze-filled doorway in the back wall she hadn’t noticed before. “I don’t normally permit customers in here. It’s private,” he said sternly. “But apparently your little brother has a way of finding himself where he most assuredly does not belong.”

Should she be following this tall, scary man into a dark room like this? Stranger danger, Laura!she thought. But she had to find Trevor. Looking around the gigantic, cave-like room with all its dust and hanging cobwebs, Laura wondered why anyone would want to come back here in the first place. Doctor Blaack’s back room was a bigger mess even than his store. Boxes were piled everywhere. Broken pieces of masks and costumes crunched under her feet. Large sheets covered a lot of the stuff on the floor, as well as several tables. At first Laura thought the sheets were black, but it was only because there was so much greasy dust caked on them. Grimy boxes were stacked everywhere. The windows had been boarded up, and the only light came from a bare lightbulb overhead that had been painted red. The red light made everything look hot, as if the room were ready to burst into flames any second. And it was all so dim she could barely see the floor under her ghostly white tennis shoes. There were even more masks and costumes hanging from the ceiling and lined up against the walls like prisoners of war.

Maybe it was just all the dust (so thick on the shoulders of some of the costumes it looked like gray snow, or the world’s worst case of dandruff) and the lack of light, but it seemed to her that these costumes were a lot older than the ones Doctor Blaack displayed out on the main floor. These masks were decorated with fancy drawings and complicated patterns and faded, antique-looking colors, and the clothing that went with the masks was definitely old-timey. And some of the costumes appeared to have mechanical parts—hinged metal strips and clockwork pieces with rusty surfaces—that made them look quite old indeed.

“He’s over there,” Doctor Blaack was suddenly beside her, his arm stretched out straight and looking impossibly long, like a pole with some wiggling fingers at the end. One of the fingers pointed at a small, hunched-over figure near the wall. “Beakman discovered him.”

“Beakman?”

“My…um…assistant. He stays back here, usually doesn’t deal directly with customers.”

Laura hadn’t seen anyone else in the store—she’d just assumed Doctor Blaack ran it by himself. But she couldn’t worry over that right now. Trevor was standing by himself, hunched over with his face in his hands. It looked like he was crying, the way his back was shaking, but he wasn’t making a sound. She ran over to him, pushing past a mannequin in the middle of the floor wearing a scary-looking costume and mask—all beak and feathers and those giant eyes!—and stood next to him, putting an arm over his shoulders. “What’s wrong, honey? What happened?”

He really had her scared. She’d never called him honey before.

Trevor turned his head around. He was wearing this face mask—a cartoon mouse character. It wasn’t Mickey—it was more rat-like than Mickey, with its long pointy snout and its scared red eyes. But no, those weren’t the mouse’s eyes—those were Trevor’s eyes looking out through the mask’s eye holes. They were wet and red because Trevor had been crying. But more than that, Trevor’s eyes looked trapped inside the mask. He was terrified.

“I—can’t—get it off!” he cried in kind of a high-pitched, squeaky voice that echoed inside the pointy end.

“Oh dear,” Doctor Blaack said behind her. “I really wish he haaadn’t put thaaat one on.”