Halloween Haunts: Halloween Defines Fall, At Least for Me By John F.D. Taff

I have found, in 25 years of fiction writing now, that the surest way to a feeling of verisimilitude in a story is to process the experiences in my life and put them down on paper. I refer to this process as strip-mining my childhood, and so far, it’s been very good to me.

Not only has this practice helped me to work my way through past experiences, both good bad, it has also lent an air of reality to a lot of the scenes I have written. Write what you know is, perhaps, the oldest saw in the art of fiction, but, wow, is there anything you know as well as your own life? I think—hope!—not.

One of the most evocative things for me are the various seasons of childhood, how much more they resonate with me than as an adult of nearly 53 years. (Ugh.) There are such concrete memories, altogether different, associated with spring, summer, winter and fall. All are distinct, unique, associated with just that season. The bright, bursts of color from the profusion of things growing in spring. An ice-cold wedge of watermelon and the smell of fireworks in summer. The whisper of falling snow and the way the moon looks on a fresh blanket of it in winter.

And in fall…wow, in fall there is so much for me—the smell of burning wood in a fireplace, the heady aromas of hot cocoa, cinnamon, apples…and yes, even the ubiquitous pumpkin-pie spices, the crinkle of walking through dried leaves.

Halloween. There it is, the center of fall, at least for me. Always has been. What else is there in fall to look forward to? School? Only if you’re a parent of school-age kids, I suppose. Perhaps Thanksgiving, though that to me is an end-of-fall celebration. No, Halloween is fall to me, it embodies everything about the season, every memory of fall.

Here’s a stream of consciousness recitation of Halloween memories, with all apologies to James Joyce (sigh…you’ll see.)

The glorious anticipation of shopping for a Halloween costume. My face sweating from my trapped breath, whatever the outside temperature, trapped behind a Spider-Man or Batman mask, bought in a cardboard box from K-Mart or Venture, usually from Ben Cooper Inc.

Being forced by my mother to wear a winter coat over the costume if the temperature was below 68 degrees.

The seething anger I felt if it happened to rain on Halloween night…which it often did.

The taste of Sugar Babies or Sweet Tarts or Pixie Sticks huddled in my bed on midnight.

The huge and very communal feeling of seeing so many people, so many kids and parents, all out on that same night, all doing the same sorts of things, all having a blast. This was before there were worries about razor blades in apples or kids being snatched off the streets or LSD-imprint Casper the Friendly Ghost stamps.

The overwhelming sense of freedom, perhaps a bit more common for a child in those days, of being allowed to go out alone on this evening, to go where I wanted with few boundaries. To stay up far past my bedtime, stray beyond the boundaries of my neighborhood. And, lest we forget, the weirdly freeing wearing of a mask to hide your identity, to be someone else, something else, at least for an evening.

And, finally, the delicious little shiver of fear that this all brought about. The possibility that this truly was a holiday where weird, inexplicable, frightening things could happen, and we could actually celebrate it.

We’ve kind of gotten away from that now. Fear has become something to…well…fear. Perhaps it’s because the times truly have changed, and things (read: people) have become worse. But perhaps not. Perhaps we’ve just become a culture that likes to wrap itself in false comfort with things like Trunk or Treat (ugh) or religious-themed “haunted” houses (double ugh).

But think back to the autumns of your childhood. I bet there’s an overwhelming memory there of Halloween. One that defines fall for you. The taste of warm apple cider, perhaps. Or maybe the smell of makeup applied to your face by your mom. The feel of flannel or wool sweaters worn under your Mickey Dolenz costume.

Or just the sense of being alive, being really, really alive at ten years old during a holiday whose sole purpose, ultimately, was to remind you that sometime in your future—hopefully your far distant future–you are going to be really, really dead.

Enjoy Halloween, even if you’re an adult, because, man, that dead thing? It’s coming sooner than you might think.

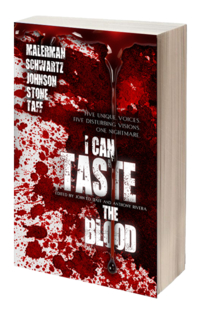

TODAY’S GIVEAWAY: John F.D. Taff is giving away two Kindle copies of his latest shared novella collection, I Can Taste the Blood. Comment below or email membership@horror.org with the subject title HH Contest Entry for a chance to win.

John F.D. Taff has been writing for about 25 years now, with more than 85 short stories and four novels in print. His collection Little Deaths was named the best horror fiction collection of 2012 by HorrorTalk. The End in All Beginnings, his collection of novellas, was published by Grey Matter Press in 2014. Jack Ketchum called it “the best novella collection I’ve read in years,” and it was a finalist for a Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in a Fiction Collection. His work has appeared recently in Dread: The Best of Grey Matter Press, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, The Beauty of Death, Cutting Block Book’s Single Slices and I Can Taste the Blood.

John F.D. Taff has been writing for about 25 years now, with more than 85 short stories and four novels in print. His collection Little Deaths was named the best horror fiction collection of 2012 by HorrorTalk. The End in All Beginnings, his collection of novellas, was published by Grey Matter Press in 2014. Jack Ketchum called it “the best novella collection I’ve read in years,” and it was a finalist for a Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in a Fiction Collection. His work has appeared recently in Dread: The Best of Grey Matter Press, Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories, The Beauty of Death, Cutting Block Book’s Single Slices and I Can Taste the Blood.

Keep up with Taff at his blog, johnfdtaff.com; follow him on Twitter @johnfdtaff, on Instagram at johnfdtaff or visit his Amazon Author Page.

I Can Taste the Blood

Five Unique Voices

From Bram Stoker Award-nominated authors Josh Malerman, the newly minted master of modern horror, and John F.D. Taff, the “King of Pain,” to the mind-bending surrealism of Erik T. Johnson, the darkly poetic prose of J. Daniel Stone and the transgressive mania of Joe Schwartz, I CAN TASTE THE BLOOD offers up five novellas from five unique authors whose work consistently expands the boundaries of conventional fiction.

Five Disturbing Visions

Five Disturbing Visions

I CAN TASTE THE BLOOD opens the doors to a movie theater of the damned; travels the dusty, sin-drenched desert with an almost Biblical mysterious stranger; recounts the phantasmagoric story of birth, death and rebirth; contracts a hit that’s not at all what it seems; and exposes the disturbing possibilities of what might be killing Smalltown, U.S.A.

One Nightmare

As diverse as they are, in voice and vision, the work of the five celebrated authors assembled in this stunning volume of terror share one common theme, one hideous and terrifying nightmare that can only be contained within the pages of I CAN TASTE THE BLOOD.

Excerpt from I Can Taste the Blood:

The night had cooled and darkened as the two old friends stumbled down the road. The skin of Norton that clung to the highway was mostly the stuff traveling people would stop for—a Casey’s General Store, a Sunoco filling station, a Dairy Queen. They passed them all, then the fire station, its sign promoting one of the town’s ubiquitous blood drives—NEXT WEEK, MAY 16-23!

Across the highway from the fire station was the Norton Grange, the town’s feed and seed store, where Gun worked for his uncle. The huge lot that stood beside it, fenced in on all sides, held farm equipment of all kinds—from tractors to irrigators, from combines to seed planters. All huge and immobile in the twilight, like dinosaur skeletons in a museum after the lights have been turned off.

And over all of it, a gigantic shadow in the background, was the town’s water tower. It was a great, cauldron-shaped thing perched atop four spindly legs, painted a weird turquoise color and emblazoned with the single word NORTON. It was at least a hundred feet tall and always reminded Merle of those Martian ships in The War of the Worlds.

He remembered reading the book long ago, when he’d been a reading kind of guy, constantly looking out his bedroom window at the water tower, as if it might suddenly lurch to life and march through town on those skinny metal legs.

Almost regretfully for Merle, it never did. Nothing interesting ever happened in Norton.

From the fire station, they turned south onto Madison Street, passed old Fern Davis’ house, Sam and Sally Deming’s place and crazy Burt Sutherland’s. Up ahead, bathed in light, was the parking lot of the VFW hall, filled with cars and SUVs, but mostly pickup trucks. The sign outside read SPAGHETTI DINNER TO-NITE! 6 P.M. to ????. BRING YOUR APPETITE!

Gun nudged him. “Mmmm…smell that? Make you hungry?”

Merle sniffed the cooling night air, and it did, indeed, make his stomach rumble. He could smell tomato sauce, cooked beef, melting cheese.

But there was also something else, something that seemed, well, off a little.

Merle shook his head, trying to clear it, and pushed after his friend.

* * *

Inside, the place was packed with people lined up to pay their admissions and get their meals. Eight dollars bought unlimited spaghetti—with vegetarian sauce, meat sauce or meatballs—an Italian salad and plenty of cheese garlic bread. Lemonade, tea—sweet and unsweet—soda, coffee and, of course, beer.

They knew everyone in line, everyone at the little desk where people took their money, everyone behind the counter who ladled out the spaghetti, dished out the limp salad with steel tongs, shoved a couple of hunks of bread, redolent of garlic, onto their piled plates. He went with Gun to the table where there were urns of coffee and pitchers of tea and lemonade, followed his friend’s lead in filling a Styrofoam cup with coffee the color and consistency of motor oil.

They waded through the crowd in the low, drop-ceilinged dining room of the VFW hall, nodding to this person, shaking a hand or two, bestowing kisses on the dusty, rose-scented cheeks of a few women who were their mothers’ contemporaries. Taking a seat at one of the rows of communal tables that filled the room, Merle set his plate before him, put the paper napkin on his lap, bowed his head and pretended to say a few silent words.

When a suitable period had passed he looked over at Gun seated next to him. The man’s lips moved, and Merle instantly felt both impressed that his friend really did seem to be saying pre-meal grace and somewhat ashamed that he hadn’t. He watched Gun finish his prayer, then pick up fork and knife and dive into his plate of food.

Merle, however, didn’t feel right, didn’t feel good. Instead of eating, he looked around the room. It was packed with people of all ages, each hunched over plates, shoveling food into their mouths. The room was dense with noise—voices chattering, children laughing, people slurping spaghetti, drinking, crunching bread. There was the sound of chairs scooting in and out from beneath tables across the scuffed linoleum floor. The squeaky sound of plastic knifes slicing across Styrofoam plates.

And chewing, chewing, chewing.

He absently scratched between the fingers of one hand, then the other.

“You gonna eat or what, man?” Gun asked.

Still rubbing his fingers, Merle looked down at his plate.

The food before him glistened under the jaundiced, yellow light of the fluorescents, shone as if it were covered with a layer of slime. Even the garlic bread shimmered as if sweating. The salad looked like greasy pieces of green construction paper heaped together with stringy strands of celery and red clots of pimento.

Merle’s stomach began to feel distinctly unwell.

Then, as he watched in amazement, the noodles on his plate moved, undulated like a mass of thin, pallid worms. The whole mound of his spaghetti heaved atop his plate, seemed to wind in upon itself.

And the sauce, the red sauce, began to look distinctly watery, distinctly biological, like blood and serum that had separated. He could see it bead on the bone-colored surface of each strand of pasta, like wax on the body of a freshly washed car.

Merle’s stomach folded inside him. His hands, still itching, went below the lip of the table and grabbed his gut, pushed in a little in an attempt to settle it.

But it got worse when he raised his eyes from the table.

He looked out over the crowd again, and now most of them weren’t people. They were monstrosities, horrors, deformed and twisted, hardly human.

Verrill McKay, one of the town’s biggest farmers, sat there large as life, a head atop a melting, squiggling mass of congealed flesh that brought to mind a Jell-O mold left too long in the sun, collapsing like a landslide over his chair. Merle could see inside the pinkish, opaque gel—dark internal organs and some things that might have been his bones, strangely limp and pliable. Other things, too, things that pooled in the center of Verrill’s body, where a stomach might be—a writhing mass that might have been the spaghetti and the curled body of what was, without a doubt, a cat.

A housecat.

Merle began to sweat extravagantly, and his mouth filled with saliva. Not because he was hungry, far from it. It was a familiar feeling though: the presage of vomit.

He swallowed, turned.

There was old Bernice Johnson, her skull tiny, shrunken atop her Sears housedress-clad body. A dozen or so tiny, glittering eyes ringed her head. Her arms—now a bouquet of spider limbs, each barbed with sharp, black hairs, each crooked the wrong way—palped the table before her.

Over there was Janey Richardson, a woman a few years younger than Merle whom he’d had a brief but torrid affair with a while back. Her head sat atop a sea of writhing pseudopods, like an enormous, upturned jellyfish. Thin, ghostly arms threaded through the crowd of people, each latching onto a person with a nasty, many-toothed little mouth, like a lamprey’s. Through their spindly, mostly transparent coils, he could see a dark, pulsing inner core of liquid sucked from these seemingly unaware people, traveling back toward Janey’s body.

She turned to him and her mouth was filled with black ichor that stained her lips, tongue and teeth. Her smile was an oily arch in her face.

His stomach lurched.

Finally, over in the corner, he caught the eyes of a young boy, Caleb Morris, one of Mike and Vanessa Morris’ sons. The tow-headed, freckle-faced kid slurped in a single strand of spaghetti and smiled at Merle.

Then with no warning, the kid’s head split in two, vertically. Not ripped, but split cleanly along what looked to be a natural line of bifurcation that ran from the center of his hairline, down his nose, across his lips and mouth and ending at his chin. Merle could hear the wet, smacking sound of Caleb’s head parting, like two moist lips, even above the din of everyone eating. An obscenely thick, obscenely moist red tongue curled upward from this dark maw.

Merle watched, stunned, as Caleb lifted his sagging plate and upended it—noodles, salad, bread and all—and dumped it into this ever-widening mouth. The tongue caught each morsel, slurped them noisily down, and the two sides of the kid’s face closed and opened, closed and opened, chewing.

Merle pushed back from the table, stumbled to his feet.

Caleb’s eyes had turned a bright orange, slit vertically like a cat’s, and they rolled in their orbits, following Merle as he lurched down the aisle between the tables and toward the restrooms.

Merle saw one of those eyes wink at him, then the black crevasse in the kid’s face closed slowly, sealing itself without a trace.

He heard Gun call after him as he pushed the restroom door open, skidded into an empty stall and fell to his knees. What he vomited up, he had no idea. He had no clear recollection of eating that day, but whatever it was came up all the same.

His throbbing, sweating head touched the cool porcelain, and he looked down at the water in the toilet. Thick white curds and mucilaginous strands of slime swirled there in the rust-stained bowl. Seeing them made him heave up another mouthful, but what he brought up didn’t seem like vomit.

It wasn’t rank or acidic or filled with bile. It was smooth and thick and smelled vaguely of bread dough and mildewed towels.

He hung there for a while until he heard the door open.

“Merle? Buddy? You okay in here?”

Gun.

Merle got to his knees as another wave of nausea hit him.

What the shit’s wrong with me?

What the shit did I see out there?

And what the shit was on my plate?

The door to his stall squeaked opened and a shadow fell over him.

He felt hands slide under his armpits, haul him slowly to his feet.

He turned to face his friend.

“Jesus, man. What the fuck’s the matter? How much you had to drink today?” Gun whispered, grabbing at some toilet paper, balling it up and swabbing Merle’s face with it.

Merle didn’t answer. Any attempt to talk, to contemplate an answer, to think of what had gone on out there in the dining room of the VFW hall made him distinctly nauseous. So he shrugged, let his friend help him from the restroom.

He heard laugher on the way out of the building. A few people offered to help Gun get him home. Scotty Doorman helped Gun carry him outside to his truck.

Before the front doors of the VFW hall closed, Merle looked back into the dining room.

Everyone had gone back to eating and talking as if nothing had happened.

Everyone—Verrill, Bernice, Janey, even little Caleb—all seemed normal, all paid him no mind.

He remembered falling near Scotty’s truck and his two friends lifting him, sliding him into the back of the Crew Cab where his cheek touched the cool vinyl seat and made him feel better.

He saw the dark outline of the water tower etched against the evening sky, blotting out the stars, and then he was out, too.

Yes! to so many of these. Wearing a coat over a costume, rain on halloween, both of the worst evils. And it felt fantastic wandering around the neighborhood on a dark evening (I was always so surprised when, after having been gone for what felt like 5 hours, it was only 2)

And I have tasted the blood, and I don’t need to win (if for some reason I must be picked, I’ll pass it along to another. Or if it gets here fast enough, to some lucky reader who knocks at my door halloween night)